Based on the autobiographical novel by artist Amélie Nothomb, “Little Amélie or the Character of Rain” is a bite-sized bildungsroman of the titular tot, born in Japan to Belgian parents. Marked by threes, itself a holy number, Amelie is the third child, and the story takes us from her birth to age three. This is the age at which, in Japanese culture, a child descends from the realm of the gods into the world of the everyperson. The word for this infantile holiness is okosama, or “lord child,” and “Little Amélie or the Character of Rain,” directed by Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han, takes us through the spirit of this very earliest coming-of-age with whimsy, cross-cultural commentary, and sometimes immovable sentimentality.

Baby Amelie (Loïse Charpentier) is slow to develop: slow to walk, slow to talk. But once she does, prompted by a bite of Belgian white chocolate, she does so with an almost instant proficiency. The film takes the idea of early childhood awareness, the phenomenon that children are far more privy to the dynamics of reality than they are able to voice, and provides its lead with the vocabulary to match. She operates out of loving obligation, immeasurable curiosity, and even spite, refusing to speak her brother’s name due to the ever-so-typical brotherly hassling.

With three youngins bounding around the home, the parents need a hand, and their landlady, Kashima-san (Yumi Fujimori), employs them with the help of the homekeeper and by proxy nanny, Nishio-san (Victoria Grosbois). But Kashima-san, traumatized by the war, is more concerned with Nishio-san maintaining the upkeep of her property than she is permissive of any emotional ties that may bind. As Nishio-san and Amelie become deeply entwined, “Little Amelie or the Character of Rain” becomes a story of both the wonders and the generational complexities of cross-cultural relationships.

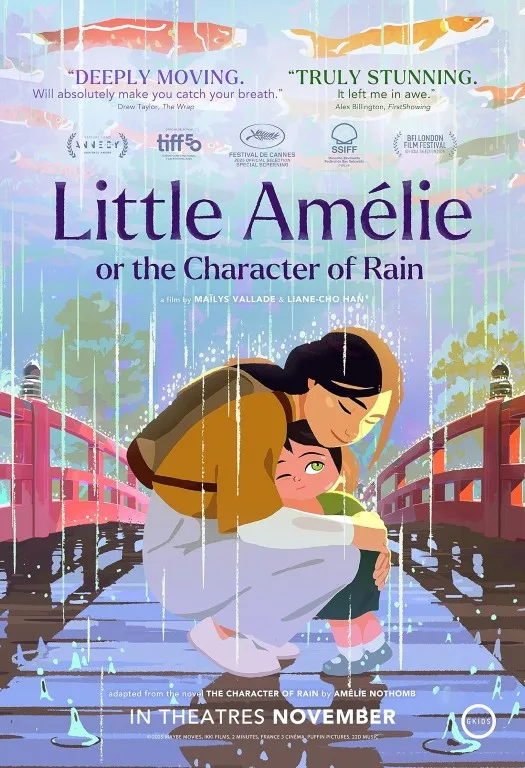

The film’s beautiful 2D animation crafts a generous, warm landscape that matches Amélie’s wide-eyed gaze, one that the film states is the defining quality of life. But the cornerstone of the film is wonder, and it accomplishes it beautifully. To Amélie, the vacuum cleaner is a magnificent beast; there’s whimsy in the quotidian, and when a tantrum arises, the magnitude is boundless. “Little Amélie or the Character of Rain” delivers charm excellently, mainly by highlighting how profoundly emotions and curiosity buoy the young (before the vehicles of logic and practicality begin to outline consciousness). The relationship between Amélie and Nishio-san is tender and sweet, prompting me to reminisce about moments with my nanny as a child and about how our own cross-cultural relationship has shaped me today.

But where the film falls short is in balancing tone. At times, its sentimentality tips into sappy, and when trying to be serious, it only half commits. Once, while cooking, Nishio-san flashes back to wartime, the pot boiling over as she discusses explosions, her hands mixing in the rice as she reminisces on digging through rubble. In form, it’s wonderful. In tone, it spawns sporadically, with emotional distance you wouldn’t anticipate from such memories. When it comes to Kashima-san, the film’s pawn of emotional diversity, she’s extremely underdeveloped. We know her stance but not her history, which makes it difficult to connect. The film posits her as crotchety and maybe bitter, leaving it up to the empathy of the audience to see her as traumatized and more complex than what she is afforded.

“Little Amélie and the Character of Rain” masters nostalgia, transforming Japan’s landscape into a playground of wonder and fantasy through the eyes of its lead child. While repetitive, the film’s romanticism is a reminder of the deified foundations of its story. It’s a love letter to the profundity of cross-cultural influences on upbringing, and gives nods to opportunities for understanding. A tender romp through time we’ve all seen long departed, and may only relive through children of our own, “Little Amélie and the Character of Rain” begs for the warmth of innocence, even when it pleads too hard.