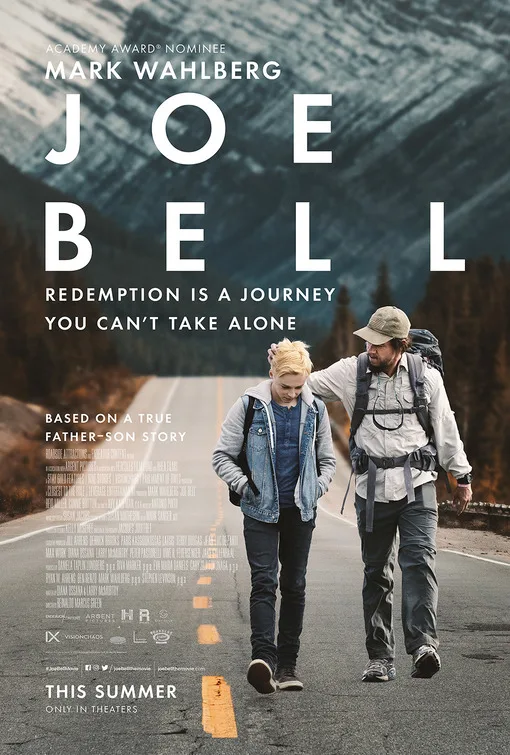

A star vehicle for producer-star Mark Wahlberg, whose involvement ironically complicates a film that would not exist without his participation, “Joe Bell” is based on the true story of a man who walked from La Grande, Oregon, to New York City in 2015 to raise awareness of bullying.

Bell was driven by the loss of his son Jadin, an openly gay 15-year-old who killed himself after months of being tormented by bigots at his high school. The dramatized movie version of this story is poised between no-budget indie-film intimacy and Hollywood bombast. The emphasis on the father’s grief often crowds out the suffering of Jadin, his mother, and other major characters (mainly in the first section, its weakest). As the movie, like its hero, trudges dutifully to its climax, there’s no shortage of unnecessary trickery in the telling (including a non-chronological structure, and the re-use of a particular cliche that was all over the place in the late 1990s and early aughts, and should be retired forever; you’ll know it when you see it). “Joe Bell” is carried by its good heart, generally strong performances, and superb direction by Reinaldo Marcus Green (“Monsters and Men“), and there are moments when you can see a stronger, more focused film struggling to escape the morass.

It’s frustrating to watch a movie that seems so unable to get out of its own way—all the more so because this is one of the last collaborations between the Oscar-winning screenwriting team of Diana Ossana and Larry McMurtry. Their classic drama “Brokeback Mountain,” likewise about sexual repression and persecution in the American heartland, now feels like a past-tense companion piece to “Joe Bell.” That attitudes don’t seemed to have changed much since Jack and Ennis had to hide their love away is a tragedy of another sort, and it’s touched upon in a scene at a gay bar where Joe has an awkward conversation with a drag performer, and a middle-aged gay man sitting across from Joe tells him that the social advances of the 21st century never left major cities.

Another source of frustration is Mark Wahlberg’s monotonous, at times listless performance, which would negatively impact the film even if the actor didn’t enter it carrying baggage similar to that of the bullies that drove Jadin to his death. As a Boston teenager in the ’80s, Wahlberg committed an array of hate crimes, and although he has made gestures in the direction of atoning for them—including apologizing to one of his victims and receiving forgiveness, and petitioning the governor of Massachusetts to have his records expunged—skeptics said it was too little, too late, and speculated that it was impelled by the Wahlberg family’s financial self-interest as owners of a chain of burger restaurants. “Joe Bell” does not appear to have been a response to a suggestion by the aforementioned forgiver that Wahlberg do a film warning about the evils of bigotry, although in that case the suggestion was that Wahlberg’s character be a racist rather than a homophobe (not that there’s never crossover).

Straining for a sort of epic naturalism, steely eyes flinching at the words of other characters, Wahlberg seems to be going for something in the vein of Heath Ledger in “Brokeback Mountain,” Bradley Cooper in “American Sniper,” and Clint Eastwood in, well, anything. He does not, as they say, have the range. Wahlberg stares into the middle distance, pushes a wagon filled with minimal provisions along dusty roads through flat northern states, and sometimes bursts into tears of sorrow, but he’s badly outclassed by his costars, particularly Connie Britton as Joe’s wife, Lola; Reid Miller as Jadin; Maxwell Jenkins as Joe, Jr., who would rather have his dad at home than out on the highway making a spectacle of himself; and Gary Sinise, who comes in at the end in a small but important role, and is so smashingly effective at communicating the pain of a reactionary man stumbling towards decency that you might imagine the film with Sinise as Joe. Sinise is too old to play the real Joe (who was 45 when he lost his son), but he has a gift for universalizing politically coded “heartland” characters that might otherwise seem as if they’re trying to flatter their intended audience.

Wahlberg often seems like he’s pandering these days, and he often comes across as pandering here, however sincere his intentions. Since the mid-aughts, he’s played so many soft-spoken, simple-but-strong men, often clad in either military uniforms or jean jackets and ball caps, that he’s turned into a human Budweiser commercial. The filmmakers seem to want “Joe Bell” to reach the kinds of guys who’d pay to watch Wahlberg punch and shoot people for Uncle Sam, apple pie, and fireworks, but would never consider sitting still for a poker-faced melodrama about a man who feels such remorse over his failure to stand up for his son when he was still alive that he’s turned himself into a modern Christ figure, pushing his sins in a wheelbarrow and telling everyone he meets that they need to be nicer.

Ossana and McMurtry are well-aware of the traps built into this kind of project, and have been sure to include a few lines that raise an eyebrow at Joe’s mission. Joe is clearly not a great communicator. He talks at people rather than to them, and avoids specifics that might explain why he’s there, and the reaction shots of his audiences make them seem like they’re listening out of respect for a man who has suffered, not because they want to understand his suffering. The difficulty of connection is the movie’s most rewarding theme. After Joe places a tolerance pamphlet on the table of a couple of homophobic bullies at a truck stop rather than confront them, another character points out the conundrum of his situation: guys like the ones in the diner are much more in need of hearing his message than the people who turn out to listen to it, and that there’s no easy way to reach them, much less get them to open their minds.

Such is the irony of all social message movies, stretching through “Gentleman’s Agreement” (anti-Semitism), “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner” (racism), “Philadelphia” (homophobia) and beyond. It’s naïve to think “Joe Bell” can escape it, although the straightforward characterizations, loving visual attention to rural landscapes, and mix of liberal and conservative signifiers has a Clint Eastwood-like hypnotic effect, drawing you into the fiction, and forcing the admission that most people are confounding and tend to contradict themselves. It’s easy to imagine characters from Eastwood’s heartland melodramas mingling with the Bell family.

Wahlberg’s star profile makes “Joe Bell” feel more Joe-focused than it actually is. The final stretch shifts the movie’s attention to Joe Jr. and Connie, and it appears to side with them in suggesting that Joe’s masochism is self-serving. They’re right, but his choice is comprehensible when you think about the strength of the conditioning he’s trying to break through. A placard at the end of the credits marks the movie as property of an LLC called The Bells of LaGrande, which would have been a better title than “Joe Bell,” and more reflective of the community nature of the loss depicted here.

The brilliant director, a young Black New Yorker, treats the film’s white, fifty-ish, probably-voted-for-Trump characters with unforced empathy, placing them within a redemptive framework of people struggling towards a state of grace that might never be achieved. It’s a bridge-building piece of Americana that doesn’t let anyone off the hook, although the closing upbeat/inspirational notes seem a bit odd when you look back on the story, which is mostly just astonishingly sad, a chronicle of missed cues and craven errors in judgment that snowball until karma snaps into place and everyone in the Bells’ orbit suffers unimaginable pain. You can see why the filmmakers went with a non-linear structure: if they laid the same events end-to-end chronologically, viewers would come away shaken to their core, and the film would make five dollars.

The widescreen images and sentimental music (by Jacques Jouffret and Antonio Pinto, respectively) are reminiscent of Michael Cimino’s “The Deer Hunter,” still the gold standard for films about American prisoners of machismo. Sublime moments of cosmic detachment allow the landscapes to dominate the characters, reducing them to specks in a panorama. The splendor of mountains, prairies, and rain-swept towns implicitly condemns the pettiness of hatred in every culture. When a world is this beautiful, the film seems to be saying, why would anyone act ugly?

Now playing in theaters.