It’s customary to be told to turn off all electronic devices before a press screening these days. But at a showing of “Jobs,” the directive felt somewhat disingenuous given that the biopic pays homage to the Silicon Valley visionary who turned us into a society of raging gadget addicts.

And would that we had the option to leave our precious glowing doo-dads on just this once, if only to offer occasional distraction from what amounts to a glorified TV movie that is to “The Social Network” what “Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy” is to “Citizen Kane.” Rather than attempting a deeper plunge behind the whys and wherefores of the elite business-model gospel according to Apple guru Steve Jobs and—more importantly—what it says about our culture, the filmmakers follow the easy rise-fall-rise-again blueprint familiar to anyone who has seen an episode of VH1’s “Behind the Music.”

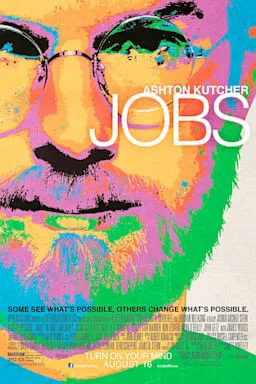

That judgment might be a tad harsh, especially since that dear boy Ashton Kutcher—considered a media savant of sorts himself for having hatched TV’s “Punk’d” and apparently beating CNN in a Twitter-follower race—really, really, REALLY tries to make us believe he is the Machiavelli of the Mac, the man who put the personal into computing. It isn’t an easy job to be Jobs, after all. He might have died in 2011 at age 56 but his presence will continue to loom large as long as there are Apple stores in malls. But Kutcher never totally recovers from an introductory scene set in 2001 when, in full Zen master mode, he introduces the iPod as “a music player…1,000 tunes in your pocket” to an auditorium filled with rapt acolytes.

You only get a teasing glimpse of Kutcher in puffy middle-age makeup, most likely because he looks a little ridiculous decked out in Jobs’s signature uniform: round wire-rimmed specs, gray beard and short-cropped hair, black mock turtleneck and Levis. And that is probably also a reason that the story then rewinds and instead focuses on Jobs from his college years to his early 40s. That way, the 35-year-old Kutcher can get away with his impersonation by simply varying his hair and beard length while regularly glaring with opportunistic intent.

In other scenes, the actor affectedly walks with a deliberate stooped gait, presumably emulating the real Jobs. Or maybe it’s just that the responsibility of bringing such a larger-than-life icon to life is weighing down the star of “Dude, Where’s My Car?”

But it isn’t really fair to lay the primary fault for this geek tragedy’s rather rote approach at the feet of its leading man. Feet, by the way, that are often unshod since, as we are shown numerous times, Jobs made a habit out of eschewing shoes—all the better to make a half-hearted Christ-figure analogy. The trouble is, we don’t find out much else about the guy’s motivations save for this take-no-prisoners drive to be the best in the biz. All the historic moments are duly ticked off, from Jobs freeing his mind with LSD and going to India in his college-dropout years to the supposed instant he came up with the corporate name of Apple. But while Jobs might have touted the iPod as a tool with a heart, this portrait of him is too often without a pulse.

Kutcher at least comes alive during the warts-and-all parts of the story. He isn’t half bad when being a bastard, such as when Jobs screams at anyone who defies his perfectionist aesthetic, doesn’t perform to his exacting standards or dares to steal an idea (too bad not more is made out of his feud with Microsoft’s Bill Gates). Failing to acknowledge the importance of multiple font options to this tech titan was apparently like waving a wire hanger in front of Joan Crawford.

Leading up to his eventual fall from grace at the company before his resurrection as its CEO, Jobs tends to behave like an insensitive self-serving ass, especially when he refuses to acknowledge his out-of-wedlock daughter or denies compensation to deserving friends who helped build the Apple empire back when it was a two-bit operation in his dad’s garage. But save for a few references of being abandoned by his birth parents and adopted later, the source of Jobs’s jerky behavior never is revealed.

Except for chubby supernerd Steve Wozniak — the most sympathetic and substantial secondary character thanks to the laidback affability of Josh Gad (Broadway’s “The Book of Mormon”) — whose idea to team a computer with a TV monitor changed both Jobs’s life and the world, those aforementioned pals are mainly ciphers. Recognizable performers in business suits crop up now and then, including James Woods, Dermot Mulroney, Matthew Modine and J.K. Simmons, but their talents are barely tapped.

As for the actresses who play the women in Jobs’s life, they fare the worst. Poor Lesley Ann Warren is briefly seen as Jobs’s adoptive mother but never heard.

Kutcher and his director, Joshua Michael Stern (“Swing Vote“), should have realized that when a movie presents its subject as a messiah of intuitive design who insisted that corners never be cut and compromises never struck, it should at least attempt to emulate such exacting standards. Instead, their version of Steve Agonistes too often just doesn’t compute.