Tanya’s fiance was going to meet them in England, but he is not at the airport, the rat. The Russian woman with the small boy and the uncertain English tries to deal with British immigration officials, who are not unkind but have seen this scenario countless times before. She talks about her fiance, she cites vague employment plans, and finally, in desperation, she requests political asylum.

Asylum is not really what she wants, but it’s what she gets: asylum inside the British bureaucracy, which ships Tanya (Dina Korzun) and her son Artiom (Artiom Strelnikov) to a bleak and crumbling seaside resort named Dreamland. There she’s given some food coupons and a barren apartment, and told the wait for a decision may take months, or years.

Tanya learns over the telephone that the fiance is never going to show. But in making the call she has also made a crucial connection; using an unfamiliar phone card at a run-down seaside arcade, she meets its owner, Alfie (Paddy Considine). He is an enigma, a seemingly nice man who perhaps has a subtle romantic agenda, or perhaps simply feels sorry for her and wants to help. Having been betrayed by her fiance, Tanya is not much interested in a new man. But Alfie doesn’t push it.

The movie was directed for the BBC films division by Pawel Pawlikowski, who has a background in documentaries and does a good job of sketching in everyday life in the area, where the cold concrete and joblessness of a housing project has bred a generation of young outlaws. It’s not clear whether the barbed wire is to keep people out, keep them in, or simply supply a concentration camp decor.

Young Artiom is an enterprising lad who makes friends with Alfie more quickly than his mother will, and is soon hanging out in the arcade, finding his niche in the Dreamland ecology. (“Mom, why can’t we stay here with him?”) His mother, desperately poor, fields a job offer from a pornographer named Les (Lindsay Honey) who wants to pay her to writhe on a bed for his Internet customers (he demonstrates with a teddy bear, in a scene balancing humor and the grotesque). Les is a sleazeball but a realist, the heir to generations of Cockney enterprisers. He points out that Tanya at least will not have to see, or be touched by, any of her “clients,” and that the money’s not bad. Such employment would be a change; in Russia, Tanya was an illustrator of children’s books.

It’s intriguing the way Pawlikowski keeps his hand hidden for most of the movie. We can’t guess where things are headed. The movie is not on a standard Hollywood romantic arc in which the happy ending would be Alfie and Tanya in each other’s arms. That’s only one of several possibilities, and economic factors affect everything. Dina Korzun’s performance holds our interest because she bases every scene on the fact that her character is a stranger in a strange land with no money and a son to protect. “Last Resort” avoids all temptations to reduce that to merely the setup for a romantic comedy; it’s the permanent condition of her life.

Some movies abandon their soul by solving everything with their endings. Life doesn’t have endings, only stages. To pretend a character’s problems can be solved is a cheat–in a realistic film, anyway (comedies, fantasies and formulas are another matter). I like the way “Last Resort” ends, how it concludes its emotional journey without pretending the underlying story is over. You walk out of the theater curiously touched.

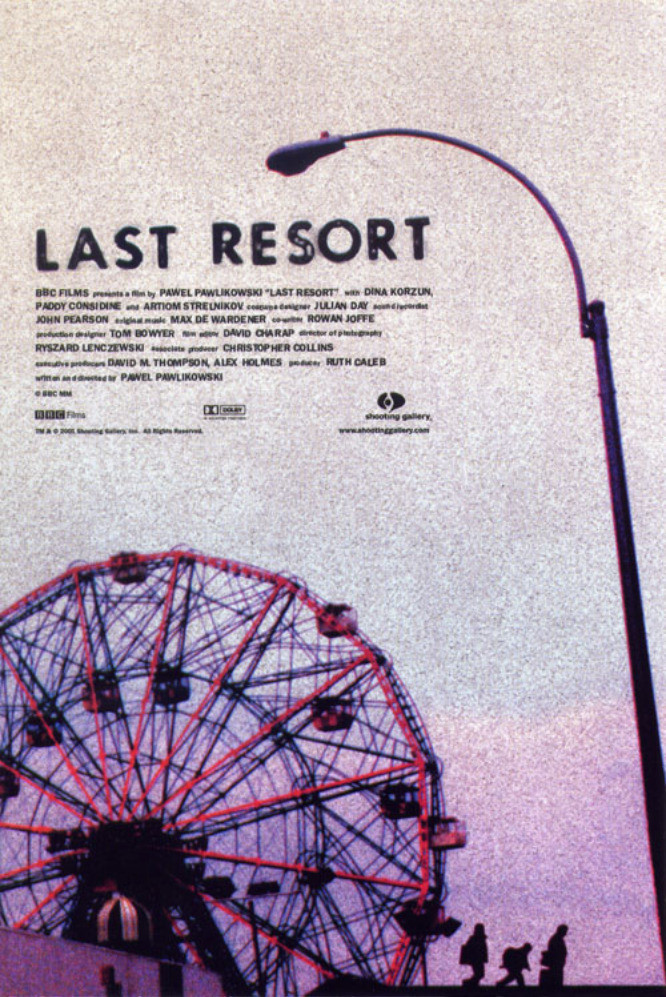

“Last Resort” opens the third season from the Shooting Gallery, which packages six independent films for two-week runs in Loews Cineplex theaters in 17 cities. Other titles in the spring series include the British “The Low Down,” the Cannes Critics Prize winner “Eureka” from Japan , the Iranian “The Day I Become a Woman,” the U.S. indie “Too Much Sleep ” and “When Brendan Met Trudy ” from Ireland.