A creaky British writer, who has lived for decades in a cocoon of his books and his musings, locks himself out of the house one day in the rain. He takes refuge in a nearby movie theater, choosing a film based on a novel by Forster. After a time, he murmurs, “This isn’t E.M. Forster!” And he begins to collect his coat and hat so he can leave.

Indeed it is not Forster. The film is “Hotpants College II,” about the high jinks of a crowd of randy undergraduates. But as the writer, named Giles De’Ath, rises to his feet, he sees an image that causes him to pause. The camera slowly zooms in on his face, illuminated by the flickering light reflected from the screen, as he stands transfixed by the sight of a young actor named Ronnie Bostock.

It is this moment of rapture that gives “Love and Death on Long Island” its sly comic enchantment. Giles De’Ath, played by John Hurt as a man long settled in his dry and dusty ways, has fallen in love with a Hollywood teen idol, and his pursuit of this ideal leads him stumbling into the 20th century. He finds that films can be rented, and he goes to a video store to obtain two other Ronnie Bostock titles, “Tex Mex” and “Skidmarks.” Dressed like an actor playing T. S. Eliot, discussing the titles with the clerk as if he were speaking to a librarian in the British Museum, he rents the tapes and brings them home, only to find that he needs a VCR. He purchases the VCR and has it delivered to his book-lined study, where the delivery man gently explains why he also will require a television set.

At last, banishing his housekeeper from his study, Giles settles down into a long contemplation of the life and work of Ronnie Bostock. He even obtains teenage fan magazines (the cover of one calls Bostock “snoggable!”), and cuts out Ronnie’s photos to paste them in a scrap book, which in his elaborate cursive script he labels Bostockiana. He sneaks out to dispose of the magazines as if they were pornography and daydreams of a TV quiz show on which he would know all the answers to trivia questions about Ronnie (Favorite author: Stephen King. Favorite musician: Axl Rose).

These opening scenes of “Love and Death on Long Island” are funny and touching, and Hurt brings a dignity to Giles De’Ath that transcends any snickering amusement at his infatuation. It’s not even perfectly clear that Giles’ feelings are homosexual; he has been married, now lives as a widower, and there is no indication that he has (or for that matter had) any sex life at all. At lunch with his bewildered agent, he speaks of “the discovery of beauty where no one ever thought of looking for it.” And in a lecture on “The Death of the Future,” he spins off into rhapsodies about smiles (he is thinking only about Ronnie’s).

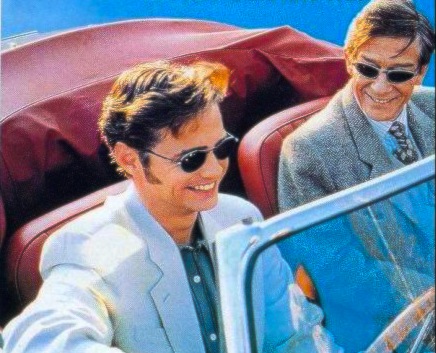

There is something here like the obsession of the little man in “Monsieur Hire,” who spies adoringly on the young woman whose window is opposite his own. No physical action is contemplated: Sexual energy is focused in the eyes and the imagination. The cinema of Ronnie Bostock, Giles believes, “has brought me into contact with all I never have been.” It is always a disappointment when fantasies become real; no mere person can equal our imaginings. Giles actually flies to Long Island, where he knows Bostock has a home, and sets out to find his idol. This journey into the new land is not without hazards for the reclusive London writer, who checks into a hot-sheets motel and soon finds himself hanging out at “Chez D’Irv,” a diner where the owner (Maury Chaykin) refers to almost everything as “very attractive.” But eventually Giles does find his quarry. First he meets Audrey (Fiona Loewi), Ronnie’s girlfriend, and then Ronnie himself, played by Jason Priestley with a sort of distant friendliness that melts a little when Giles starts comparing his films with Shakespeare’s bawdy passages. The film doesn’t commit the mistake of making Ronnie stupid and shallow, and Audrey is very smart; there’s a scene where she looks at Giles long and hard, as his cover story evaporates in her mind.

I almost wish Giles had never gotten to Long Island–had never met the object of his dreams. The film, directed by Richard Kwietniowski and based on a novel by the British film critic Gilbert Adair, steps carefully in the American scenes, and finds a way to end without cheap melodrama or easy emotion. But the heart of the film is in Giles’ fascination, his reveries about Ronnie’s perfection.

There is a scene in “Hotpants College II” in which Ronnie reclines on the counter of a hamburger joint, and his pose immediately reminds Giles of Henry Wallis’ famous painting “The Death of Chatterton,” in which the young poet is found dead on his bed in a garret. Thomas Chatterton was to the 18th century as Bostock is to ours, I suppose: sex symbol, star, popular entertainer, golden youth. It’s all in how you look at it.