On November 19, 1953, poet Robert Lowell wrote to his friend and fellow poet, Elizabeth Bishop:

“I guess you’ve heard about Dylan Thomas’s death. He died four days after a brain stroke which seems to have immediately finished his mind. The details are rather gorgeously grim. He was two days incommunicado with some girl on Brinnin’s staff in some New York hotel. Then his wife came … and tried quite literally to kill and sleep with everyone in sight. Or so the rumors go in Chicago and Iowa City. It’s a story that Thomas himself would have told better than anyone else; I suppose his life was short and shining as he wanted it—life, alas, is no joke.”

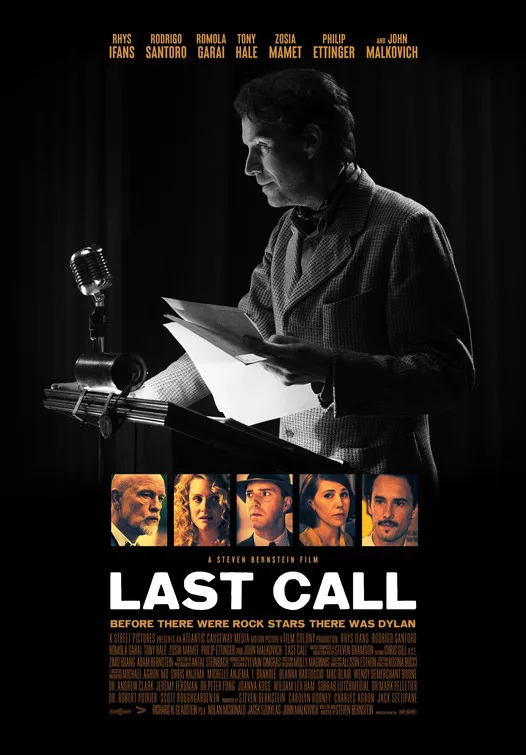

As the legend (most probably apocryphal) goes, Dylan Thomas’ final words before collapsing in the Chelsea Hotel were, “I’ve had 18 straight whiskies. I think that’s the record.” People who were actually there in the White Horse Tavern that day dispute this, but those mythical 18 whiskeys are the organizing principle of Steven Bernstein’s “Last Call,” with Rhys Ifans as the Welsh poet drinking his way into delirium, surrounded by a hooting crowd of admirers and concerned “friends.” This is well-trod ground (most recently, in 2014’s “Set Fire to the Stars“), perhaps because there’s something garish and hypnotic about Thomas’ death and those final words, in all their sickly bravado. “Last Call,” also written by Bernstein, takes the legend as truth, and expands on it, making Thomas’ march towards that 18th drink a deliberate piece of performance art. “Last Call”‘s original title was “Dominion,” after one of Thomas’ most famous poems, “And death shall have no dominion” (quoting St. Paul’s epistle to the Romans). “Dominion” is a far better title than the generic “Last Call,” but the problems here go beyond the title. Watching a man drink himself to death, seemingly on purpose, is a pretty tough whiskey to swallow, even if he is articulate and dramatic, even if he is a famous poet, and even if he is played with a shamanistic power by Rhys Ifans.

Dylan Thomas was always more shaman than poet, and his poetry readings were major events. He didn’t just have admirers. He had fans. He wasn’t just a well-known poet. He was a “star.” Like Anne Sexton was a star, like Edna St. Vincent Millay was a star: these poets crafted public personae, like movie stars do, and they wove spells over their audiences, in the same way Jim Morrison did, or Mick Jagger did. By the time period covered in “Last Call,” Thomas already felt the emptiness of much of what he was doing. He knew he was a ham. He felt there was something fraudulent in how things were going. He admitted it himself once: “I’m a freak user of words, not a poet.” In his mind, the American reading tours were cynical cash grabs, and he drank up all the profits anyway, leaving his wife and children at home in Wales, destitute. It was during one of these tours that Thomas stopped off in New York, to attend early rehearsals for a production of his verse play Under Milk Wood. He was already extremely unwell.

“Last Call” jumps around in time, and Bernstein switches up the styles, moving from desaturated color to black-and-white, bringing in fuzzy hallucinations and using rear-projection for some of the New York scenes. There’s a lot of cross-cutting between scenes and locations and times, moving from Thomas giving readings at different colleges, back to Wales, where his wife Caitlin (Romola Garai) writes increasingly furious letters, begging for money. Meanwhile, Thomas’ “handler” and eventual biographer John Malcolm Brinnin (Tony Hale) and Thomas’ cynical doctor Dr. Fenton (John Malkovich, who also produced), commiserate over what to do with their increasingly incapacitated client. Zosia Mamet plays Penelope, a young Vassar student, who’s booked Thomas to come and speak at her college (incurring the wrath of the administration, who consider Thomas a dangerous libertine. They’re not entirely wrong). Penelope loves Thomas with the passion of a fangirl, declaring to a friend, “I love everything about him. I’d have his child if he asked me to.” Her friend says, “You are joking.” She says, “Which part.”

All of these characters converge on Thomas as he holds court at the White Horse Tavern, being poured enormous shots of whiskey by bartender Carlos (Rodrigo Santoro), who has never heard of the words, “Okay, sir, I’m cutting you off.” The film is broken up with grim time-stamps—”10:00 a.m.,” “4:00 p.m.”—showing Thomas’ progression into that good night. Caitlin, whose behavior was even more scandalous than her husband’s, shows up in a hallucination, “Pleasantville“-style, she in color surrounded by black-and-white. Sometimes there are flashbacks to Thomas’ childhood, a small boy running through wide snow fields. It’s a very busy film, stylistically.

Most of the actors do very well in what are fairly thankless roles. Hale stands on the sidelines, watching helplessly as Thomas drinks himself to death, and also wondering if his idol has had a chance to read his manuscript yet. (One wants to say to Brinning; “Why are you giving a man on a bender the only existing copy of your manuscript? Have you ever met an alcoholic before?”) The “Caitlin” sections are not all that successful, particularly since Garai is forced to read the letters she’s writing out loud. This device would work beautifully onstage. On film it looks phony and presentational.

Ifans, who recently played Captain Cat in a film adaptation of Thomas’ Under Milk Wood, is glorious in the role, and the film is filled with shots of him reading Thomas’ poetry during the preceding American tour: “Fern Hill,” “A Child’s Christmas in Wales,” “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.” Audio clips of Thomas reading his work give a feel for the spell he wove on his audiences. Thomas didn’t speak so much as he sang; he didn’t articulate so much as he rode the waves of sound he produced. Ifans captures Thomas’ thrumming recitative style, which was more about creating a mood than conveying meaning. Bernstein’s repeat shots of college girls staring up at Ifans, agog, rapt, are eloquent. This is more like the spoken-word poetry jams of later decades, the coffee-house folk-music culture of the 1960s. No wonder college kids were caught up in Thomas’ magic. (It has always struck me as interesting that Thomas’ most famous poem, “Do not go gentle into that good night” was a villanelle, one of the most rigorous rules-based forms in existence. When Thomas wanted to, he could submit to the rules, and he did it brilliantly!)

Too late in the game, the film suddenly gets fascinating, albeit in an esoteric way, as Carlos the bartender moves from out behind the bar and takes over the narrative. Carlos reveals hidden depths, first in a spontaneous tango with the disillusioned Penny, and then in a brutal monologue where he cuts Thomas down to size. All along, Carlos has pretended to not be familiar with Thomas’ work. Now it is clear Carlos knows it very well and finds it extremely wanting. He says, echoing many of Thomas’ critics, that Thomas “mistakes sound for substance.” Then he says, and it’s the killshot, “You and I both know there’s nothing there but the cadence of the language. Not Auden. Not Yeats.”

Is Carlos real? Or is he Thomas’ worst fears made manifest? In his essay “Dylan the Durable,” Seamus Heaney wrote of “Do not go gentle into that good night,” “This is a son comforting a father; yet it is also, conceivably, the child poet in Thomas himself comforting the old ham he had become; the neophyte in him addressing the legend; the green fuse addressing the burnt-out case.”

This is an intriguing thing to consider when you read the poem, and it’s something Ifans appears to understand intimately in his performance: The emptiness behind all those words, those freaky words that came so easily to him, that added up to so little.

If you find Thomas fascinating, as I do, then there’s a lot here to chew on. But “Last Call” is a pretty grim watch. Not “gorgeously grim.” Just grim, end-stop.