“Don’t bring anything into the present that doesn’t have the past.” The great acting teacher Stella Adler told that to Marlon Brando once. He quotes it in “Listen to me Marlon,” a posthumous autobiography. It is made from clips of Brando’s screen performances, video of Brando being interviewed, and hundreds of hours’ worth of personal audio, including rambling messages that Brando would leave on friends and family’s answering machines, cassette tapes he recorded as experiments in self-hypnosis, and—well, who knows what some of this stuff is. A lot of it sounds like it could be outtakes from Brando’s performance as Kurtz in “Apocalypse Now,” muttering about errand boys and grocery clerks and gardenias and a snail crawling on the edge of a straight razor.

As written, directed and edited by Stevan Riley, the movie could have been called “Marlon Brando’s Tree of Life.” It slips back and forth between present and past throughout, sometimes in the middle of a sentence by Brando, connecting events from his often tragic old age, his prolific screen career, his tumultuous private life, and his childhood, which seems alternately lovely and hellish in Brando’s retelling. The actor’s ruminations are sometimes barely coherent but more often delightful: by turns bawdy, sentimental, self-pitying, self-lacerating, philosophical and bewildered. He seems to have been honest with himself, in these tapes anyway, about nearly everything, including his own dishonesty.

Born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska, Brando revolutionized screen acting by popularizing techniques he learned from Adler, which were themselves adaptions of ideas imported from Russian acting teacher Konstantin Stanislavsky. Adler was a big believer in sense memory, of tying present-tense decisions to emotional or biographical facts that had been established about the character, or to the actor’s own experiences. This process has as much to do with psychoanalysis as it does with art and craft, and that’s a big part of what made Brando, an uneducated but curious, brilliant and troubled man, the ideal ambassador for The Method. He took this new kind of acting from the stage to the screen, and make its processes comprehensible to laypeople simply by being Marlon Brando. “All of you are actors, and good actors, because you’re all liars,” Brando says at one point. “You lie for peace, you lie for tranquility, you lie for love.” Life is a performance, acting is a lie, therefore to be alive is to lie: that was the central idea of Brando’s life, uniting Brando the actor, the activist, the celebrity, the grotesque clown, the sex symbol, the old man and the boy.

No superlatives can do justice to Riley’s editing. His cutting confirms that the filmmaker hasn’t merely thought about what Brando’s life meant and what his work represented, but has taken the trouble to devise a visual scheme that mimics the way the waking mind jumps instantly between past and present, reality and imagination, within the course of a second or two, so that we really do feel as though we’re inside Brando’s mind. You could call the editing Godardian or Malickian (as in Terrence—the “Tree of Life” reference above was no joke) or you could simply say that this is a rare case where the style of a piece joins so tightly with the substance that distinguishing between the two becomes impossible.

There’s a lot of what you might call “biographer’s intuition” in the editing, as when the movie cuts from Brando talking about how his cold and volatile father used to beat him (“He used to slap me around, and for no good reason”) to a moment from the 1951 version of “A Streetcar Named Desire” where Brando’s Stanley Kowalski pounds a kitchen table and leans across it to intimidate Vivien Leigh’s Blanche DuBois.

There are plentiful re-creations of Brando’s childhood and his final days. But where a lot of documentary re-creations seem ethically suspect, even cheap, these are done with imagination and taste and a poetic sensibility. The camera prowls through Brando’s Beverly Hills home, revealing that his living room was as cluttered a place as his mind. It looks out on backyards through wind-blown curtains, and peers at the near-silhouette of a young woman at the other end of a Nebraska farm house: Brando’s mother, back-lit by sun streaming through a window.

Brando’s mother was mentally ill. His narration suggests that two of his 17 children, at the very least, seem to have suffered from some variant of it. Brando’s daughter Cheyenne committed suicide after many attempts, not long after her half-brother Christian, described by Brando as a troubled kid, killed her allegedly abusive boyfriend Dag Drollett and ended up on trial for murder. There are intimations that Brando himself was, if not officially mentally ill himself, then terrified of the possibility that he might be, and fascinated by the possibility that everyone, perhaps even medically “normal” people, feel and remember life in an ultimately non-rational, uncontrollable, impulsive and indescribable way—that maybe, to put it colloquially, we’re all crazy, and it’s all a matter of degrees, and normalcy is the illusion, the phantom we’re all chasing.

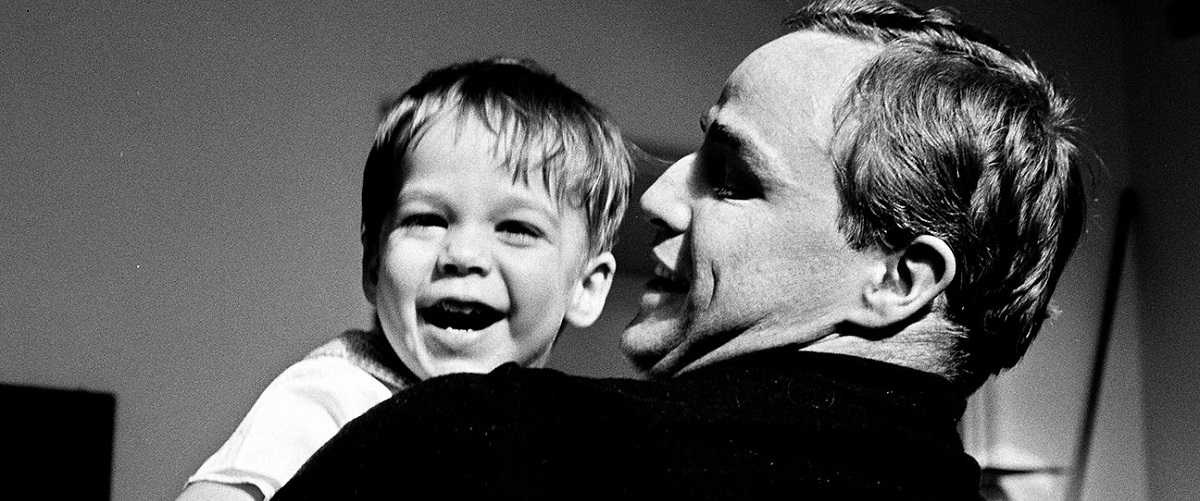

There is a constant, restless sense of exploration in every minute of this movie. Riley plays hunches, ties events to other events, decisions to other decisions, as a knowledgeable and imaginative biographer might. Some of the “childhood” images rhyme with home movie and video footage, taken by Brando himself, of the island in Tahiti that he eventually bought with the fortune he’d made by acting. Here, as throughout “Listen to me Marlon,” the movie guesses at how Brando’s childhood and young adulthood, fantasies and dreams, informed his choices, from what role to play and how to play it to what to do with the money he made by playing it.

Both the home movie footage of Tahiti and the first-person-seeming images from Brando’s childhood are deliberately evocative of “paradise” or “heaven,” but even as you’re aware that Brando is greatly oversimplifying the Tahiti and its people (“They do not know that you’re a movie star…they could not care less”) you’re also aware that there’s more going on here than an American buying a tiny South Pacific island. Issues are being worked through, just as they’re being worked through when Brando goes on TV in the 1960s and 1970s to champion African-American Civil Rights and Native American political struggles, describing them in terms of abused and abusers, underdogs versus bullies. Brando was criticized, even mocked, for going on national TV and proclaiming that white Americans were living on stolen land, and that the specters of slavery and the Native American genocide loomed over the nation’s self-image, but with each passing year his statements seem less provocative than undeniable and obvious; collectively we’re catching up to him. The shadow of Brando’s father hangs over his life as a political activist, as surely as his relationship to his mother and father inform his artistic explorations as an actor. The the juxtaposition of Brando’s life, work and words helps us see this.

The movie’s major, perhaps only, fault is that its brilliant construction denies it the storytelling clarity and basic insights that conventional nonfiction films provide. Although Riley moves through the actor’s life in a more or less linear way, we’re not always clear on the details of Cheyenne’s suicide and Christian’s act of violence, or the relationships between Brando and his various wives and girlfriends, or the sequence of events that connected one film to another, one cause to another, one scandal to another. But considering that the whole thing is a stream-of-consciousness exercise, rather like the ones that helped produce Brando’s searingly autobiographical performance in “Last Tango in Paris,” this was probably inevitable.

The movie is organized around images of Brando’s head, scanned some time before his death so that his performances could be re-created or perhaps mimicked once technology improved. These shots have the feel of a confession by the filmmaker: This is not Marlon Brando, it is an incredible simulation. Marlon Brando is dead, and I am bringing him back to life and putting words in his mouth. Would Brando approve? We’ll never know, but there’s a line near the end where he says that he wants to be buried with a microphone in his coffin so that once he’s dead he can begin narrating the experience. This film is as close as we’ll get to seeing his wish come true.