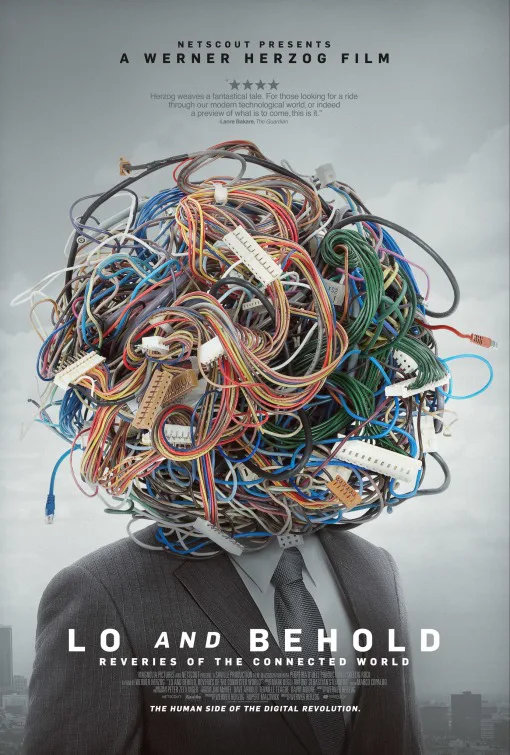

Werner Herzog contemplates the Internet. What more do you need to know about “Lo and Behold: Reveries of the Connected World”? The promises and pitfalls of the digital age is the perfect subject for Herzog, a rare filmmaker who’s a bigger personality than most of the people he makes films about—and considering the sorts of eccentrics, dreamers and madmen Herzog makes films about, that’s saying a lot. If your work entails programming or anything related to the nuts and bolts of digital technology, you’re unlikely to encounter anything in this brisk feature that you haven’t contemplated at length; but if you spend a good portion of your waking life online, as increasing numbers of viewers do, but take it for granted, you may appreciate the way Herzog comes into the the subject: from a borderline-layman’s perspective, wry and curious. He’s equally interested in the subjects being discussed and the personalities of the experts laying it all out.

The film is broken into ten chapters, each annotated like sections of a book, each bearing the sort of quasi-mystical or vaguely ominous title that you’d expect Herzog to affix: “The Glory of the Internet,”“The Dark Side” and so on. It is essentially a promotional film, financed mainly by the cybersecurity firm NetScout, but for all its insistence on the glory of interconnectedness and the transformations it has inspired, Herzog pays nearly equal attention to the downsides, particularly government and corporate surveillance and faceless cruelty. Like a lot of stories of human-created intelligence, in its heart this one is “Frankenstein.” A scientist who is inspired or mad, depending on your point of view, creates a child of sorts, and as the child grows into adolescence and adulthood, it starts to take on a life of its own, unsettling and threatening its creator to the point where it eventually seems to be telling the “parent” what to do, and even how to evolve.

The movie begins with a scientific “birth,” with shots of students walking in slow motion across the University of Southern California Los Angeles. The music is the opening of Wagner’s Ring, the Prelude to Das Rheingold; it was memorably used in Terrence Malick’s “The New World,’ but it is also associated, like all Wagner’s work, with Hitler, who adored Wagner and derived the philosophical underpinnings of Nazism from Wagner’s political writing. Many of Herzog’s filmmaking choices have that kind of double-edged appropriateness. As Herzog muses on the depressing ugliness of institutional hallways in an academic building on campus, we see a trim older gentleman, computer science professor Leonard Kleinrock, leading the camera through a doorway that leads to the room where the Internet was born in 1969. As Kleinrock shows us the first node in the Internet and talks about ARPANET, a government-supported data network that would use the technology later known as “packet switching,” Herzog doesn’t interrupt his lively, polished monologue. He seems delighted by Kleinrock’s brilliance, enthusiasm and showmanship. The viewer might expect the rest of the film to unfold in this mode, with the director interviewing various scientific founders and technology boosters, creating a gallery of inspirational character sketches along the way.

But two segments later, the film takes a sharp turn into despair and disgust as Herzog visits the parents and siblings of Nikki Catsouras, who was crushed and nearly decapitated in a car wreck in 2006. A highway patrolman at the scene took a photo of her corpse, as regulations required, but then forwarded it to colleagues, and somehow it slipped free and circulated everywhere, and the trolls got hold of it and immediately began tormenting her family by emailing them the photo with snide or vile captions like “Woo hoo, daddy! I’m still alive!” The family was so horrified that they withdrew from online life and homeschooled their youngest daughter. Catsouras’ mother flat-out tells us that she thinks the devil lives in the Internet and is slowly but surely making all of us more like him.

Herzog lets this incident stand in for the troll culture of anonymous harassment and emotional abuse, one of many downsides of the technology that at first was characterized as a gateway to greater understanding. As “Lo and Behold” unfolds, he alternates hopeful and grim stories with others in a minor key that could be taken both ways at once.

The section on driverless cars, for instance, optimistically sketches a future where a ride to work is stress free and traffic moves with hive-mind efficiency, then raises the chilling prospect of onboard computers having to make split-second, utilitarian life-and-death decisions, such as whether to crash into pedestrians or property to keep a car’s driver safe. An expert insists that the computer strives to do neither because it’s been programmed to adhere to Isaac Asimov’s first law of robotics—machines should never harm people or knowingly allow them to be harmed—but like every other choice in life, this one is not entirely in the decision maker’s control. Like other segments, this one evokes Clarence Darrow’s line from “Inherit the Wind”: “Mister, you may conquer the air, but the clouds will stink of gasoline and the birds will lose their wonder.”

Herzog makes a relaxed but alert guide throughout, using narration sparsely but memorably and letting us hear his offscreen voice asking questions, some of which seem merely prankish until you hear the answers. (When talking to a scientist who helped devise small, self-driving robot drones that can play football in teams, he asks if the most accomplished group of drones can out-think Brazil’s team. The answer: no, not at the moment, but don’t bet against them in 2050.)

The mosaic arrangement of material ensures that no one subject can be covered in detail—the sum total sometimes plays like a very good themed edition of “CBS News Sunday Morning” but with a wickedly funny narrator—and a couple of segments, notably one about a rehab clinic for gaming addicts, feel intellectually undercooked. The film is saved from mere competence by that Herzogian feeling, at once grandiose and self-deprecating. Herzog embodies the cliche about the performer who’s so charismatic that he could read aloud from the phone book and still be mesmerizing. An early segment informs us that during the early days of online activity, there was a printed directory containing the names and contact numbers of every person using the Internet. This document, we are told, is basically a phone book. It’s a good thing Herzog didn’t pause the film to read aloud from it. If he had, the Internet would have exploded.