Arthur Hiller’s “Making Love” tells the story of a couple that has been married for eight years happily married, according to the evidence when the husband has an affair with another man, discovers that he is gay, and decides to leave his wife. “Making Love” is limited primarily to the characters’ sexual identities. There would be no movie if the husband were not homosexual; this film has nothing else to be about. Its characters, as written, aren’t open to the surprises of real life, because the movie is single-mindedly about the specific nature of their sexual dilemma.

Since we already know the secrets when we start watching “Making Love” (the ads summarized the plot), we feel locked in; there’s nothing to do but wait while the movie marches through its lockstep development. The stages are predictable: (a) introduction of the ideal marriage; (b) the husband’s secret homosexual desires; (c) the other man; (d) passion and deception; (e) the revelation scene; (f) unhappiness and acceptance; followed by (g) a brave new tomorrow.

Every scene and almost every line seems to be programmed to make an obvious point. This movie has some of the worst dialogue one can imagine: She:”What about passions?” He: “What about supports?” She: “What about betrayal?”

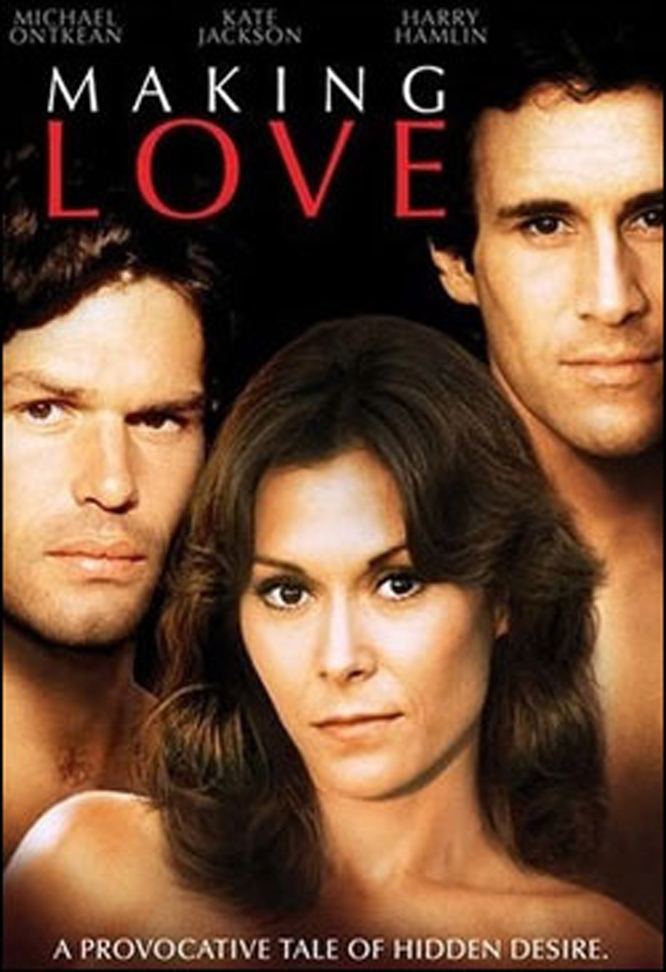

The movie stars Kate Jackson as the wife, Michael Ontkean as her husband, and Harry Hamlin as the homosexual writer Ontkean falls in love with. Jackson’s a TV executive, Ontkean’s a young doctor, and their marriage (pre-Hamlin) exists in one of those Hollywood wonderlands in which young couples figure they can meet the mortgage payments if they start brown-bagging their lunch. No attempt is made to present the marriage in messy human terms; it has to be boringly happy so that Jackson can be amazed when her husband walks out.

And walk out Ontkean does, after some preliminary false starts. He visits a couple of gay bars populated exclusively by extras who look as if they should be posing for an “Ah! Men!” catalog. He drives down an alley lined with shoulder-to-shoulder hustlers. Then Hamlin comes into his office for a physical exam (the most cursory and incompetent such exam, incidentally, ever presented in a movie). Ontkean is attracted, asks him out to dinner, and the rest is predictable, right down to the obligatory scene in which Jackson tears her husband’s clothes out of the closet and throws them on the floor.

“Making Love” is essentially a TV docudrama, in which the subject is announced loud and clear at the outset and there are no surprises. People have described the movie to me in one sentence as “Kate Jackson finds out her husband is a homosexual,” and they haven’t left out much.