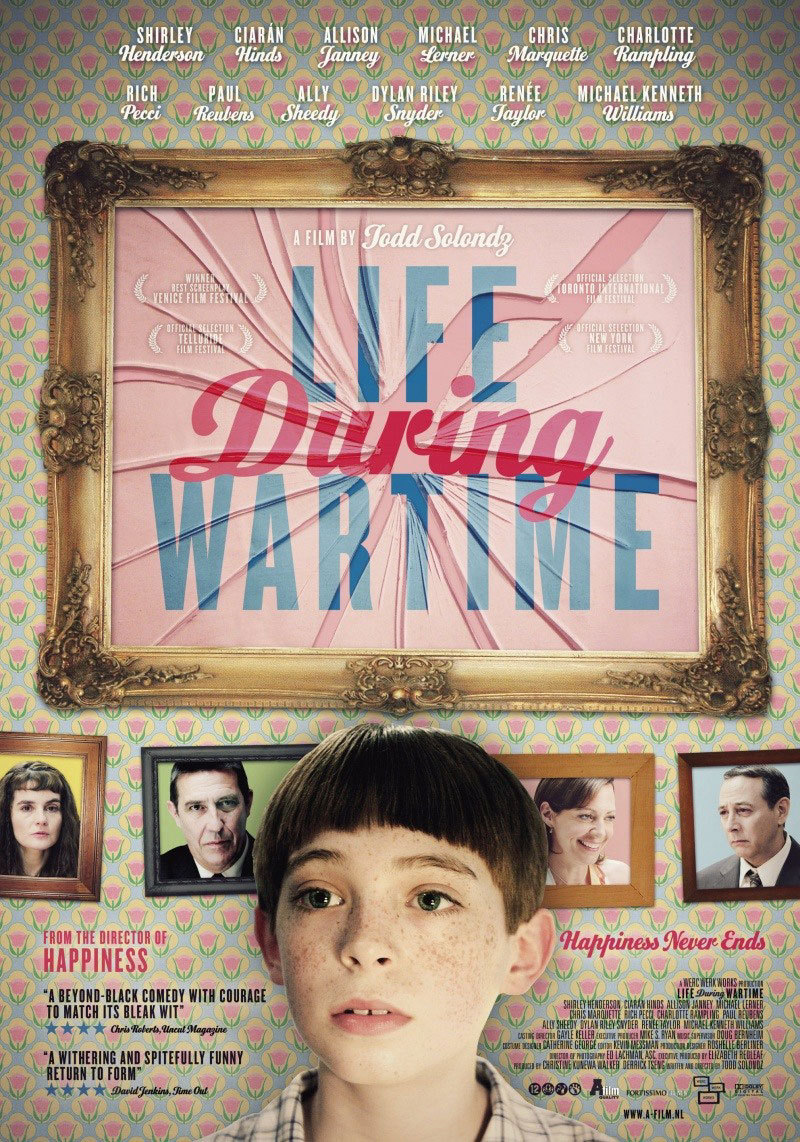

There’s always rationing in wartime. What’s rationed in Todd Solondz’s “Life During Wartime” are feelings of hope, kindness and optimism. His people are disturbed, pleading and often perverse, and indeed some of them are so badly off, they’re dead and must appear as ghosts to make their complaints. Always the kvetching, from beyond the grave yet.

Solondz describes the film as “a quasi-sequel” to his great “Happiness” (1998). If ever there was a film where the characters’ lives were over at the end, it’s that one. Solondz brought closure. Now 12 years later, wondering what happened to his people after that film ended, he approaches entropic collapse.

Well, they aged at different rates. They turned into different people, played by different actors, while keeping the same names. Allen, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in the first film, morphed into a black man (Michael Kenneth Williams), although Hoffman and Williams are still two of the only three actors in either film with three names. The genders of the various characters are the same, although the gender behavior is far from conventional. These people are stuck in their minds and can’t bring happiness to themselves or others. Only the children can be happy, and in the Solondz world, their innocence is a time bomb.

I could supply here a listing of the major characters in the 1998 film and the actors who played them. Can you remember the names of movie characters for 12 years? I can’t, not unless they’re named Marge Gunderson or Anton Chigurh. But in this film, Joy (Shirley Henderson) talks like a middle-age little girl, and once again finds herself stuck in restaurants in mutual misery with a man. This time it’s Allen (Williams), who has moved on from dirty phone calls and wankery to gang-banging and despair.

The man with whom Joy had her agonizing date in the first film now has become the dead Andy (Paul Reubens) whose ghost torments her (again in a restaurant booth) with piteous pleas. Later, Allen also appears to her as a ghost, urging her to kill herself. Her men have a way of not getting everything done in one lifetime.

Trish (Allison Janney) has moved to Florida to help her children escape the reputation of their pedophile father. They think he’s dead. But Bill (Ciaran Hinds) is on parole and unwisely wants to meet his older boy at college. Trish is dating Harvey (Michael Lerner), so devastated by a divorce he fears he’s forgotten how to perform sex. To the degree that he remembers, he’s sure that he can’t. Trish’s younger son, Timmy (Dylan Riley Snyder, in a performance that evokes great sympathy), is preparing for his bar mitzvah when he discovers his father was a pedophile — not good news on the day he is to become a man.

Trish has tried to break with her past and start anew in Florida. Helen (Ally Sheedy), her sister, is a thriving Hollywood screenwriter, driven and unfulfilled. Joy is the third sibling. For these three sisters, Chekhov would be the Marx Brothers. One of the best performances in the film is by Charlotte Rampling as the last woman in the world who Bill, the reforming pedophile, should choose as his partner in grown-up sex. These people live in interiors as barren as demonstration homes. They don’t have much stuff around. Ed Lachman, the cinematographer, almost sees them as on a stage set “suggesting” the rooms where they live.

This is the Solondz world. I think he’s a brilliant filmmaker. He evokes so effectively his own point of view, which is appalling and compulsive. You can imagine his screenplays being read aloud in his distinctive voice, which seems to embed in every word a querulous complaint against — well, everything. When he’s good (“Palindromes,” “Storytelling,” “Welcome To The Dollhouse“), few can touch him. Here he’s made a film that is sad without energy, dead without life. As a sequel to “Happiness,” it regards the same lives, then as tragedy, now as farce.