The man in the apartment down the hallway is so awfully nice. He has one of those deep, expansive voices, and a face that breaks naturally into a smile, and the kind of big, disorganized body that’s somehow reassuring. Therefore, obviously, he must be hiding something. And when his wife dies of a heart attack, it cannot be as simple as that. There must be more to it. Something deep, dark and ominous.

This is the way Carol’s mind works. She can’t help it; she was probably raised on Nancy Drew. She drives her husband nuts. He wants her to shut up and go to sleep, but all night and all day her mind is at work, threading together facts and possibilities into an obsessive theory: This nice guy has killed his wife, and unless she does something about it, he’ll get away with murder.

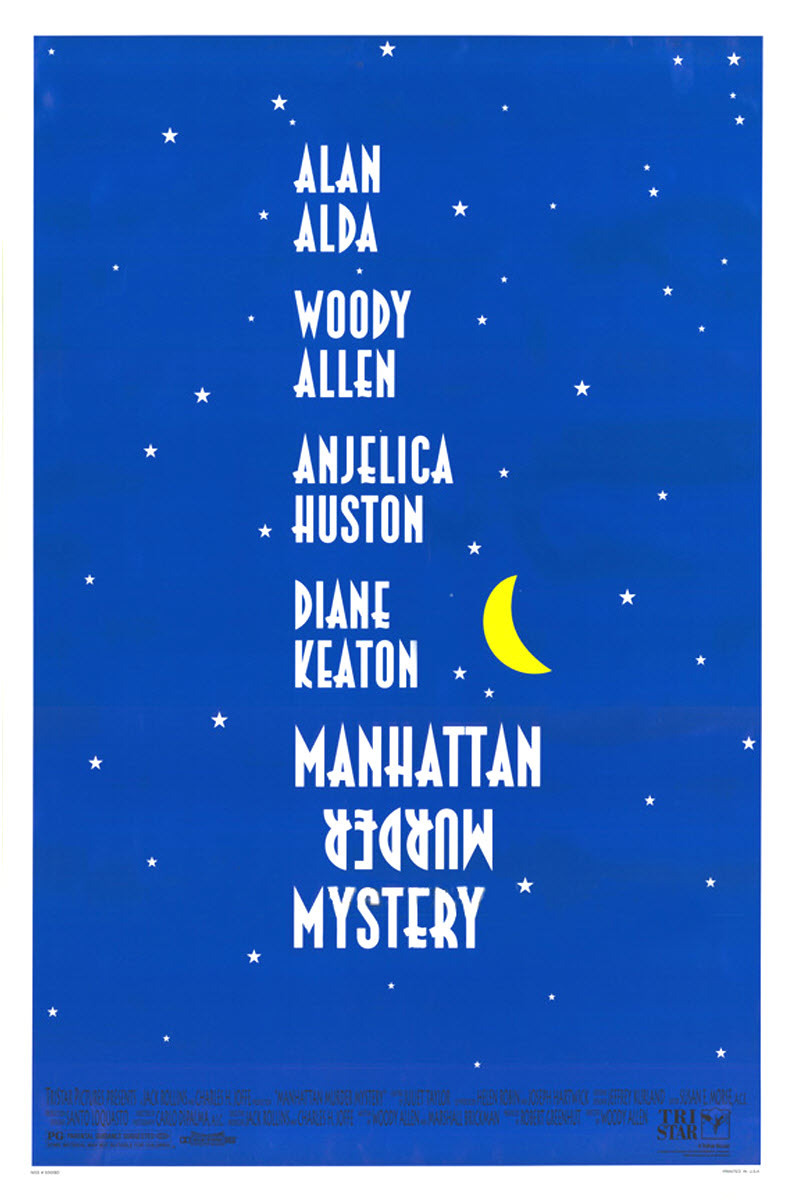

This is the kind of plot you might expect on “Murder, She Wrote.” In the hands of Woody Allen, in his new comedy, “Manhattan Murder Mystery,” what happens is more or less what would happen in a 1930s novel about an amateur detective.

But how it happens is more or less the way it would happen in one of the “Thin Man” comedies, where Manhattanites are stacked side by side in luxury apartment buildings where the walls are just thin enough to arouse suspicions, but too thick to permit proof.

The movie stars Diane Keaton as Carol Lipton, who can put two and two together working with one two. Woody Allen plays her husband, Larry, who believes that God created neighbors to mind their own business and man should leave it that way. The neighbor, the friendly, avuncular Mr. House, is played by Jerry Adler. One day he and his wife run into the Liptons in the hallway, and a conversation leads to an invitation to drinks. There’s a warm conversation about the joys of many years of wedded bliss. The next day, Mrs. House is being carried out of her apartment feet first. Heart failure.

But that’s funny, Carol Lipton frets. Mrs. House didn’t say anything about heart problems. Larry tells her to mind her own business. She can’t. She shadows Mr. House to a movie theater, and sees him in deep conversation with a young “model type.” They’re talking money. Obviously, this guy murdered his wife and is going to run off with his bit of fluff on the side.

The plot of “Manhattan Murder Mystery” proceeds as if Carol not only read the Nancy Drew books, but studied them for spycraft.

She sneaks into the House’s apartment, in a scene that’s structured for suspense because she might be caught there. I knew it was contrived, and that’s why I liked it; Allen is playing here with the conventions of the genre, with the delicious danger of being caught flatfooted inside someone else’s apartment with no alibi. The Keaton character has the courage and recklessness of the innocent. She even hides under the bed.

Both Allen and Keaton are playing clones of the characters they played in “Annie Hall.” This could be, in a way, the same couple, 15 years down the road, still caught in the paradox of her energy and daring, and his neurotic timidity.

Their dialogue is pure Allen, and elevates the material to a sort of ironic commentary on itself. Some of the lines will become as famous as the spider as big as a Buick. This one, for example: “There’s nothing wrong with her that a little Prozac and a big polo mallet wouldn’t cure.” Or Allen trying to put his foot down as the man of the household, when she stays up all night sorting out her theories: “I’m your husband; I’m commanding you to sleep. Sleep! I command it. I command it. Sleep! I forbid you to go. I’m forbidding.” She leaves. “Is that what you do when I forbid you?” The would-be investigation broadens from comedy into farce when the couple enlists the help of friends (Alan Alda and Anjelica Huston). The Huston character, the well-named Marcia Fox, is afire with theories and strategies, and is a keen egger-on. Alda plays the best-buddy character, a fixture in many of Allen’s films, and gets involved despite his qualms. The climax would make Miss Marple proud.

Allen has been called a filmmaker whose subject is Manhattan first and the world second, if at all, and certainly the situation in “Manhattan Murder Mystery” is one that any high-rise apartment dweller (like Allen himself) will naturally identify with. People who live closely together are likely to find out more about each other than they really ought to know. Sometimes there is even a sort of conspiracy of silence, in which neighbors know their secrets are mutual, and so both sides affect to notice nothing. To actually notice – worse, to pry – is a violation of the code, and it is that violation that seems to disturb the Allen character even more than possible danger. A similar situation was exploited in Allen’s “Another Woman,” the film where Gena Rowlands unexpectedly began to hear the secrets of strangers through the air shaft.

“Manhattan Murder Mystery” is an accomplished balancing act.

It is, on one level, a recycling of ancient crime formulas about nosy neighbors. On another, it’s about living in the big city. On still another, it’s about behavior and tabus and breaking the rules. And always with Woody fretfully convinced that it would be safer for everybody if they just stayed at home and pretended there were no neighbors; that the world was inhabited by one fearful neurotic and his crazy wife, who thankfully, therefore, didn’t have anyone to practice on.