Everybody’s sin is nobody’s sin. And everybody’s crime is no crime at all.

Talk like that made people really mad at Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey. When his first study of human sexual behavior was published in 1947, it was more or less universally agreed that masturbation would make you go blind or insane, that homosexuality was an extremely rare deviation, that most sex was within marriage and most married couples limited themselves to the missionary position.

Kinsey interviewed thousands of Americans over a period of years, and concluded: Just about everybody masturbates, 37 percent of men have had at least one homosexual experience, there is a lot of premarital and extramarital sex, and the techniques of many couples venture well beyond the traditional male-superior position.

It is ironic that Kinsey’s critics insist to this day that he brought about this behavior by his report, when in fact all he did was discover that the behavior was already a reality. There’s controversy about his sample, his methods and his statistics, but ongoing studies have confirmed his basic findings. The decriminalization of homosexuality was a direct result of Kinsey’s work, although there are still nine states where oral sex is against the law, even within a heterosexual marriage.

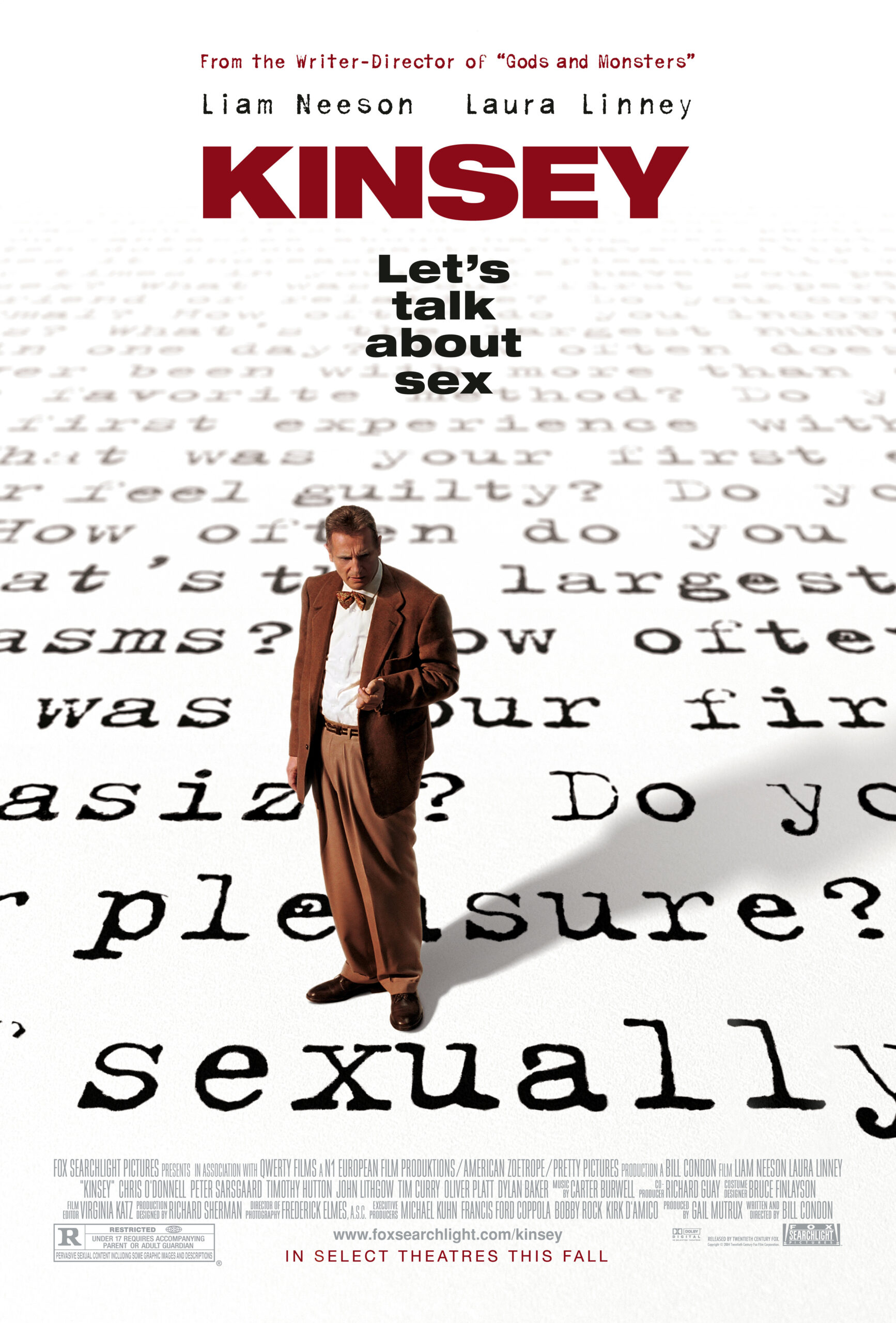

“Kinsey,” a fascinating biography of the Indiana University professor, centers on a Liam Neeson performance that makes one thing clear: Kinsey was an impossible man. He studied human behavior but knew almost nothing about human nature, and was often not aware that he was hurting feelings, offending people, making enemies or behaving strangely. He had tunnel vision, and it led him heedlessly toward his research goals without prudent regard for his image, his family and associates, and even the sources of his funding.

Neeson plays Kinsey as a man goaded by inner drives. He began his scientific career by collecting and studying 1 million gall wasps, and when he switched to human sexuality he seemed to regard people with much the same objectivity that he brought to insects. Maybe that made him a good interviewer; he was so manifestly lacking in prurient interest that his subjects must have felt they were talking to a confessor imported from another planet. Only occasionally is he personally involved, as when he interviews his strict and difficult father (John Lithgow) about his sex life, and gains a new understanding of the man and his unhappiness.

The movie shows Kinsey arriving at sex research more or less by accident, after a young couple come to him for advice. Kinsey and his wife Clara McMillen (Laura Linney) were both virgins on their wedding night (he was 26, she 23) and awkwardly unsure about what to do, but they worked things out, as couples had to do in those days. Current sexual thinking was summarized in a book called Ideal Marriage: Its Physiology and Technique, by Theodoor Hendrik van de Velde, a volume whose title I did not need to double-check because I remember so vividly finding it hidden in the basement rafters of my childhood home. Van de Velde was so cautious in his advice that many of those using the book must have succeeded in reproducing only by skipping a few pages.

One of the movie’s best scenes shows Kinsey giving the introductory lecture for a new class on human sexuality, and making bold assertions about sexual behavior that were shocking in 1947. His book became a best seller, Kinsey was for a decade one of the most famous men in the world, and he became the target of Congressional witch-hunters who were convinced his theories were somehow linked with the Communist conspiracy. That patriotic middle Americans had contributed to Kinsey’s statistics did not seem to impress them, as they pressured the Rockefeller Foundation to withdraw its funding. One of the quiet amusements in the film is the way Indiana University President Herman Wells (Oliver Platt) wearily tries to prevent Kinsey from becoming his own worst enemy through tactless and provocative statements.

The movie has been written and directed by Bill Condon, who shows us a Kinsey who is a better scientist than a social animal. Kinsey objectified sex to such an extent that he actually encouraged his staff to have sex with one another and record their findings; this is not, as anyone could have advised him, an ideal way to run a harmonious office. Kinsey didn’t believe in secrets, and he brings his wife to tears by fearlessly and tactlessly telling her all of his. Laura Linney’s performance as Clara is a model of warmth and understanding in the face of daily impossibilities; she loved Kinsey and understood him, acted as a buffer for him, and has an explosively funny line: “I think I might like that.”

Kinsey evolved from lecturing to hectoring as he grew older, insisting on his theories in statements of unwavering certainty. His behavior may have been influenced by unwise use of barbiturates, at a time when their danger was not fully understood; he slept little, drove himself too hard, alienated colleagues. And having found that people are rarely exclusively homosexual or heterosexual but exist somewhere between zero and six on the straight-to-gay scale, he found himself settling somewhere around three or four. The film’s director, Bill Condon, who is homosexual, regards Kinsey’s bisexuality with the kind of objectivity that Kinsey would have approved; the film, like Kinsey, is more interested in what people do than why.

The strength of “Kinsey” is finally in the clarity it brings to its title character. It is fascinating to meet a complete original, a person of intelligence and extremes. I was reminded of Russell Crowe’s work in “A Beautiful Mind” (2001), also the story of a man whose brilliance was contained within narrow channels. “Kinsey” also captures its times, and a political and moral climate of fear and repression; it is instructive to remember that as recently as 1959, the University of Illinois fired a professor for daring to suggest, in a letter to the student paper, that students consider sleeping with each other before deciding to get married. Now universities routinely dispense advice on safe sex and contraception. Of course there is opposition, now as then, but the difference is that Kinsey redefined what has to be considered normal sexual behavior.