Given the current state of international cinema, where titanic auteurs and formidable national cinemas in numerous countries largely belong to the realm of memory, it’s understandable that some artistically ambitious European directors would consciously refer back to what has been called the Golden Age of the Art Film (roughly the 1950s-’70s). Happily, the result of such retrospective awareness can be both impressive and invigorating.

Paolo Sorrentino’s “The Great Beauty” and Pawel Pawlikowski’s “Ida” are recent examples of films that look to cinemas past (of Italy and Poland, respectively) for inspiration yet are so full of their own power, originality and conviction that they make what was old look new again. Notably, both movies were not only critical favorites but big hits at art houses in the U.S. and elsewhere, suggesting that their appeal bridged cinephiles who recall the models they invoke, younger viewers who don’t, and regular moviegoers looking for something more interesting than Hollywood’s hackneyed fare.

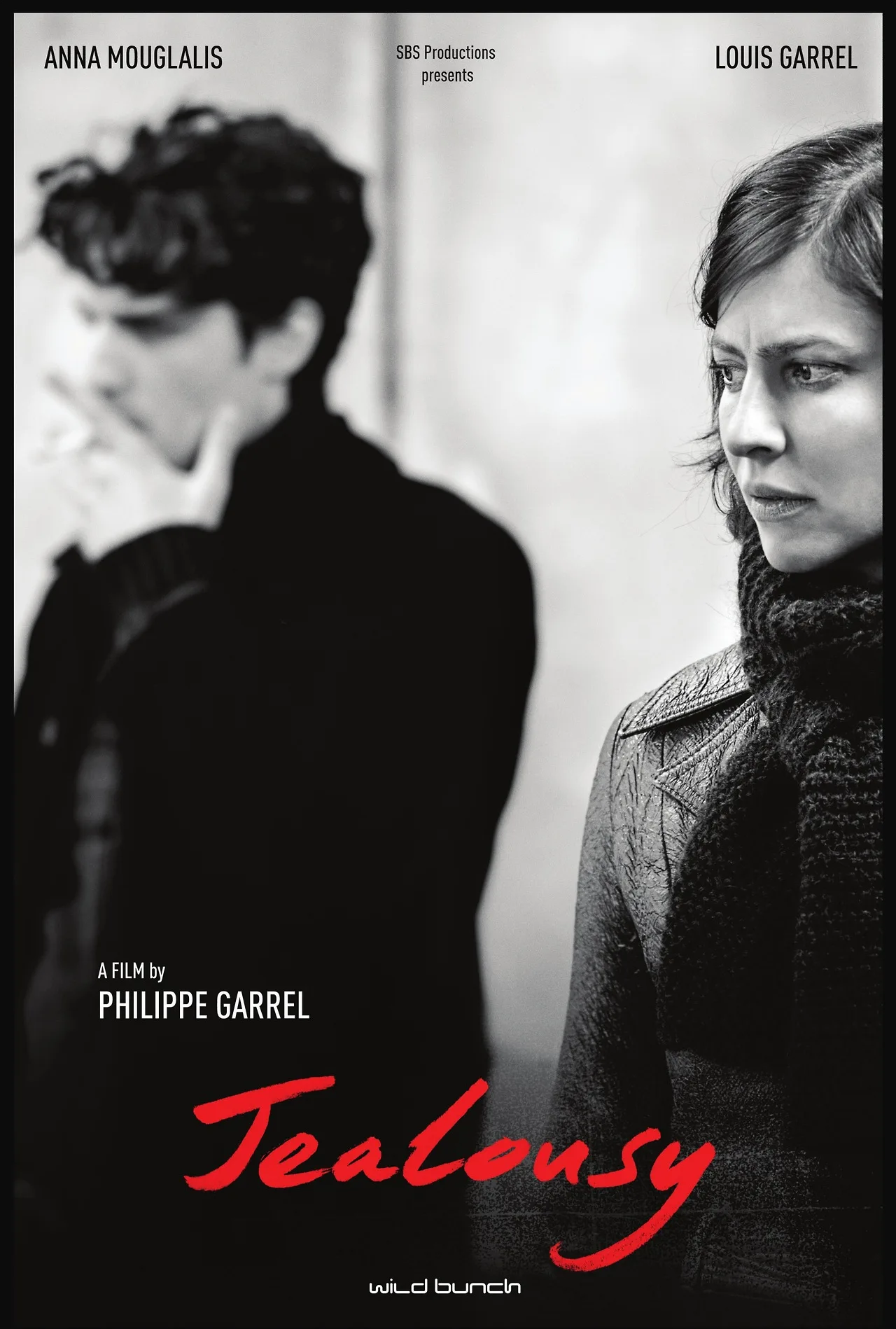

The other side of this coin is represented by Philippe Garrel’s “Jealousy.” Garrel, who has been making films for decades, is a favorite of highbrow critics in his native France, and his latest is touted as his most accessible film ever. So is he poised for, at long last, his big stateside breakthrough, as his coterie of U.S. admirers hopes? It’s hard to imagine he is, since “Jealousy” is the kind of slight, academic, self-satisfied exercise that preaches only to the converted.

Like every serious director to emerge from France since the early ’70s, Garrel has had to deal with the legacy of the French New Wave, of which he was just a bit too young to have been a part. Yet unlike French directors who’ve justifiably achieved international renown since–from the likes of Bertrand Blier and Maurice Pialat back when, to Olivier Assayas and Arnaud Desplechin more recently–he has remained an insular favorite, and “Jealousy” suggests that’s because he’s been content to operate within the boundaries left by the New Wave rather than push beyond them.

There is, of course, a large element of self-contradiction in this. The New Wave became a global sensation and changed film history by overthrowing an increasingly ossified set of cinematic conventions and establishing its own, more vital ones. To operate in the movement’s real spirit, then, would be to “make it new” yet again, rather than to imitate what was new 50 years ago, as Garrel does.

His bonds to the past are indicated by the fact that over his career Garrel has worked with three cinematographers who became legendary for their work with the New Wave: Raoul Coutard, William Lubtchansky and Willy Kurant. Kurant, who is 80, shot “Jealousy” in an elegant black and white (itself an indicative choice on Garrel’s part) that recalls Godard’s “Masculine/Feminine” and other films he shot a half-century ago.

Indeed, watching “Jealousy” you get visual echoes not only of Godard’s work but also of canonical films by Truffaut, Rivette, Rohmer, Eustache and other directors. What you don’t get is any sense of an aesthetic post-dating 1972.

Garrel’s strict allegiance to the stylistic tropes of decades past is matched by a similar penchant on the thematic level. Like a zillion other French films, “Jealousy” concerns the travails of l’amour and centers on a romantic trio of very attractive young people. The story begins when Louis (Louis Garrel) leaves his partner Clothilde (Rebecca Convenant) and their young daughter Charlotte (Olga Milshtein, whose performance is the film’s one breath of fresh air) to move in with his new love, Claudia (Anna Mouglalis). Both Louis and Claudia are actors, and impecunious, but he’s got work and she doesn’t. After spending some time with Claudia, it’s far easier to glean why no one will hire her than to understand why Louis doesn’t see that she’s a man-eater who’ll break his heart.

That last sentence perhaps should have been preceded by a spoiler alert, except that “Jealousy” is one of those films whose dramatic apex can, like Mont Blanc, be spied from ten miles off. Louis betrays Charlotte and is eventually betrayed by Claudia, who’ll trade in one boyfriend for another if it means a getting a bigger apartment (such are the cruelties of materialism, folks!). All of which seems as predictable and trite as it is obviously true to life and sincere.

As certain French critics began observing decades ago, the characteristic sin of French filmmakers is their over-reliance on naturalism, the sense that having things on the film’s surface (photography, the way characters are drawn, the performances embodying them) appear meticulously lifelike is more important than having something profound or original to say. That’s certainly the case with “Jealousy.” Garrel may not tread a single inch of new territory thematically, but the film’s staging (most scenes are done in a single take), its descriptions of its characters’ behavior and the actors’ performance are all accomplished with a steady, understated expertise.

And yet some of the old phoniness partly overthrown by the New Wave remains. Consider Louis Garrel, now making his fifth film with his dad. Louis is perhaps the only French actor more notable for his hair than his talent. His hair is spectacular, a glorious thicket of dark, upward-swept curls and tangles. It’s a mess so perfect, and Byronic, you can’t help but wonder how much time the hair-dresser spends on him before the camera rolls. There’s one shot where Louis and Anna Mouglalis are facing each other, and both are backlit, and the effect is so striking you almost regret there’s no Oscar for coiffures.

For Philippe Garrel, the film is a family affair in more than one sense. As it happens, son Louis is playing a character based on his own grandfather, who left Philippe’s mom for another woman. Perhaps making “Jealousy” thus comprised a bit of group therapy for the Garrels, and no doubt it would have been cheaper than psychoanalysis for all concerned. But like much about the film, these autobiographical elements will be of far greater interest to the director and his cult than to filmgoers at large.