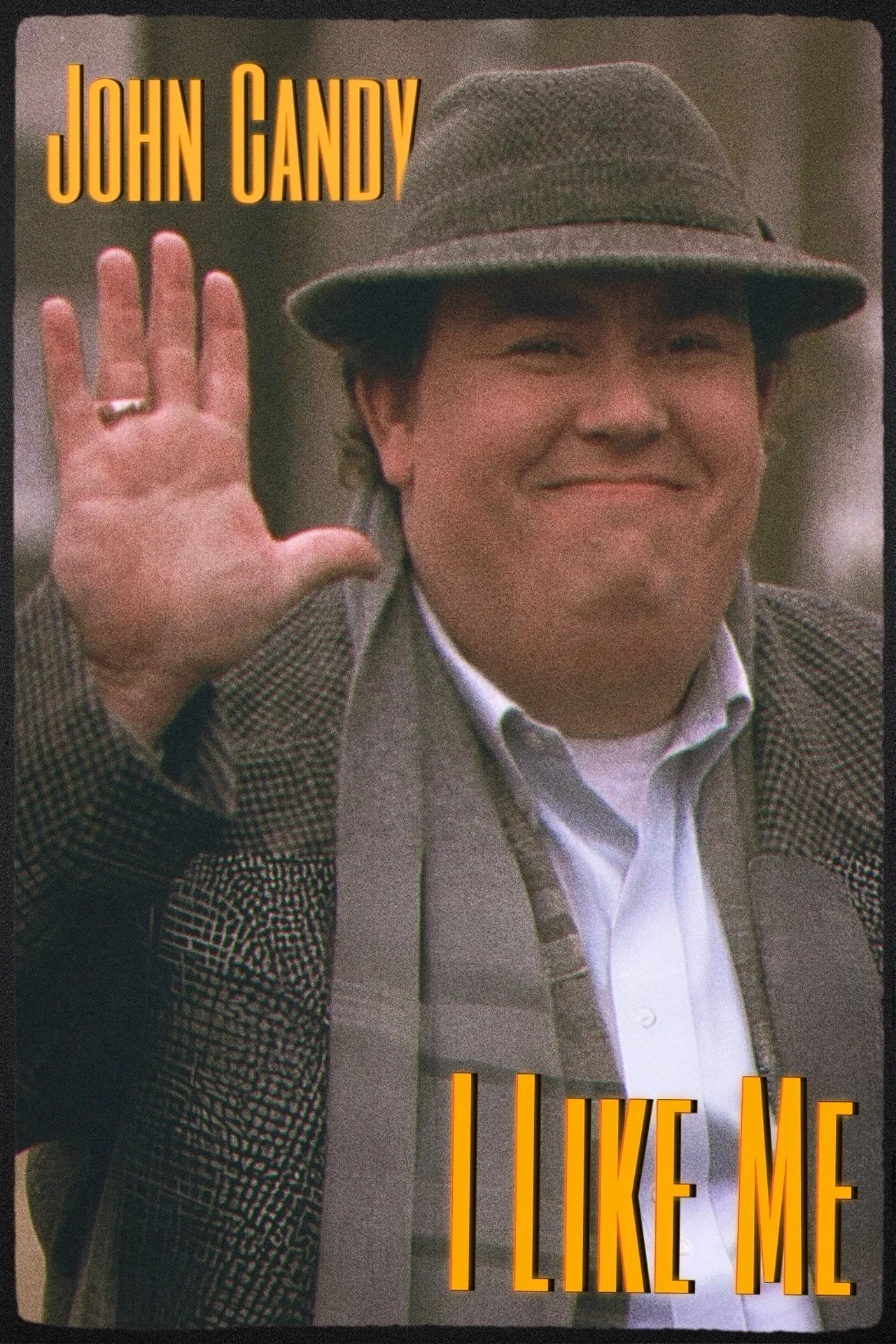

In the very first, pre-credits interview of Colin Hanks’s “John Candy: I Like Me”—a perfectly acceptable bio-documentary filled with entertaining clips and beloved entertainers telling heartwarming stories—his friend and frequent co-star Bill Murray poses the conundrum of telling Candy’s story: “I wish I had some bad things to say about him.” Candy, the gregarious star of “SCTV,” “Uncle Buck,” and “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” (among many others), was famously a mensch, a good-hearted guy who gave freely of his time and talent, was loyal to his friends, and knew every member of every crew on every show by name; that reputation has only spread, and expanded, in the years since his untimely passing in 1994 at only 43 years old. And so that becomes the biographer’s question: was he really a saint, or was there a darker side underneath?

I have spent some time grappling with this. Full disclosure: I spent six months back in 2022 researching a book biography of Mr. Candy, which was ultimately abandoned due to lack of interviews (most of those who knew and worked with him were participating in this film). But that question had already reared its ugly head—because everyone has their demons, so what were his? Well, we’re certainly not going to find out in an official, family-authorized (his widow and children are all credited as co-executive producers) bio-doc directed by the son of a frequent co-star and friend. So yes, it’s hagiography. But that doesn’t mean it can’t have some nuance.

What’s undeniable is the breadth and depth of the material made available by their participation. We’re treated to copious home videos, rare outtakes from his movies and footage from his stage performances, family photos, the works. Everyone you want to hear from shows up: his Second City and SCTV co-stars, his film collaborators, comic giants he inspired, the director’s dad.

To his credit, the junior Hanks makes a genuine effort to delve in to Candy’s psychology—to understand what drove him. Up top, we see Candy and Dan Aykroyd in a “Citizen Kane” parody, and if there’s a Rosebud in Candy’s life, it’s the death of his 35-year-old dad on John’s fifth birthday (a touch that most dramatists would wave off as too on-the-nose). And so the young boy became the patriarch, and through the rest of his life, the provider and the giver for his family and everyone around him. But moreover, he was haunted by a fear of death and tragedy—a sense, as Tom Hanks put it, that “he is living on borrowed time and he was gonna go away, just like his father did.”

That’s all affecting, and to its credit, “I Like Me” notes that Candy would and could hold a grudge, and was sometimes impatient with those around him, particularly as the pressures of stardom mounted and he attempted to stay grounded (though that’s all fairly typical showbiz bio stuff). Perhaps the most compelling material, genuinely specific to his story, is the weightism he experienced while in the public eye, and how painful it was for him. You can see his discomfort when it comes up in interviews (“People treat ya differently sometimes, and it hurts,” he explains, simply but heartbreakingly) and you hear from those around him how he tried to balance health with the public persona he’d cultivated, of “Johnny Toronto,” the jaunty, carefree Falstaff figure.

That material lands, as do many of the interviews; it’s hard not to get swept up in the excitement of the “SCTV” years, and while all of his co-stars have stories to tell and praise to impart, Macaulay Culkin’s memories are particularly powerful and poignant (especially if you know his whole story). And the section surrounding his death is like a punch in the gut, so sad and moving, capped by a devastating photo montage of candid pictures of Candy with friends, family, but mostly with fans—whom he treated like they were friends and family too.

But many of the editing choices are painfully predictable (particularly the scene-setting historical sections early on), Tyler Strickland’s score is unbearably treacly, and some of the structuring choices are downright baffling (why on earth is 1987’s “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” introduced as if it were a follow-up to 1989’s “Uncle Buck”?). Most importantly, little to no interest is paid to Candy’s considerable growth as an actor over the course of his career—particularly in the last few years of his life, when he was supplementing favor-for-a-friend slop like “Nothing But Trouble” with semi-dramatic and dramatic turns in “Only the Lonely” and “JFK,” respectively.

The Margaret Herrick Library in Beverly Hills now houses Candy’s considerable archive of papers—old scripts, schedules, notes, fan letters. Most of his production screenplays are as clean and crisp as if they just came out of the photocopier, but I spent one afternoon there thumbing through his dog-eared screenplay for “JFK,” which he’d marked up with questions and notations from his dialect coach, and painstakingly underlined with specific words to emphasize in his dialogue. He was a real actor who took his craft seriously, and clearly saw a path ahead of him beyond broad comedy. That side of him is entirely absent from “John Candy: I Like Me,” and it makes one wonder what else is missing too. In the closing moments, a TV obituary describes him as “the actor with the heart of gold,” and unfortunately, this documentary—with all its resources and access—rarely goes much deeper than that.

This review was filed from the world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. It will be on Amazon Prime Video on October 10, 2025.