“Lipstick & Dynamite, Piss & Vinegar: The First Ladies of Wrestling” tells us just enough about the early days of professional women wrestlers to suggest there must be a great deal more to tell. The documentary visits elderly women who, then and now, can best be described as tough broads, and listens as they describe the early days of women’s wrestling. What they say is not as revealing as how they say it; as they talk we envision, not a colorful chapter in show-biz history, but a hard-scrabble world in which they were mistreated, swindled, lied to, injured, sometimes raped or beaten — and tried, it must be said, to give as good as they got.

The documentary, by Ruth Leitman, does an extraordinary job of assembling the survivors from the early days of a disreputable sport, beginning with Gladys “Killem” Gillem, whose sideshow act began as a change of pace from the strippers. Footage from the late 1930s and 1940s includes a sideshow barker describing the unimaginable erotic pleasures to be found inside the All-Girl Revue. I remember such sideshows at the Champaign County Fair, where you worked your way past the Octopus and the Tilt-a-Whirl to the girlie tent, always at the bottom of the midway, where dancers in ratty spangled gowns paraded before we horny teenagers and then the barker said, “All right, girls, back inside the tent!” We followed them in, slamming down the exact change; if a murder had taken place during the show, there would have been no witnesses, because there was absolutely no eye contact between the sinners.

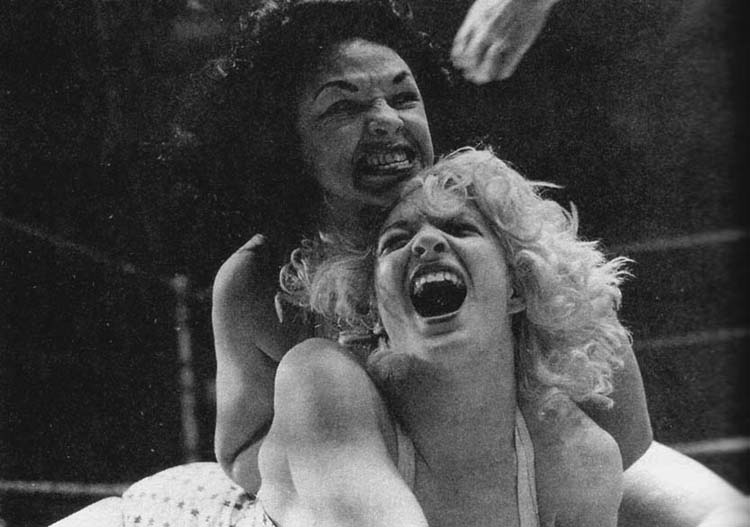

But I digress. The appeal of women’s wrestling, then and, I suspect, even now, had a lot to do with the possibility of a Janet Jackson moment. But the sideshow wrestlers gave way to a sport that toured the same venues as men’s professional wrestling; sometimes the women were the curtain-raisers, although, as they tell it, the men were terrified that women would become a bigger draw. We meet such legends of the sport as The Fabulous Moolah (Lillian Ellison), who was the biggest star of the sport and had the most longevity, surviving even into the heyday of the WWF and finding a new generation of fans.

Moolah, now in her 80s, still works as a wrestling promoter. We get a glimpse of her home life; she lives with the Great Mae Young and Diamond Lil, a dwarf wrestler, in a household that would give pause to John Waters. Although Moolah and Young are apparently a couple, the role of Diamond Lil becomes harder to define the more Moolah praises her skills as an invaluable maid of all work. Among the film’s other unforgettable characters are Penny Banner, “The Blond Bombshell,” and Ella Waldek, who sounds as if she has chain-smoked Camels from birth, and later went into the detective business.

Men seem to have come into the lives of these women primarily as exploiters, rapists and occasional transient husbands. The promoter Billy Wolfe, a key figure in the early days, is remembered without affection for taking half of what he said were their earnings, and sleeping with as many of them as he could. When the women describe their sexual experiences, their voices reflect more hardened realism than indignation. They were often abandoned when young, made their way on their own, paid their dues.

Magicians have a credo: “The trick is told when the trick is sold.” They don’t give away their secrets for free. Neither, I suspect, do women wrestlers. Glimpsed on every face in this movie, echoing in every voice, are hints of the things they’ve seen and the stories they could tell if they didn’t have a lifelong aversion to leveling with the rubes. What we get is essentially the press-book version of their careers, which is harrowing enough; Ruth Leitman is said to be working on a fictional screenplay based on her material, and I have a suspicion it may be blood-curdling. At the end of the film, at the Gulf Coast Wrestlers’ Reunion, there is not a lot of sentiment, and no visible tears. One woman after another seems to have attended in order to say, “I’m still here,” as if being alive after what they’re been through is a form of defiance.