Mort Sahl died this week at the age of 91. Read our tribute here and Roger Ebert’s legendary interview with the comedian below.

I went back to Mister Kelly’s the other night to catch Mort Sahl again, and found myself sitting next to a friend who writes for another local newspaper. He was there to do a story on the girl singer – a very good girl singer – who is also there, and when she’d finished singing my friend got up to leave.

I asked him if he wasn’t going to stay and catch Sahl, and he said he wasn’t. I asked him if he’d ever seen Sahl work, and he said no, he hadn’t, and he didn’t want to because Sahl was…well, paranoid, you know, and hung up on that political thing, and my friend didn’t do that number.

Well, what can you say? My friend left with his story about the girl singer, and I stayed and watched the finest, quickest, most intelligent comic mind in America at work. Because that is how I feel about Mort Sahl, you see, and so I can’t be reasoned with either, I guess.

Sahl does do the political thing during his current stand at Mister Kelly’s, but it is part of a juggling act that includes every other subject in the contemporary zoo. Every time Sahl opens here, the columnists report that he covered everything under the sun, and then they list everything under the sun to prove it: Agnew, Ralph Nader, Vietnam, General Motors, Lockheed, etc., etc., etc. And you get the point.

But what you can’t understand, unless you watch him work, is the way he keeps seven or eight subjects in the air at once, and gets a lot of his laughs by transpositions and the intercutting on non sequiturs that, once you’ve thought about them, aren’t. Here is Sahl, beginning with an explanation of his back brace and then winging it:

I got it in a car accident…a car ran directly into me, after I accused the CIA of…well, never mind…but they caught the guy who ran his car into mine…he was a lone assassin, his mother never loved him, he had never been a member of any political group…a loner, in short…they were unable to establish any motive…the classic American assassin. Right here, for example, I have a list of the documents that the Warren Commission has never declassified, and they include Jack Ruby’s dental charts, because Ruby bit Oswald to death, see…and, no, really, I broke my back in Albuquerque, New Mexico, when I drove my car off the road, and there I was down in this canyon, and a state trooper drives up in his Dodge Polara – not necessarily the lowest bidder – and orders me out of my car. I explain that I can’t stand up because I’ve broken my back, and, besides, I’m experiencing a heady intoxication from being alive in the Nixon-Agnew era…and he sees from my license plates that I’m from California, so he measures the flare of my pants, confiscates a bottle of Vitamin C and busts me…which is the second time I’ve been led astray by Linus Pauling.

The fundamental difference in style between Sahl and other comedians is that he doesn’t do a monologue, he does a tapestry. Almost all comedians do linear routines. The old-fashioned comics string together jokes – that most linear of all literary forms – and the newer comics impose some kind of an outside structure like autobiography, in order to give their essentially unrelated material the appearance of hanging together.

Sahl works in the opposite way, seeming to glory in the fact that his material seems incredibly diverse and unorganized. He moves from Muskie to air in your hot dogs to Radical Chic parties to Lenny Bruce to Freud, and then reminds himself he was talking about Muskie, and doubles back, and free-associates off the track in a new direction, and doubles back again, and keeps all of these subjects going for ten minutes at a time and then snatches a line out of thin air that somehow, miraculously, gathers everything together into one penultimate vision of America.

This style cannot be imitated because it’s more of a personal revelation than it is a method. It is probably the most complex verbal style yet produced by an American humorist, and in the way it reflects the moment-to-moment functioning of a restless mind, it is the spoken equivalent of some of William Faulkner’s prose.

And yet my friend wouldn’t stay for Sahl because…well, because of the political thing. Mort Sahl, you see, still believes that the CIA assassinated John Kennedy, and that Clay Shaw was up to no good down there in New Orleans, and that the two Kennedy assassinations are linked, and that the FBI’s hands aren’t clean in the James Earl Ray case. You will have to listen to Sahl’s evidence on these matters (including some disturbingly frank testimony he reads from the Shaw trial transcript) and make up your own mind about it.

My admiration for Sahl is based less on the tenacity with which he has pursued the political mysteries of the 1960s than in his style of doing so. I think it’s possible to like comedians despite their material; if Mort Sahl is funny, cynical and adroit in what he has to say about the assassinations, it should be possible to appreciate his art entirely apart from his subject matter.

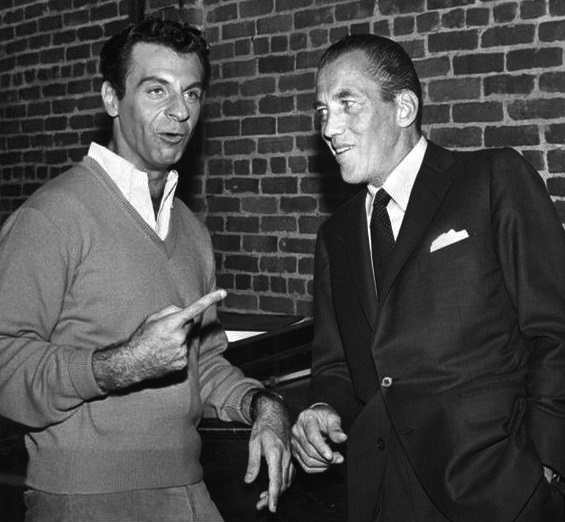

That was what Sahl was saying, in fact, about Marlon Brando, in a visit we had between shows. Sahl said he didn’t like Brando, but that he would stand in line to see him in a movie because he thinks Brando still has it, and will always have it. “You have to separate the man from the personal bias, and admire his art even if you can’t stand him,” he said. “There are a couple of musicians I also think about in that way.”

I had a list of questions I wanted to ask Sahl, about his career and his beliefs, but as it turned out we talked about movies for an hour. Sahl remembered a time when he was about 15, hitchhiking on Sunset Strip, and John Garfield picked him up.

“Do you young fellows know what this war’s about?” Garfield asked Sahl, “Do you know why we’re fighting in Germany?”

“Yes, sir,” Sahl said.

“Because if you don’t,” Garfield said, “there’s no use in going…”

Sahl let that thought hang in the air for a moment, and then we went on to other topics: Frank Capra, Sidney Poitier, the recent popularity of movies about losers, Nixon (“I’ve been doing stuff on him since 1953, and my lips are getting tired of forming the syllables”).

And then we got onto the Pentagon Papers. Sahl had claimed during his act that The New York Times hadn’t reprinted the Pentagon Paper for October 2, 1963, in which, he said, President Kennedy ordered all American troops out of Viet Nam, an order later withdrawn.

“Well,” Sahl said, “it’s all seeping down now. You can’t keep people in the dark forever. And the strange thing, the tragic thing, is that all those lies were told in the name of holding it together, of maintaining credibility. The dividend is that, today, no branch of government can be believed. In the movie ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,’ you had to strain to believe that there could actually be one corrupt Senator. Today, how many young people believe there are any Senators who aren’t corrupt to one degree or another?”

There was a silence on that note, too, and then Sahl got up from the couch where he’d been resting his back, and his wife helped him on with his brace, and he pulled a sport shirt over it and got ready to do his second show.

If his back hurts him on stage, he doesn’t reveal it, and he’s doing long sets of an hour or more, working hard and at the top of his form. This is his 13th engagement at Mister Kelly’s since the middle 1950s, and he seems to be working harder this time than when I’ve seen him before, as if to outdo himself and convince the audience they got their money’s worth.

As I left, he was talking about paranoia. “I’m going to erase that word from the dictionary,” he was saying. “There is a closure going on right now in America, between my paranoia, and the facts.”