Here is a French movie about a family that is unhappy in so manydifferent ways that death is not a defeat but an escape. It is about theway a hurt in childhood can bend and shape an adult life years later,and about the way guilt may make us regret being selfish, but isunlikely to make us generous. It is a sad film, but not a depressingone; to some degree it is a comedy.

Andre Techine’s “My Favorite Season” is one of those intriguing films that functions without a plot, and uses instead an intensecuriosity about its characters. As it opens, an old woman (MartheVillalonga) has reached the point where she should no longer live alone.

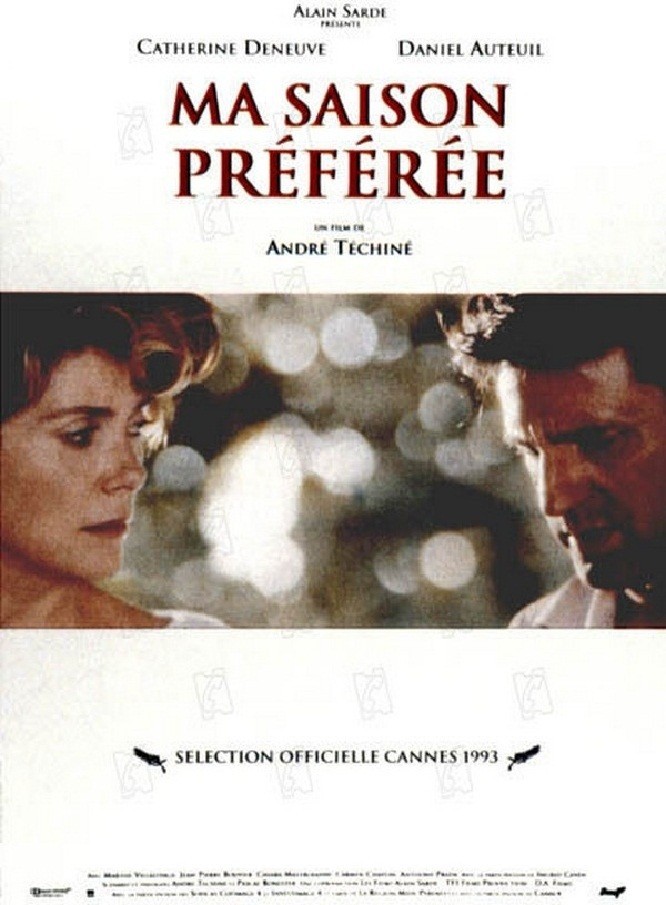

Her daughter (Catherine Deneuve) brings her home to live with herfamily, which includes a daughter (Chiara Mastroianni), an adopted son(Anthony Prada) and the son’s uninhibited Moroccan girlfriend (CarmenChaplin). There is also a husband (Jean-Pierre Bouvier), who is remotefrom the others.

The mother is not happy in the family’s bourgeois home inToulouse. She sits by the swimming pool in the middle of the night,talking fretfully under her breath (“Sometimes I talk to myself–it’sless exhausting than talking to someone else”). Deneuve goes to pay avisit on her unmarried younger brother (Daniel Auteuil), whom she hasnot seen for three years, since they quarreled at their father’sfuneral. He is invited to a Christmas dinner for the entire family. Soonwe will find that Christmas is probably not anyone’s favoriteseason.

Techine, the former critic who directed this film from ascreenplay by Claudine Taulere, doesn’t set up the story in terms ofgoals and setbacks. He is content to sit on the sidelines and watch,bemused. For a time we watch the behavior of the children. Auteuil walksin on Prada and Chaplin as they are making love, and later Prada andMastroianni repair to his bedroom with Chaplin and convince her to do astriptease. She is in the middle of it when their father walks in,distractedly, and leaves again. This family has so much on its mind thatstrange adolescent sexual behavior hardly registers.

There is, we gather, a lot of bad blood in the past. The husbandis not pleased to see his brother-in-law. The brother-in-law lockshimself in the toilet and makes resolutions (“Be nice, express aninterest, don’t get carried away”). The evening ends in a fistfight,and blood is shed–not much, but enough to convince the old mother thatshe should return to her home and no longer test her daughter’shospitality.

Now what about Deneuve and Auteuil? What happened in theirchildhood that has made them so skittish today? It becomes clear thatAuteuil passionately loves Deneuve, probably not in an incestuous way,but more in a possessive way. She was like a mother and a heroine tohim, and when she got married and left home, a wound opened up in hissoul that has never healed. He prays for an end to Deneuve’s marriage,and he nurses hopes that perhaps they can set up a household together.

The fate of the mother seems forgotten at times.

We watch this movie with interest because it watches itscharacters with interest. They behave with the unpredictability of realpeople. At one point, angry and disturbed, Deneuve deliberately slidesan expensive china clock off a mantel, allowing it to crash into pieces.

Why? Because it’s what she felt like doing. The movie feels no need toexplain every action.

There are perfect little moments in the film. A woman in a cafe,singing, “One day, he will die.” Deneuve’s memory of how her mothercould find mushrooms in the woods “like an animal.” Auteuil droppingfrom the balcony of his room deliberately to break his leg (we are leftto decide if he is acting out of self-loathing, or from a desire toinspire his sister’s pity). You leave this movie in the same way youleave family gatherings, aware that years of old aches, torments andresentments are simmering under the surface, and that it is probablywise to leave them there.