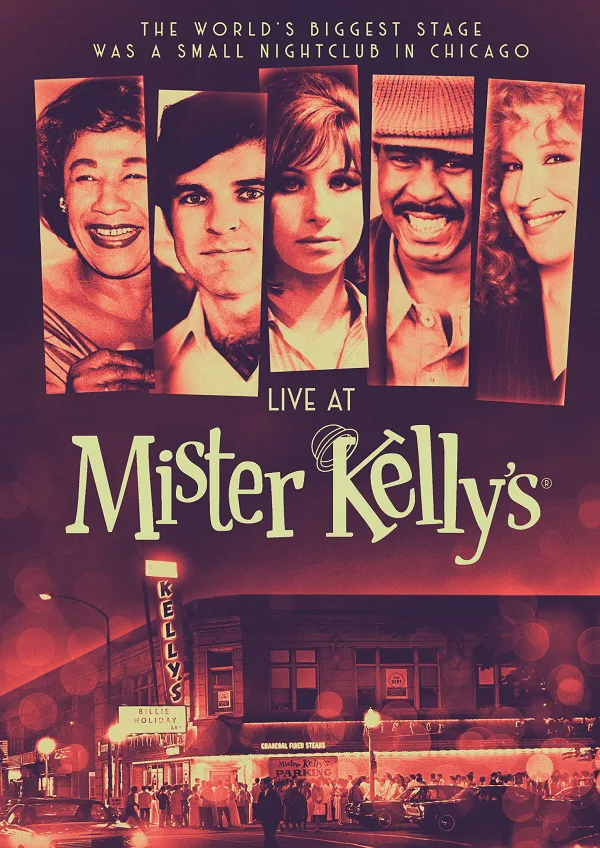

I never got to go to the celebrated Chicago nightclub Mister Kelly’s—it closed in 1975 on my fourth birthday—but as an avid student of the histories of both the city and of show business in general, I knew it was more than just your average run-of-the-mill hot spot. However, I’m not sure I ever quite grasped just how special or significant of a venue it really was until I watched “Live at Mister Kelly’s,” a fascinating new documentary from Theodore Bogosian now hitting video on demand. The documentary is about how Mister Kelly’s not only transformed from a nightclub into a institution, but helped to make the corner of Rush and Bellevue into arguably the epicenter of American popular culture during its heyday. That is, until vast changes in the entertainment industry as a whole made the existence of such a place economically unfeasible.

Narrated by Bill Kurtis, the film recounts the history of the club and its founders, George and Oscar Marienthal, two brothers and entrepreneurs who first found success in 1946 when they opened London House, a upscale supper club on Michigan and Wacker that regularly began booking jazz performers like Oscar Peterson and Ramsey Lewis. Buoyed by the success of that venture, they decided to expand and in 1953, they opened Mister Kelly’s a few blocks north of their original place. After a fire burned the original Mister Kelly’s down in 1955, it was rebuilt with a new sound system and over the next couple of years, it had already booked such talents as Sarah Vaughn, Ella Fitzgerald, and Della Reese. In 1959, the club introduced a new booking policy that would combine a musical act with a comedian, covering both established talents and up-and-comers who were on the verge of breaking through to the big time. Notably, the club had a racially inclusive booking policy that made it a rarity at a time when Black entertainers were still often kept from playing the best venues.

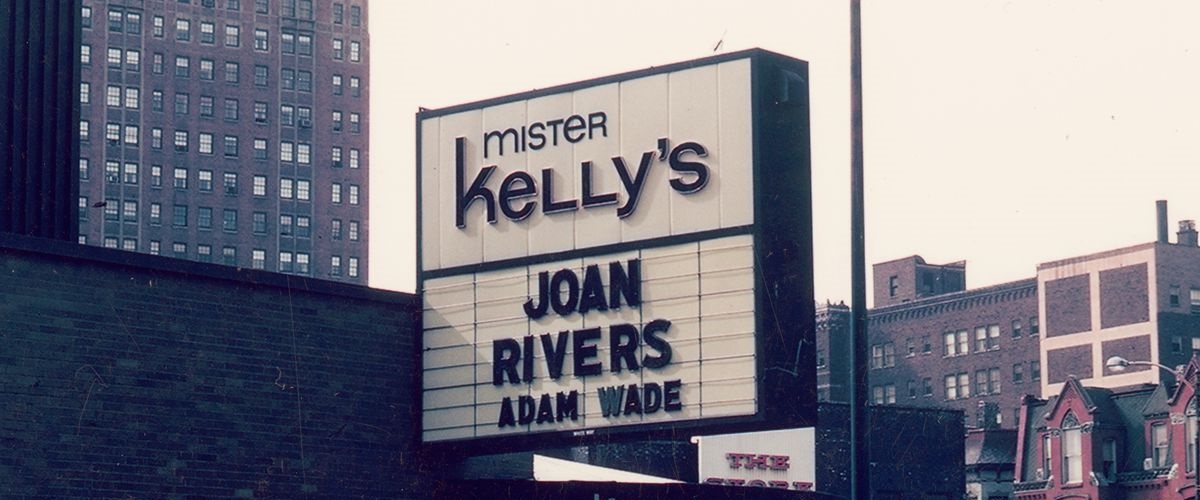

Over the next 16 years, the club would play host to a truly astonishing array of talents, catching many of them when they were still on the rise. A partial list of those who appeared on that stage during that time includes such luminaries as Billie Holiday, Lenny Bruce, Dionne Warwick, Julie London, Richard Pryor, Woody Allen, Mort Sahl (whose 1971 appearance was chronicled in an article by Roger Ebert), Bill Cosby, Carly Simon, Lainie Kazan (who was booked to play the night the place caught on fire for the second time in 1966 and who was the headliner when it reopened a year later), Joan Rivers, George Carlin, Aretha Franklin. Curtis Mayfield, Lily Tomlin, Dick Gregory, Nina Simone, Bette Midler and Steve Martin. A number of these artists recorded albums of their performances—the late Freddie Prinze did his only album there—and while it wasn’t technically a booking, even Warren Beatty appeared on its stage when he played a comedian on the run from the mob in Arthur Penn’s 1965 cult favorite “Mickey One.”

One of the club’s most famous bookings occurred when Oscar Marienthal visited a New York club early in 1963 and was so impressed with the 20-year-old singer performing there that he booked her for an appearance—that’s how Barbra Streisand came to perform at the club that June and used a picture taken during a photo shoot during her stay as the cover for her People album. Streisand herself appears in the film to recount this story, one of a number of people who played there back in the day and who still hold the experience in high esteem. Unfortunately, precious little film survives today of the performances that occurred there (we do get a short clip of Bette Midler at work and—Spoiler Alert!—she is a bit bawdy) but their accounts and memories are so filled with a genuine affection for the place that you almost feel as if you’re there as they are telling their stories.

While unavoidable, the lack of performance footage does hurt “Live at Mister Kelly’s” a little, and I also wish that Bogosian had gone into a little more detail regarding the day-to-day realities of operating such a racially diverse nightclub in the middle of a city that did not always reflect those same attitudes in other aspects. And yet, even though the film is ultimately not much more than an exercise in nostalgia, that’s hardly a bad thing when you’re delving into a past as rich as the one on display here. More importantly, when the mere idea of going out currently has many people still on edge, the film serves as a canny elegy to a time when the idea of going out to an intimate club for an evening of entertainment was the norm instead of a potential nightmare.

Available on VOD today.