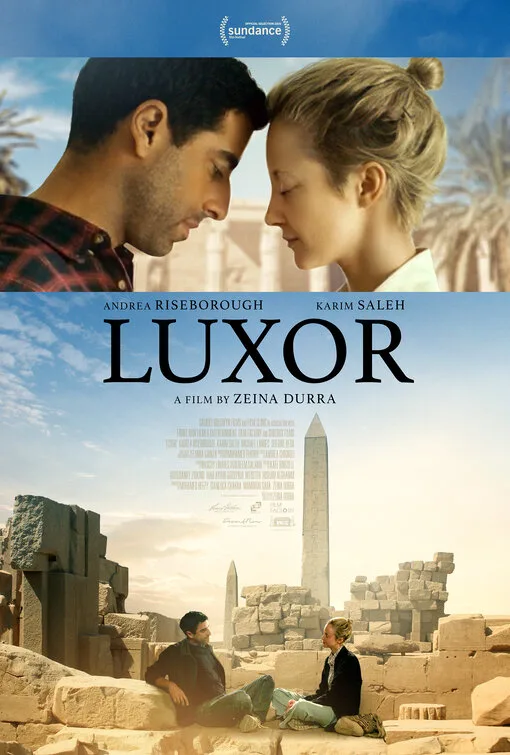

There is a certain individualized insignificance that arises as a response to the tremendousness of history. A place defined by the past can feel frozen by accomplishments, decisions, and disappointments from years before. Compared with that much weight, does anything we do matter? Filmmaker Zeina Durra’s entrancing, languorous “Luxor” wonders about the allure of the backward gaze and the uncertainty inspired by an unknowable future, and co-stars Andrea Riseborough and Karim Saleh are practically perfect in this thoughtful romance.

A decade ago, Durra’s “The Imperialists Are Still Alive!” imagined the experiences of an Arab woman living in Manhattan after Sept. 11, 2001. Durra’s own ethnic background (with a mother who is Bosnian-Palestinian and a father who is Jordanian-Lebanese) informed the film’s questions about expat activism, artistic creativity, and what we owe the cultures that birthed us. “It’s not about religion, it’s about resistance,” that film’s protagonist told her lover as a way to explain her conspiracy theories about anti-Middle Eastern sentiment. “The Imperialists Are Still Alive!” was ultimately an assertion of identity in a New York City sliding rapidly toward xenophobia.

“Luxor,” meanwhile, is a 180-degree rotation, focusing instead on a white British woman returning to Luxor, Egypt, after nearly two decades away. The film is as inclusive as “The Imperialists Are Still Alive!” in its demonstration of various perspectives from the members of one ethnic group, but its confidence and pride are quieter. Surgeon Hana (Andrea Riseborough, giving another still-waters-run-deep performance this year after “Possessor Uncut”), traumatized by her time working in yet another war zone, this time along the Jordan/Syria border, books a room for herself at the colonial-era Winter Palace, a fading hotel straight out of a Wes Anderson film. At night, she drinks by herself at the hotel bar, while by day, she wanders around Luxor, reliving old memories. Hana is quiet, and she keeps to herself, and she is in Luxor, amid the carved columns and the painted tombs, to get lost—to forget the horrors that she has accumulated over so many years attempting, and failing, to save lives.

While on the ferry traveling from one side of the Nile to the other, Hana is spotted by a familiar face: Her ex-lover Sultan (Karim Saleh) is charming and friendly, his warmth puncturing the veil of solitude with which Hana had wrapped herself. As the two begin spending time with each other, reconnecting after a failed long-distance relationship in their 20s, something within Hana begins to shift. Is it an acceptance of her missteps? A reconciliation of her laments? The city of Luxor provides integral context for Hana’s reconsideration of herself and of paths not taken, and the world Durra builds is one in which the bravery it takes to start again might be too much.

The pace is languid and introspective, and Durra’s script methodically invites us into various pockets of intimacy. Mustard-yellow intertitles divide the film into chapters based on locations in Luxor: the Winter Palace and its magnificent garden; the tomb of Setti I in the Valley of the Kings; a wisewoman’s home in the desert, hidden away from the tourist traps. The ancient city—once a thriving hub after the unification of Egypt four thousand years ago—now operates as a sort of open-air museum, and Durra frames each corner of it to show the resilience of its people and the beauty of this place. Taxi drivers, who know every inch of these dusty roads and ancient landmarks and who recognize patrons they haven’t seen in 20 years. Tour guides who easily switch between Arabic, English, and Mandarin, providing their clients with whatever version of Luxor they want to see. Bartenders who indulge the most obnoxious of guests, letting the millionth terrible joke about Agatha Christie slide by. Archeologists who prioritize archiving and protecting the integrity of the past, and who continue their research even after their grant funding runs out. Luxor is many cities at the same time, and Durra honors its multifaceted nature by paying as much attention to the graffitied portraits of Horus and Isis lining Luxor’s streets as it does to the posh resorts that employ the very locals who might have painted those images.

That distinct sense of place is essential to “Luxor” because so much of who Hana and Sultan are, both individually and together, is tied up in it. Hana’s drive to the Winter Palace is a glimpse into Egypt’s unique miasma: the sound of the Nile, splashing up against the banks, contrasted with the tinny buzz of motorbike engines; a horse and carriage pass by Hana’s car, then a speeding ambulance; the sunlight illuminates Hana’s face, stoic in her no-nonsense bun and blandly oversized outfit. Nothing seems to be affecting Hana very much until she asks her driver to pull over at an excavation site; how Riseborough seems to come alive while watching the unearthing of developments long forgotten mirrors the transformation Hana herself will undergo. “I don’t remember much these days,” she says, but whatever compartmentalization she’s used to get through the rigors of working in a warzone begin to fall away when she reconnects with Sultan.

Riseborough and Saleh (working with Durra again after “The Imperialists Are Still Alive!”) have excellent, lived-in chemistry, and their slow dance around each other, the conversations inundated with references to their shared past, bring to mind Richard Linklater’s “Before” trilogy and its complicated consideration of modern love. During a carefree traipse around the Winter Palace’s staff-only wing, acting out the people they were 20 years ago, Hana and Sultan make perfect sense together. Once the performance ends, though, they’re still 40somethings with very different jobs, personalities, and lives, and their breakup still stings. The film’s funniest moment is Hana’s shock that she’s friends with Sultan on Facebook, but the altercation immediately tumbles into bitterness. “The last thing I want to see is you happy on a beach in Dubai with kids,” Riseborough says, and the direct vitriol of that line hints at whatever tore the couple apart in the first place.

“Do you ever worry about opening up places that have been laid to rest?” Hana asks Sultan; “I don’t think we knew what time was when we were young,” Sultan says later on. “Luxor,” with hints of mysticism and sensuality, navigates the space between our regret of past mistakes and our fear of future ones, and the empathy it provides to both lingers.

Now available on demand and on digital platforms.