Teresa works as a frozen-chicken packer, wrapping the giblets in plastic and shoving them back where they came from. Elaine is out of work. They hang out together in the working-class pubs down by the docks of Liverpool, and although they are not exactly criminals, they aren’t above sweet-talking a drunken businessman until they can finger his wallet. On weekends, they look for a break in the monotony. And one night, while drinking up Teresa’s earnings from the chicken factory, they pick up a couple of Russian sailors.

One of them, Sergei, is interested in one thing only – sex – and that’s what Teresa’s looking for, too. Teresa is a faded blond with a big personality and a certain desperation. The other sailor, Peter, seems different: quieter, somehow, and more sincere. That appeals to Elaine. After a night of pub-crawling, Teresa pays for rooms in a waterfront hotel, and while she and Sergei party in their room, Elaine and Peter talk all night long. Something unexpected has happened: They have fallen in love.

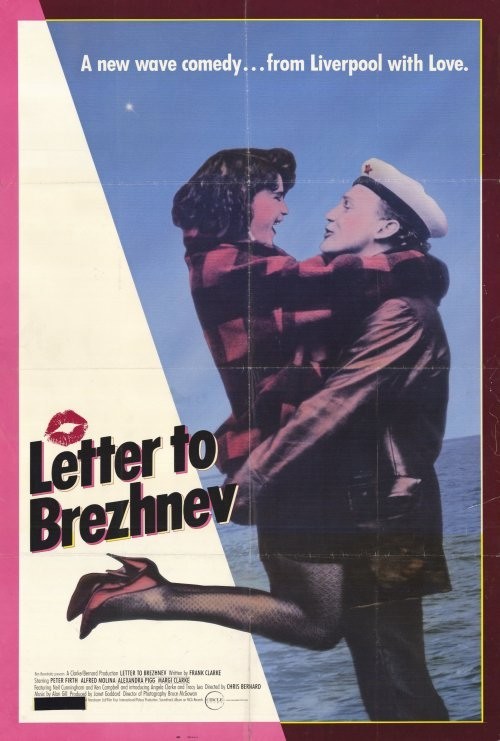

And that is the premise of “Letter to Brezhnev,” another one of those small-scale, intensely human movies that have come out of England in the last few years. Like “Mona Lisa,” it was financed by Channel 4, the British TV operation that is open to unusual projects such as this.

The movie doesn’t have big stars, it doesn’t have an earthshaking story to tell and it’s not ashamed of its Liverpool accents; in fact, it’s proud of them.

The relationship between Elaine and Peter is one of those all-night moments of truth that we all have, from time to time, when we are suddenly seized with the conviction that the person we have just met is the one person in all the world who can understand us the best.

Talk becomes more important than anything else; the most passionate hunger is not for sex but for understanding. Giant truths are exchanged about the stars, about time, about the nature of life. The two personalities line up side by side and face all of the rest of the world, united by truth.

Alas, few of these moments of instant communication last very long. It is always easier to agree about the nature of the galaxies than about everyday matters. But Elaine and Peter believe they will be different, and in the cold light of morning they pledge to love each other forever and, someday, to get married. Then Peter gets back on his ship and sails back to Russia and Elaine waits for word about their wedding plans.

If this were an ordinary story, that would be that. Peter would never be heard from again, Elaine’s memories would quietly fade and life would go on. But Elaine is more stubborn than that. Her life has been changed by the meeting with Peter, and she remains faithful to the spirit of that night. When no word comes, she takes matters into her own hands and writes a letter to Leonid Brezhnev, then the Soviet leader, asking to be reunited with the man she loves. The response (somewhat improbable, I agree) is a ticket to Moscow.

Should she go? Can she be happy in Russia where she will always be an outsider and where Peter’s work will keep him at sea for long periods of time? Does it matter if she will be happy? She has nothing now, she says, and if she does not take a chance, she will never have anything. This is as far as her thinking goes, but it is far enough.

“Letter to Brezhnev” is strong because it is simple. It is not really about romance at all. It is about how idealism can be a way of escaping from the rat race. It is about a young woman with the courage to try something dramatic to break out of the trap she’s in. It is also about a brave new tradition in British filmmaking, in which the heroes are ordinary people, seen with love.