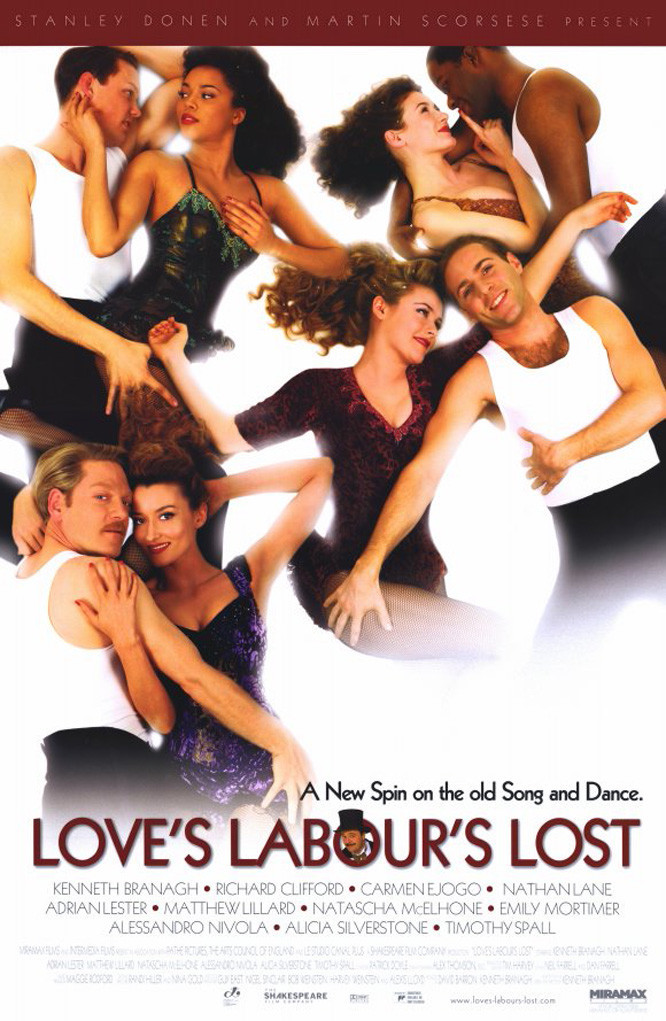

Shakespeare supplies not so much the source of Kenneth Branagh‘s “Love’s Labour’s Lost” as the clothesline. Using the flimsy support of one of the least of the master’s plots, Branagh strings together 10 song-and-dance numbers in a musical that’s more like a revue than an adaptation.

After daring to film his great version of “Hamlet” (1996) using the entire, uncut original play (the first time that had been done), Branagh here cuts and slashes through Shakespeare’s text with an editorial machete.

What is left is winsome, charming, sweet and slight. It’s so escapist it escapes even from itself. The story pairs off four sets of lovers, supplies them with delightful songs and settings, and calls it a day. The cast is not especially known for being able to sing and dance (only the British Adrian Lester and the Broadway veteran Nathan Lane are pros in those departments), but that’s part of the charm. Like Woody Allen’s “Everyone Says I Love You,” this is one of those movies where real people are so seized with the need to break into song that a lack of talent can’t stop them.

Not, in fact, that they are untalented. The songs here are well within the abilities of the cast to sing them, and indeed several of them were originally sung on the screen by Fred Astaire, whose vocal range was as modest as his footwork was unlimited. (Most of the songs have been recorded on albums by the British singer Peter Skellern, who can hit a note and the one below it and the one above it, and that’s about it–and he makes them entertaining, too.) The plot: The king of Navarre (Alesandro Nivola) has declared that he and three of his comrades (Kenneth Branagh, Adrian Lester, Matthew Lillard) will withdraw from the world for three years of thought and study.

During this time, they will reject all worldly pleasures, most particularly the company of women. No sooner do they make their vow and retire to their cloister than the princess of France (Alicia Silverstone) arrives for a visit, accompanied by three friends (Natascha McElhone, Carmen Ejogo, Emily Mortimer).

The men find it acutely poignant that they have sworn off the company of women (with a severe penalty for the first who succumbs). They search for loopholes. Perhaps if the ladies camp outside the palace walls, that won’t count as a visit. Perhaps if the visit is a state occasion, it is not a social one . . .

All of these rationalizations collapse before the beauty of the women, and the eight men and women pair off into four couples so quickly it’s like choosing sides for a softball game. Then we get the songs, some of them wonderfully well staged, as when “Cheek to Cheek” (with its line “Heaven . . . I’m in heaven . . . “) has them floating in air beneath the stars painted on the underside of the dome of the king’s library.

The eight starters are joined by low-comedy relief pitchers, in the tradition of all Shakespeare comedies. They include Timothy Spall as a Spaniard whose “I Get a Kick Out of You” is a charmer, and Nathan Lane (who does a nice slow-tempo “There’s No Business Like Show Business”). Alicia Silverstone is the lead among the women, who playfully do a synchro-swimming version of “Fancy Free,” and Branagh gives himself the best male role, although not tilting the scales to an unseemly degree.

All is light and winning, and yet somehow empty. It’s no excuse that the starting point was probably the weakest of Shakespeare’s plays. “Love’s Labour’s Lost” is hardly ever performed on the stage and has never been previous filmed, and there is a reason for that: It’s not about anything. In its original form, instead of the songs and dances we have dialogue that’s like an idle exercise in easy banter for Shakespeare.

It’s like a warm-up for the real thing. It makes not the slightest difference which boy gets which girl, or why, and by starting the action in 1939 and providing World War II as a backdrop, Branagh has not enriched either the play or the war, but fit them together with an awkward join.

There’s not a song I wouldn’t hear again with pleasure, or a clip that might not make me smile, but as a whole, it’s not much. Like cotton candy, it’s better as a concept than as an experience.