A truism when it comes to dining out? If you eat at a restaurant whose main selling point is that its towering height or location near a natural wonder affords a feast for the eyes, chances are the food there will fall into the category of a disappointing afterthought.

That can also be the case when it comes to films whose primary attraction is their visual pizzazz. Too often there is a lack of there actually there beyond the wow factor. Consider the gorgeous backdrops of the 1998 Robin Williams-starring afterlife fantasy “What Dreams May Come“: Looks, 10; story, ugh. “Avatar” might be the ultimate example of this syndrome as its eye-popping 3-D effects only underlined its barely multi-dimensional sci-fi screenplay.

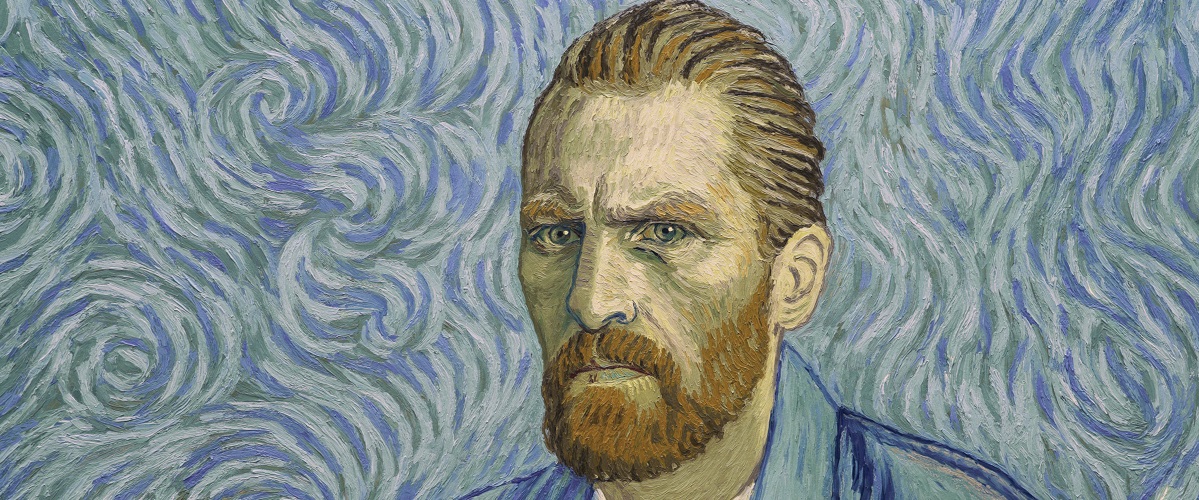

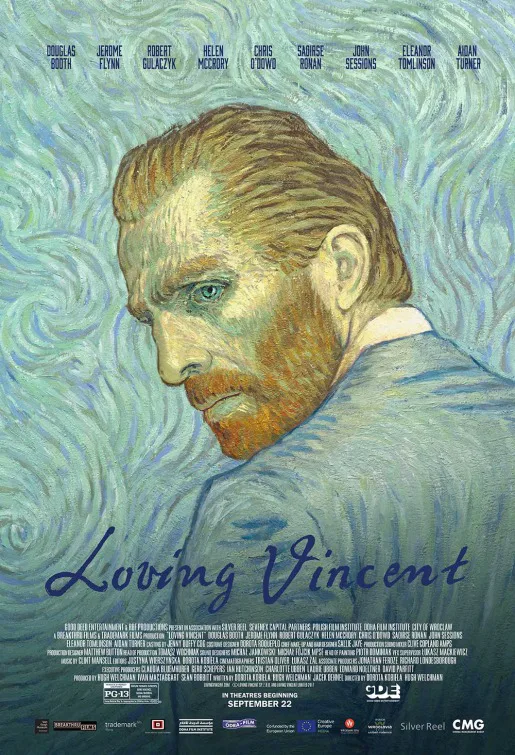

Faring slightly better script-wise is the ambitious animated biopic “Loving Vincent.” That would be Vincent as in Van Gogh, the tormented 19th-century Dutch painter, who absorbed the essence of then-popular Impressionism and re-imagined it with his trademark brawny brushstrokes. That technique lent a unique vibrancy to his vividly hued renderings of the French countryside and portraits of acquaintances that are highlighted in the film. As a result, his output seems to be uniquely suited for what is being sold as the first-ever fully painted feature film. This rather melancholy if stiff account of the artist’s final weeks before he died in 1890 from what he claimed was a self-inflicted gunshot is neither consistently riveting nor all that original. But the movie at least benefits somewhat from focusing on this singular tragic soul—yes, Van Gogh is shown famously cutting off his left ear—whose work continues to fascinate us today.

What is faultless, however, is the dedication and ambition of Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, the movie-making team behind this Polish-U.K. collaboration. Consider that this production required the services of 125 painting animators to create 65,000 oil-painted frames that incorporated 120 of Van Gogh’s better-known works–a process that took ten years to complete. If you ever wanted a masterpiece hanging in a gallery to come to life, your wish has been fully granted many times over.

Their visual experiment is intensely mesmerizing to watch as Van Gogh’s familiar stars radiate in the nighttime skies, flickering halos hover around candles, a river pulses with shimmery waves, rain falls like strips of rectangular confetti in shades of black and gray and golden wheat waltzes in fields. Bursts of kinetic energy vibrate in nearly every scene as if the screen were radioactive. But this electric surge is more than just window dressing. It captures the very reason why Van Gogh, whose genius was mostly unsung during his brief life, is often considered the father of modern art. A social misfit prone to bouts of depression, Van Gogh would devote the last decade of his 37 years to answering his calling. The result was over 800 oil paintings that bared his emotions in a way that offered a portal into the next century and continues to speak to us today.

But movies can’t live by beautiful undulating images alone. “Loving Vincent” takes the form of a mirthless murder mystery that integrates Van Gogh’s portraits and landscapes with hand-painted live-action footage of actors. This derivative detective story probes whether Van Gogh committed suicide or was shot by someone else. Assuming the role of investigator and narrator is Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), a bitter young man in a canary-yellow jacket who has a weakness for alcohol and barroom brawls. A year after the artist’s death, he is reluctantly tasked by his postmaster father (Chris O’Dowd) to deliver Vincent’s final letter addressed to his beloved younger brother, Theo. Armand heads to Paris, where he learns from noted paint supplier Pere Tanguy (John Sessions) that Theo met his own demise months after his sibling died. The elder man also fills him in on the history of Vincent’s transformation from an unemployable failure to a prolific producer of fine art.

From this point on, “Loving Vincent” follows the well-worn path of many a TV and film sleuth. With newfound respect for and curiosity about Van Gogh, Armand takes off to picturesque Auvers-sur-Oise and begins to interrogate those who knew Vincent during his last six weeks. That includes an innkeeper’s spirited daughter, Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson), who has mostly kind things to say about Vincent’s time as a guest, and the less-generous Louise Chevalier (Helen McCrory), housekeeper to Dr. Gachet (Jerome Flynn), the physician who treated him. A religious woman, she demonizes Vincent, declaring, “He was evil.” Then there is Gachet’s daughter, Marguerite (Saoirse Ronan), who may or may not have been romantically connected to Van Gogh. Each witness offers widely divergent opinions of the artist before he died. Not helping matters is that the gun involved was never found. Ultimately, viewers are left to form their own conclusions about what happened.

Style definitely trumps substance here, as most of the actors are better defined through their vocal performances rather than their shape-shifting physical presences. Van Gogh himself shows up primarily in moody black-and-white photographic-like flashbacks told from his point of view as played by look-alike Polish theater actor Robert Gulaczyk. In fact, my favorite scene involves a smiling little girl at the inn running to Vincent and briefly sitting in his lap as he sketches a chicken with skinny legs—just like hers, he teases. In those few minutes, he is momentarily at peace and smiling for once. Helping to set the right melancholy mood is a superb score by Clint Mansell, propelled by strings and piano.

Only a fool would fail to use a version of Don McLean’s ode to the artist, “Starry Starry Night,” to conclude “Loving Vincent” and, in this case, Kobiela and Welchman do exactly that. If you are hungry for dazzling eye candy and don’t mind a less-than-meaty narrative, this might please your palate.