Watching “Manolo: The Boy Who Made Shoes for Lizards” is akin to skimming a celebrity-saturated Instagram page. There are plentiful pretty faces and objects on display, but nary a trace of substance in the captions and no link in the bio. The best thing about the picture is the title, which suggests a more imaginative and revealing profile of its titular subject, a man widely deemed as the world’s greatest living shoemaker. I went into the screening knowing virtually nothing about Manolo Blahnik, and left knowing next-to-nothing. First-time director Michael Roberts assembles a high-profile crowd of acquaintances and admirers—some of whom only materialize via voice-over—and has them drone on and on about what a legend Blahnik is. Perhaps die-hard fashionistas would find this reasonably diverting, but to everyone else, it is guaranteed to grow tiresome very quickly.

Let’s start with the lizards’ custom-fitted shoes, since the film does as well. We hear Blahnik reminisce about crafting tiny footwear for the critters while growing up in Santa Cruz. This is depicted in black-and-white recreations, and then the sequence ends, registering as little more than an attention-grabbing prologue. What compelled him to make shoes for the lizards and what significance does this have to his legacy in general, apart from being a quirky diversion? It’s not long before we realize that the film is interested solely in such diversions, while tap-dancing around the complexities of Blahnik himself. Only in its final third does the movie offer some glimmers of dimension, as the designer touches upon how he never sought out a relationship, has a severe case of germophobia and annually attempts to forget his birthday.

He has no political beliefs or life partners to speak of, and though sex clearly fuels his imagination, he doesn’t consider himself a “sexual being.” Since Blahnik finds fulfillment first and foremost through the act of artistic creation, the film should’ve delved into the particulars of his process, but it never strays from its surface-level perspective. For all the blathering that takes place onscreen, the film is awfully inarticulate when it comes to its own topic. We don’t even learn the names of Blahnik’s signature shoe designs until they’re rattled off on title cards toward the end. Left unexplained are the reasons for why and how the designer’s shoes are so comfortable, earning him a devoted global fan base that includes Rihanna and Vogue editor Anna Wintour.

Instead, the audience is treated to the cinematic equivalent of a slapped-together PowerPoint presentation, as Roberts lists the bullet points of Blahnik’s past without bothering to connect them. Here are a collection of newspaper headlines detailing his rise to the top. Here are three fashion icons he knew who have died. Here’s footage from the designer’s favorite movie, Luchino Visconti’s “The Leopard.” Golly gee, Princess Diana is wearing a pair of Manolo stilettos! And isn’t that Donald Trump among the crowd at one of Blahnik’s shows? It’s easy to get distracted by the little details when the film’s narrative is utterly devoid of conflict. Roberts breezes over Blahnik’s childhood, portraying it as a big happy bore, without detailing the influence of his mother—not to mention a trunkful of Pietro Yanturni shoes—on the man’s work.

Even when fashion became schizophrenic in the ’90s, Blahnik’s popularity was resilient, as illustrated by a clip from “Sex and the City,” where Carrie’s Manolos are stolen at gunpoint. When the film pauses long enough to offer nuggets of insight, they are often inconsistent. Blahnik’s longtime friend, Rupert Everett, quips that the designer’s shoes for men are actually more feminine versions of his women’s shoes, but later praises the dominating masculinity of certain designs, comparing them to a giant phallus. Blahnik is renowned for his warm disposition while dealing with customers, yet model Penelope Tree recalls how he chastised her for having the feet of a peasant.

Though the film seems to find its banter between Blahnik and his fawning admirers amusing, I only remember laughing once during the picture. During his first big collection show in the early ’70s, Blahnik had forgotten to insert steel into the rubber high heels worn by his models, causing them to stumble lopsidedly down the runway. The disastrous footage is quite enjoyable in part because of the models’ good-natured spirit, cavorting in the spotlight rather than sulking away in shame. Their refusal to take themselves seriously certainly mirrors that of Blahnik, whose penchant for mugging is charming at first, yet also prevents him from having an unguarded moment on camera.

The deeper problem is the director’s tendency to punctuate nearly every scene with a flippant tone, even when the subject matter is no laughing matter. In an audio interview, Sofia Coppola reflects on how her exuberantly unconventional 2006 period piece, “Marie Antoinette,” dressed the 18th century queen in Manolo shoes, allowing the Oscar-winning costume designs of Milena Canonero to be as modern as the post-punk soundtrack. Coppola viewed Antoinette as a trophy wife resigned to losing herself in shopping as a method to avoid her loveless marriage. The poignance of this observation, hinting at a deeper reason for why people make extravagant purchases, is instantly upended once a cartoon of Antoinette’s decapitated head bounces comically off the screen.

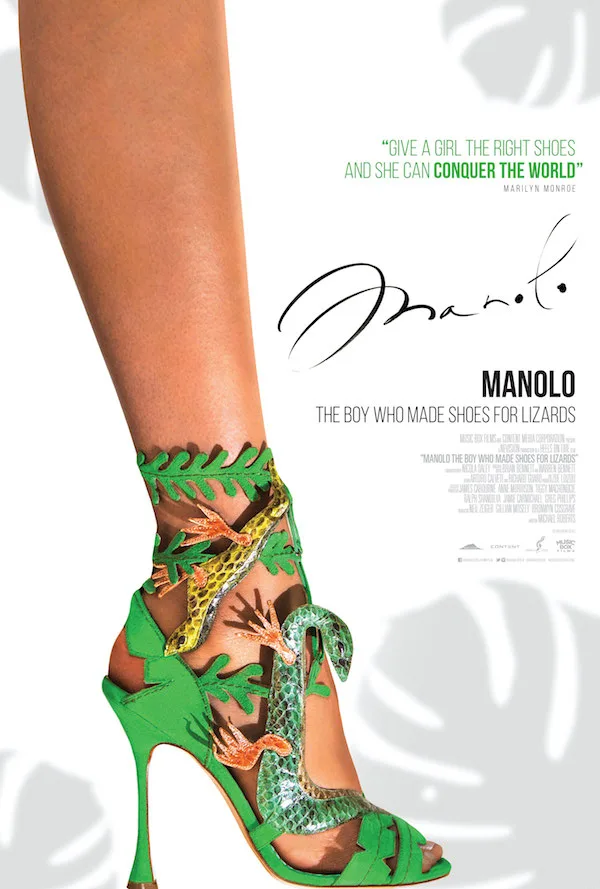

All one has to do is glance at the fetishistic close-ups of Blahnik’s shoes to know that there’s bound to be an interesting film that could be made about his life. A childlike playfulness exudes from every curlicue and plume of color adorning his designs. It’s easy to see how he was influenced by the photography of Cecil Beaton in how it fused disparate elements in visionary ways. How unfortunate that this picture spends most its time, to paraphrase Beaton, “cooing like a bloody dove” at its own subject. Roberts appears less interested in exploring Blahnik’s life than in being him. The overbearing score utilizes Tchiakovsky’s immortal “Sugarplum Fairy” theme not once but twice in order to illustrate the designer’s sprite-like nature, as he frolics from one subject to the next with unerring glee. Alas, the film follows in its subject’s footsteps to a fault, and it does so in rubber heels.