There’s this thing for rodeo movies all of a sudden. Mostly they seem to have the same plot – the veteran rodeo star making his comeback against the meanest bull on the circuit. They have the same visual feeling, too, with lots of dusty roads and pickup trucks and rodeo footage cleverly edited to make it took like the star is really there in the arena. So our only choice is which rodeo cowboy we want to see.

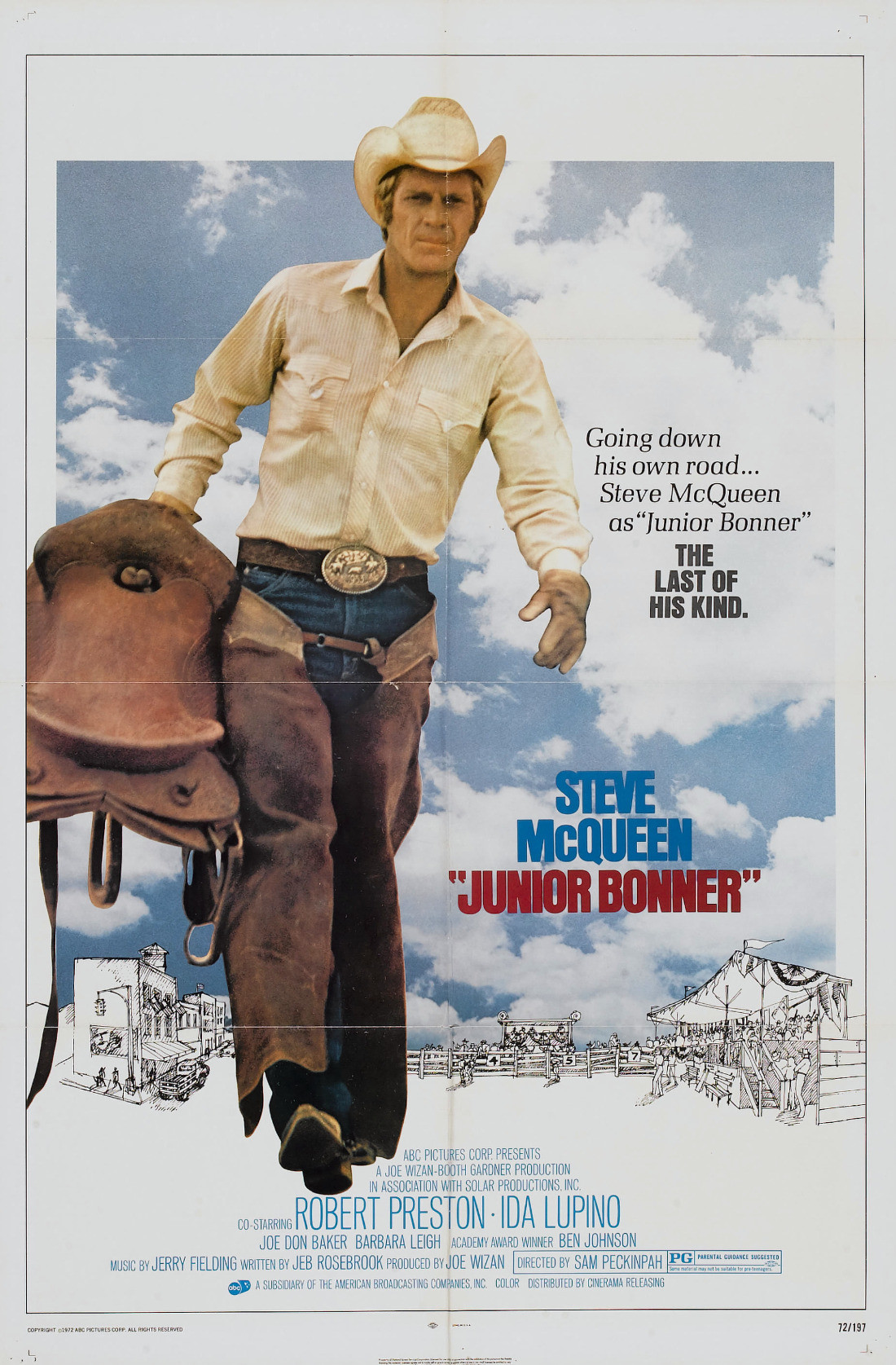

There was Cliff Robertson in “J. W. Coop,” and then James Coburn in “The Honkers,” and now Steve McQueen in “Junior Bonner.” Of the three, “Junior Bonner” has the most distinguished director: Sam Peckinpah, who has led previous excursions into the West in “The Wild Bunch,” “Ride the High Country” and “The Ballad of Cable Hogue.” The first two rodeo movies were directorial debuts by actors: Robertson himself and the late Steve Ihnat.

The surprising thing is that Peckinpah comes off so badly in this company. The best of the rodeo films so far is, clear and away, “J. W. Coop.” It also does the best job of getting inside its rodeo cowboy, instead of just plastering him over with all kinds of prefab plot devices. J. W. Coop was a man just out of prison, who had kept in shape with the prison rodeo and was now trying to make a modest comeback. As played by Robertson, and as surrounded by a crowd of ordinary rodeo people, he was a person whose hungers we could understand even if we didn’t give a damn about the rodeo.

“The Honkers” was more conventional and was padded out at excessive length by too many soft-focus lyrical interludes with dumb songs. Still, there was Lois Nettleton as Coburn’s strong and yet suffering wife, and Slim Pickens in a really fine character performance as Coburn’s oldest friend.

Seen with these two earlier films in mind, “Junior Bonner” becomes a flat-out disappointment, despite Peckinpah’s track record and his proven ability to elegize the West. It’s hard, at first, to figure out what goes wrong. The movie is populated with good performances.

The McQueen character (who is the kind of guy people just naturally call “Junior”) both admires his father and remains a little in his shade. Robert Preston, as the father, is one of the best old coots in the movies since Walter Huston. Ben Johnson, fresh from his triumph in “The Last Picture Show” and playing a rodeo promoter, reminds us again that a lot of great character actors languished in the backgrounds of John Ford’s Westerns. And there is Ida Lupino, her first movie since 1966 and looking beautiful and resourceful.

There are sustained stretches of great Peckinpah moviemaking, too. He gives us a genial tavern brawl that seems to be carried out mostly for the exercise. And then he has the long-estranged Preston and Miss Lupino sneak out the back door, engage in some nostalgic and yet suspicious memories, and then finally (in one of the most tender love scenes I can remember) go upstairs to one of the rooms over the saloon to make love for the first time in years.

And yet the movie simply never comes together and works as a whole. The material is terribly thin. A story line is introduced (McQueen, aiming for the mean bull, is also present at a moment of family crisis which has his dippy brother selling off the family land for mobile homes). But nothing much is resolved, and the movie finally loses so much tension and movement that when McQueen finally does conquer the bull we wonder why it took him so long.