Hoffman is one of those people with the bad luck to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. He’s a scientist, he has a clean police record, but when the police get into a violent scuffle he gets involved and is shot in the head. Reinhard Hauff’s “Knife in the Head” is about what happens then.

The first questions concern life and death. He may not live, and we gather that the police would be just as happy if he doesn’t. There is an attempt to frame him for a crime, in order to justify the police violence against him. To the astonishment of those who know him, he’s suddenly portrayed as a radical in the newspapers, and then embraced as a hero by leftist groups.

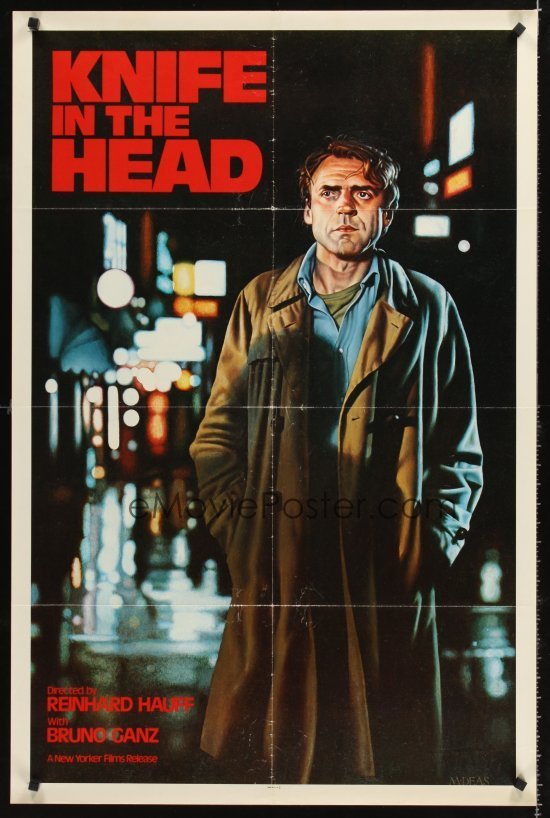

Meanwhile, his wife receives the bad news that, following brain surgery, he’s going to have to start all over to learn how to feed himself, to talk, to walk. The film’s middle passages are mostly concerned with this arduous process, as he smears oatmeal all over his face and learns to live with the humiliation of being an adult with a baby’s motor skills. Bruno Ganz, one of the most powerful of the new generation of West German actors, plays this material with a rough, simple dignity.

In a larger sense, Hauff, a young West German director, is using Hoffman’s helplessness as a metaphor for his own society in the 1970s. Terrorism has become a fact of life in West Germany, after the Bader-Meinhoff Gang and the attack on Israeli athletes during the Munich Olympics. The population in general has been something like Hoffman: Disengaged, noncombatant, suddenly caught in the cross-fire and forced to relearn its own political beliefs an agonizing step at a time.

“Knife in the Head” functions then, in two ways at once. It’s a meticulous and carefully observed portrait of a gravely handicapped professional man learning all over again how to lead his life. And it is also the record of how he reacts to his own startling realization that innocent people do get shot, that the authorities do lie, that social democracy does not always set the rules under which things happen in a “civilized” society.

Yet “Knife in the Head” isn’t a straightforward leftist political tract; it’s much more subtle than that, and if it has a position, it’s closer to despair than to radical reform. One of the film’s most nihilistic scenes involves a confrontation between Hoffman, who is now able to limp around fairly well although his arm is still numb, and the policeman who has been persecuting him since the beginning.

Hoffman prepares himself fatalistically for a confrontation … but his moment has passed, he learns, and the police no longer have an official interest in him. Now they’re looking for someone else. That is the greatest affront yet: Handicapped for life, he is now cast aside as a manufactured enemy of the state, and is free to live and suffer as best he can.