The late French filmmaker Chris Marker, who died in 2012 at the age of 91, was a pioneer of what some critics call the “essay film,” but he’s best known for his (perhaps) entirely fictional short, the seminal 1962 time-travel tale “La Jetée.” That less-than-a-half-hour movie is a massive influence on almost every sci-fi piece on time-travel since, not to mention a direct, credited inspiration for Terry Gilliam’s visionary feature “Twelve Monkeys.” He never made another film like it, at least directly like it. But every one of his nearly 60 other films are intimately tied to that masterpiece, because they are all about human perception and history and memory, and how they all warp our lives.

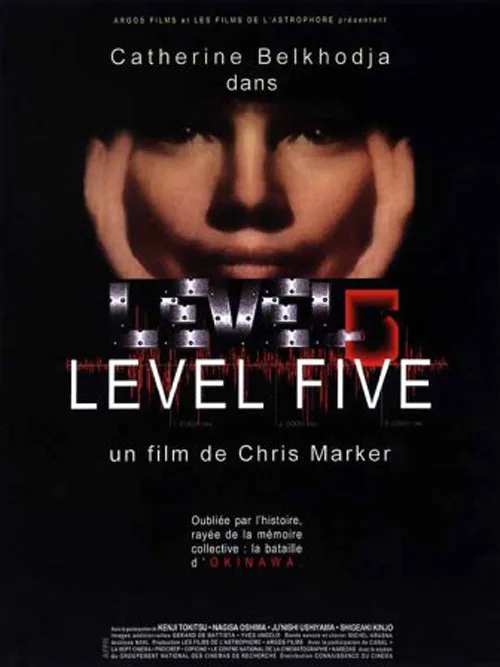

His 1997 movie “Level Five” is only now getting a release in the United States, and it’s a fascinating hybrid. Shot with low-budget equipment suited to a putatively rough-and-ready aesthetic, it’s a fictional documentary examining the battle of Okinawa in World War II, a conflict that, by Marker’s lights, helped usher in the terrifying atomic age in which we still live. Marker’s other works, remarkable movies such as “A Grin Without A Cat” and “Sans soleil,” bracing, personally inflected treatments of historical studies and anthropology, established the filmmaker as someone for whom the idea of “objective” history is thoroughly objectionable. So here he treats Okinawa through a fictionally contrived premise: the labors of Laura (Catherine Belkhodja) a computer enthusiast and video game developer, as she tries to develop a strategy game based on the battle—a cyber rewrite of history, in a sense. Marker’s narrator lightly interrogates Laura, who keeps a video diary of sorts, and teases the unseen filmmaker with personal reminiscences of their relationship, for instance, recollecting the first time they heard David Raksin’s musical theme to Otto Preminger’s film “Laura” together.

“What’s that got to do with Okinawa?” you may well ask now, and I’m not sure the movie will give you a satisfactory answer. All of Marker’s philosophical explorations are tinged, at the very least, by his own cinephilia (like many French filmmakers of his generation, he was active as a critic and in a sense remained so throughout his life), and for those who like their probings into historical trauma straight down the alley and digression-free, “Level Five” will be a very frustrating and arguably overly French experience. I say “French” because the movie partakes in a kind of discourse that’s very much in a French intellectual tradition, the discursive semiotic inquiry in which one’s own cast of mind is necessarily grist for the cerebral mill. In other words, it’s Marker’s position that he cannot make a film “about” Okinawa even if he and his cinematographer travel and shoot there (which they did); he can only make a film about thinking about Okinawa. That being what this is, if you can hook into it, “Level Five” is not just witty, insinuating, and penetrating; it’s also unexpectedly moving and, as deliberately threadbare as it often looks, cinematically rich. Its imagery derives directly from a time when computer graphics were so much cruder than they’ve become that it’s almost difficult to believe. Laura’s interaction with protocols, mysterious individuals in user groups and chat rooms of the late ‘90s, underscores the way technology is constantly seeming to redefine epistemology; this makes “Level Five” a kind of prophetic text in a way perhaps Marker himself didn’t even anticipate. Is it a “masterpiece?” Who’s to say; but like every other film Marker made, it’s an exemplary and resonant address on the life of the mind and the life outside of that one.