Why does the United States so often back the reactionary side in international disputes? Why do we fight against liberation movements, and in favor of puppets who make things comfy for multinational corporations? Having built a great democracy, why are we fearful of democracy elsewhere? Such thoughts occurred as I watched “Lumumba,” the story of how the United States conspired to bring about the death of the Congo’s democratically elected Patrice Lumumba–and to sponsor in his place Joseph Mobotu, a dictator, murderer and thief who continued for nearly four decades to enjoy American sponsorship.

Pondering the histories of the Congo and other troubled lands of recent decades, we’re tempted to wonder if the world might not better reflect our ideals if we had not intervened in those countries. American foreign policy has consistently reflected not American ideals but American investment interests, and you can see that today in the rush toward Bush’s insane missile shield. There is little evidence it will work, it will be obsolete even if it does, and yet as the largest peacetime public works project in American history is it a gold mine for the defense industries and their friends and investors.

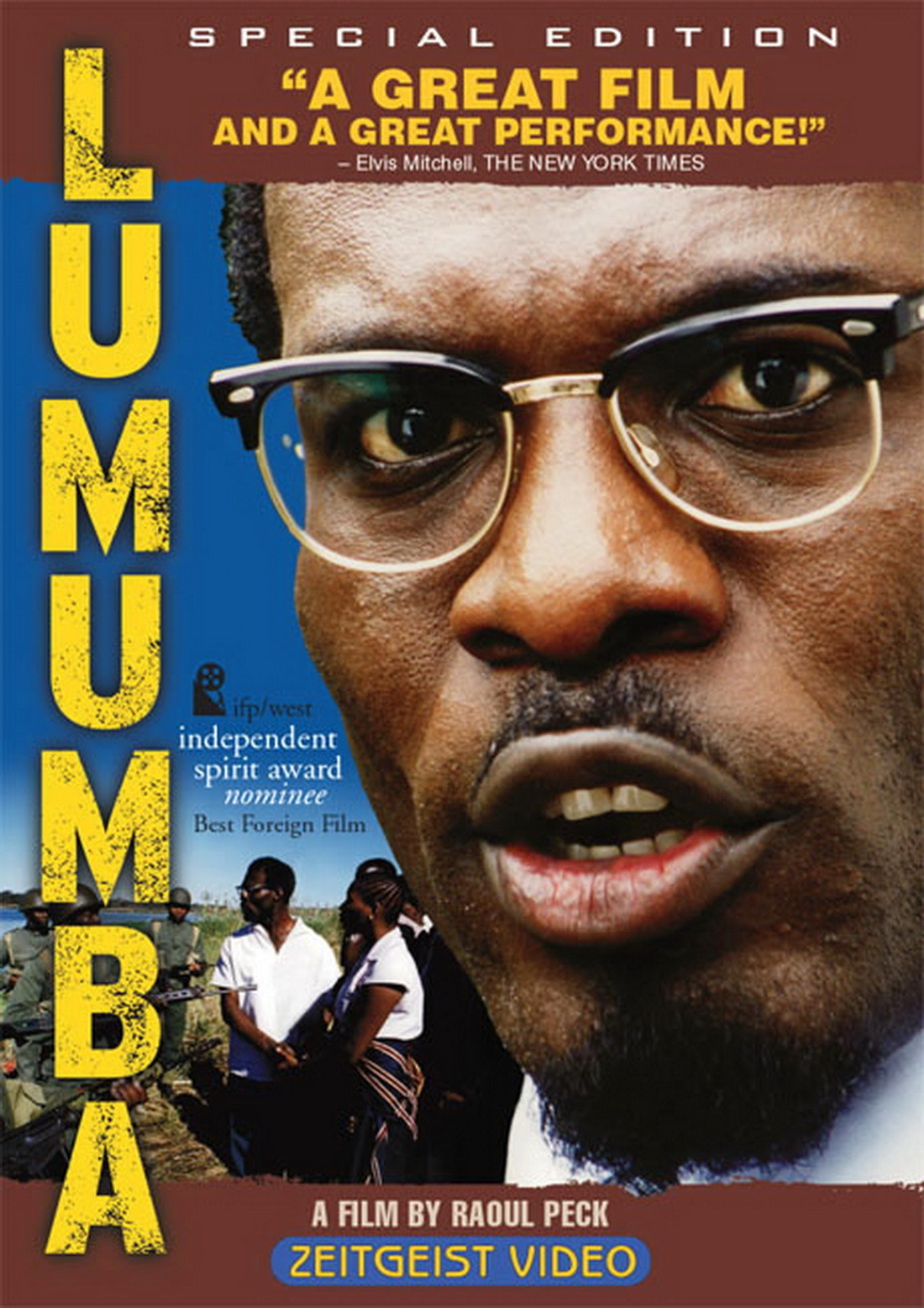

Patrice Lumumba is a footnote to this larger story. Raoul Peck’s film (a feature, not a documentary) begins with his assassinated body being dug up by Belgian soldiers so it can be hacked into smaller pieces and burned in oil drums. Lumumba’s disfigured corpse begins the narration that runs through the film. He recalls his early days as a beer salesman, a trade that helps him develop a talent for speaking and leadership. As it happens, the beer he promotes has a rival owned by Joseph Kasa Vubu–who later becomes president while Lumumba is named prime minister and defense minister. It is Kasa Vubu who eventually orders the arrest that leads to Lumumba’s murder.

In the 1950s, Lumumba becomes a leader of the Congolese National Movement. His abilities are spotted early by the Belgians, who after a century of inhuman despoliation of a once-prosperous land, are fearful of powerful Africans. Lumumba is jailed, beaten, and then released to fly to Brussels for the conference granting the Congo its freedom. He takes office to find the armed forces still commanded by the white officers who tortured him, and when he tries to replace one of the most evil, he is targeted by the CIA, the Belgians and the resident whites as a dangerous man, and his fate is sealed.

Most of the natural riches in the Congo are concentrated in the Katanga province, which declared independence from the mother country, in a coup masterminded by the West. Lumumba’s attempts to put down this rebellion got him tagged as a communist, particularly when he considered asking the Russians to support the central government. Well, of course the opportunistic Russians would have been glad to oblige–but why did a democratic leader need help from the Russians to protect himself from the Western democracies? The movie re-creates scenes that will be familiar, from another angle, to readers of Barbara Kingsolver’s great novel The Poisonwood Bible , which tells the story of an American missionary family that finds itself in the Congo at about the same time. Jailed by Kasa Vubu, Lumumba escapes and tries to flee with his family to a safe haven, but is captured and shot by a firing squad, without a trial.

We do not learn much about Lumumba the man. Eriq Ebouaney, a French actor whose family is from Cameroon, plays Lumumba as a stubborn, fiery leader, good at speeches, but unskilled at strategy and diplomacy. Time and again, we see him making decisions that may be right but are dangerous to him personally. Although the narration is addressed to his wife, we learn little about her, his family or his personal life; he is used primarily as a guide through the milestones of the Congo’s brief two-month experiment with democracy.

Writer-director Peck has a long-standing interest in Lumumba and made a documentary about him in 1991. He is a Haitian by birth, a onetime cultural minister there, and so knows firsthand how despotic regimes find sponsorship from Western capital. His film is strong, bloody and sad. He does not editorialize about Mobutu, except in one montage of shattering power. On his throne, guarded by soldiers with machine guns, Mobutu gives a speech on his country’s second Independence Day. Mobutu asks for a moment of silence in Lumumba’s memory, and as the moment begins, Peck cuts away to show the execution, burial, disinterment, dismemberment and burning of Lumumba–and then back again to Mobuto’s throne as the moment of silence ends.