“Lucie Aubrac” is set in Lyon in 1943 and tells the story of a brave, pregnant woman who leads a daring raid to free her husband, a Resistance leader who has been condemned to death by the Gestapo. It is based on a novel by the real Lucie Aubrac, who says in a final screen note that she chose Claude Berri to direct the film because of his support for a foundation that commemorates the Resistance. It is a quiet and bitter joke in France, of course, that once the war was over, everyone turned out to have been in the Resistance; the Nazis ran things with no help at all.

The opening titles tell us that “Lucie Aubrac” is based on fact, although “certain liberties” have been taken for the purposes of drama. On a whim, I searched for Raymond and Lucie Aubrac on the Web, and turned up many pages from Liberation, the Paris daily, involving a controversy over the most basic facts of all. Were the Aubracs indeed Resistance heroes as Aubrac’s novel presents them, or did Raymond crack under Gestapo torture and identify the Resistance leader Jean Moulin? Detractors point to the coincidence that soon after Raymond’s escape, Moulin was betrayed.

I don’t have a clue about these facts, any of them. I doubt Lucie Aubrac would draw the attention of a novel and film to her story if she felt it could be disproved. At this point the Gestapo witnesses involved are certainly dead (among them Klaus Barbie, the “Butcher of Lyon,” who makes a brief appearance here). What we are left with is a story that, if true, is certainly heroic. But since we are attending a movie and not a benefit, we must ask if we are moved and entertained.

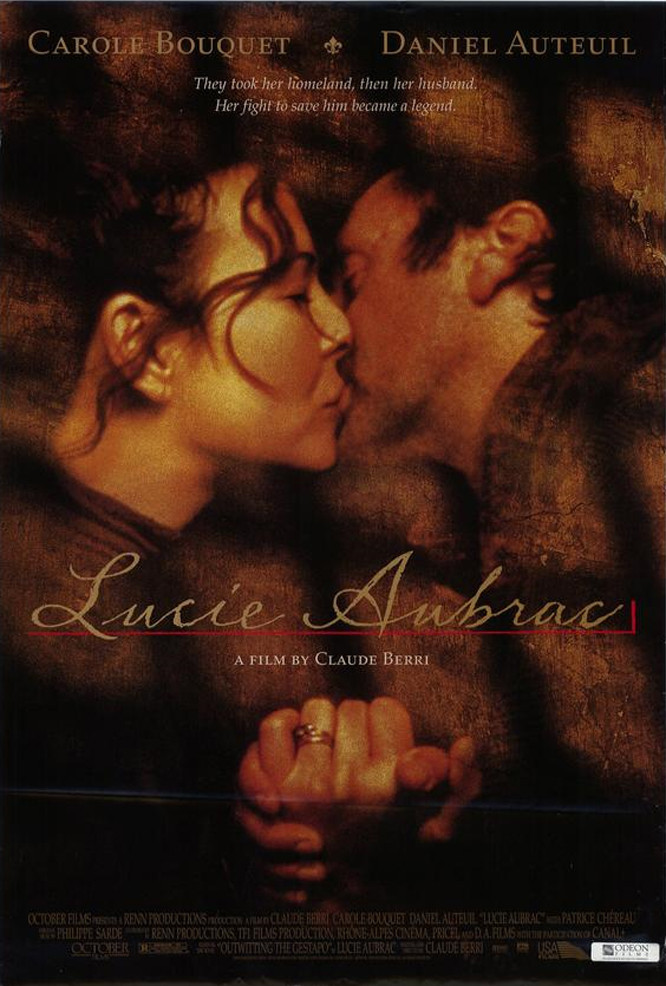

I must say, not enough. There are some moments of true tension, as when Lucie (Carole Bouquet) confronts local Nazi officials and claims that she is pregnant by the man they are holding prisoner, and wants to be married so her child can have a name. And there’s further tension when she is permitted to meet with her husband in front of the Nazis. He has claimed to be somebody else, has denied he knows her and now must somehow intuit that the time is right to admit his real identity–since her plan involves hijacking the truck that would carry him from prison to their wedding ceremony.

Those scenes work. Other scenes, including the planning and execution of the snatch, would not be remarkable if we saw them in a fiction film. They take on a certain interest because they are based on fact, yes, but the bones of the action are not very meaty. A map is drawn, showing an intersection of two streets. A plan is devised: Partisans will drive their cars in front of the truck, blocking it. Others will shoot the driver and guards. Raymond Aubrac and his fellow prisoners will escape. This is not the stuff of a caper movie.

Raymond is played by Daniel Auteuil, who has the best nose among French actors, ahead even of Gerard Depardieu (whose nose has been broken more often than Auteuil’s but with less dramatic effect). He is a wonderful actor (“Un Coeur en Hiver,” “My Favorite Season,” “Les Voleurs”). Here he seems constrained by the tradition of brave understatement which inflicts so many movie Resistance heroes. He is tender in quiet private moments with his wife, but otherwise is essentially a pawn in her scheme.

Bouquet is an enigma. A beautiful woman, she somehow lacks juice in this role. She is too perfectly coifed, dressed, made up; there should be more smudges on a girl who has been seduced and abandoned. Opportunities are lost in her meetings with Nazi officials, including one beefy general who in civilian life could have been typecast as a real butcher, in Lyon or anywhere. The confrontations are too dry, too restrained by unexpressed hostility. The movie has too much docudrama and not enough soul.

As a heroine, Lucie Aubrac has much to recommend her. After the screening, I informed my wife that in the event of my being taken prisoner by villains, I would expect her, like Lucie, to lead a raid to free me. She agreed. I hope she springs me before I crack under torture.