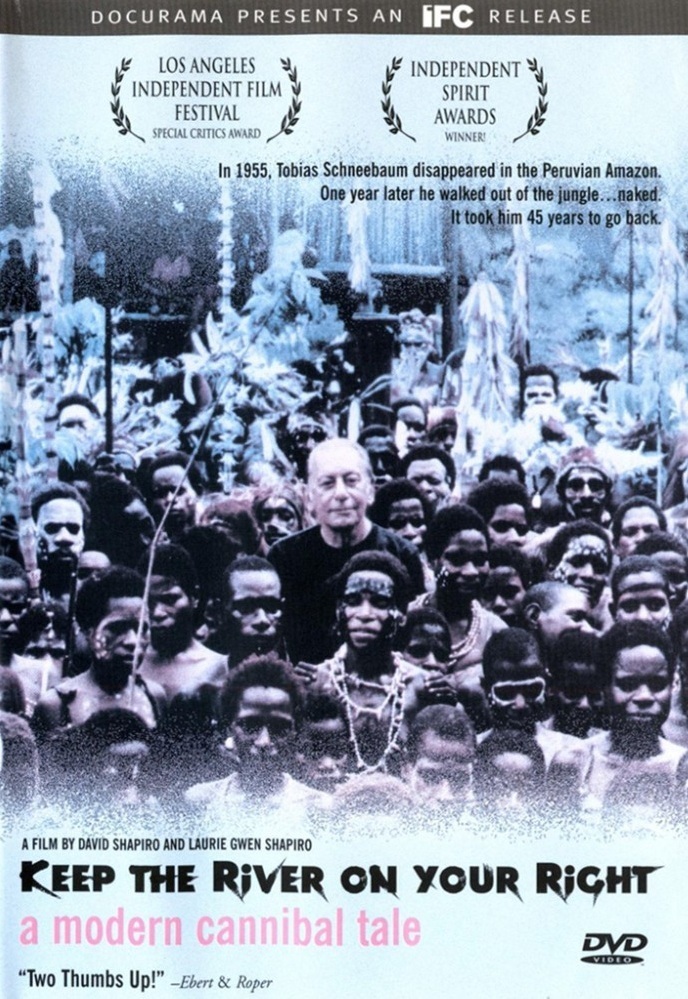

Ifc Films Presents A Documentary By David Shapiro And Laurie Gwen Shapiro. Running Time: 93 Minutes. Rated R (Cannibalism).

In the mid-1950s, a New York artist and anthropologist named Tobias Schneebaum walked into the rain forests of Peru, planning to paint some pictures there. His geographical knowledge was limited to the advice: Keep the river on your right. A year later, he walked out of the jungle naked, covered with body paint, having found and lived with an Indian tribe for a year.

At some point during that year, the tribe went on a raid, killed enemies and ate them. Schneebaum joined them in consuming human flesh. “Didn’t you try to stop them?” someone asks him in this documentary. It is the kind of question asked by a person who has never had to live with cannibals, on their terms.

Schneebaum is not the kind of man you would immediately think of in connection with this adventure. Seventy-eight when the film was made, he is a homosexual aesthete who lectures on art and works as a tour guide on cruise ships. Yet his adventures were not limited to Peru, and in the extraordinary documentary “Keep the River on Your Right: A Modern Cannibal Tale,” he also revisits the jungles of New Guinea, where he lived with a tribe, took a male lover and has a reunion with his old friend. Many years have passed, but the friend accepts him as warmly as if he’d been away for a week or two.

The visits to his old homes in New Guinea and Peru are not without hazards. Schneebaum isn’t worried about jungle animals or diseases, but has more practical concerns on his mind, like breaking a hip: “If I slip on the mud, I’ve had it.” The movie is the work of a brother and sister, David Shapiro and Laurie Gwen Shapiro, who learned about Schneebaum and became determined to make a movie about him. It is a story he has been telling for years; he wrote a memoir about his adventures, and we see clips of him chatting about the book with Mike Douglas and Charlie Rose. He also, I imagine, gets good mileage out of his stories on those cruise ships, although he is not particularly eager to discuss cannibalism, and we sense pain that his dry, laconic style tries to mask. Asked how people taste, he answers shortly, “I don’t remember.” At another point, in another context, he observes, “I kind of died. Something I had that was made of me, and then it was gone after the Peruvian experience.” Can we speculate that he penetrated so close to the fault line of human existence that he lost the unspoken security we walk around with every day? Things may get bad for us, even hopeless, but we will not be naked in the jungle, face to face with life’s oldest and most implacable code, eat or be eaten. Schneebaum doesn’t strike us as the Indiana Jones sort. He didn’t go into the jungle as a lark. Whatever happened there, he prefers to describe in terms of its edges, its outside.

The sexuality he encountered in New Guinea is another matter, and there he cheers up. The men of the tribe he lived with have sex with both men and women and consider it natural. We sense this is not the kind of sex people go looking for in big Western cities, but more of a pastime and consolation among friends. There is a certain shy warmth in the reunion with his former lover, but subtly different on Schneebaum’s side than on the other man’s, because sex between men means something different to each of them.

Schneebaum could probably develop a stand-up act based on his adventures, but he is more of a muser and a wonderer. “You’re there to study them, not to play with them,” he says sharply at one point. I met him at the 2000 Toronto Film Festival, where in interview and question sessions, he answered as if he were a teacher or a witness, not a celebrity. We get glimpses of his earlier life in Greenwich Village (former neighbor Norman Mailer remembers him as “our house homosexual–terrified of a dead mouse”), and learn something of his painting and his books.

But mostly we are struck by the man. “Keep the River on Your Right” could have been quite a different kind of film, but the Shapiros wisely focus on the mystery of this man, who was spectacularly ill-prepared for both of his jungle journeys, and apparently walked away from civilization prepared to rely on the kindness of strangers. Perhaps it was his very naivete that shielded him. The cannibals obviously had nothing to fear from him. Today, we learn, they no longer practice cannibalism, and indeed are well on their way down the capitalist assembly line, shedding their culture and learning to eat fast food. Tobias Schneebaum was not only their first visitor from “civilization,” but their most benign.

Note: The flywheels at the MPAA ratings board have given this sweet and innocent movie an R rating, explaining “cannibalism.” Yes, but the cannibalism is not seen, only discussed. How can this film and “Freddy Got Fingered,” with Tom Green biting a newborn baby’s umbilical cord in two, deserve the same rating?