James Burns overcame a life of crime and incarceration as a teenager to reinvent himself as a college-educated poet. His reckless youth and road to redemption are the subject of “Jamesy Boy,” a film with a message of inspiration, to be sure, but not much in terms of innovation.

Brothers Trevor and Tim White clearly mean well with their first feature. Trevor, the older of the two, directed and co-wrote the script (with Lane Shadgett), while Tim serves as one of the producers. Growing up in Annapolis, Md., they both knew of Burns’ troubled past and persuaded him to let them tell his story on screen.

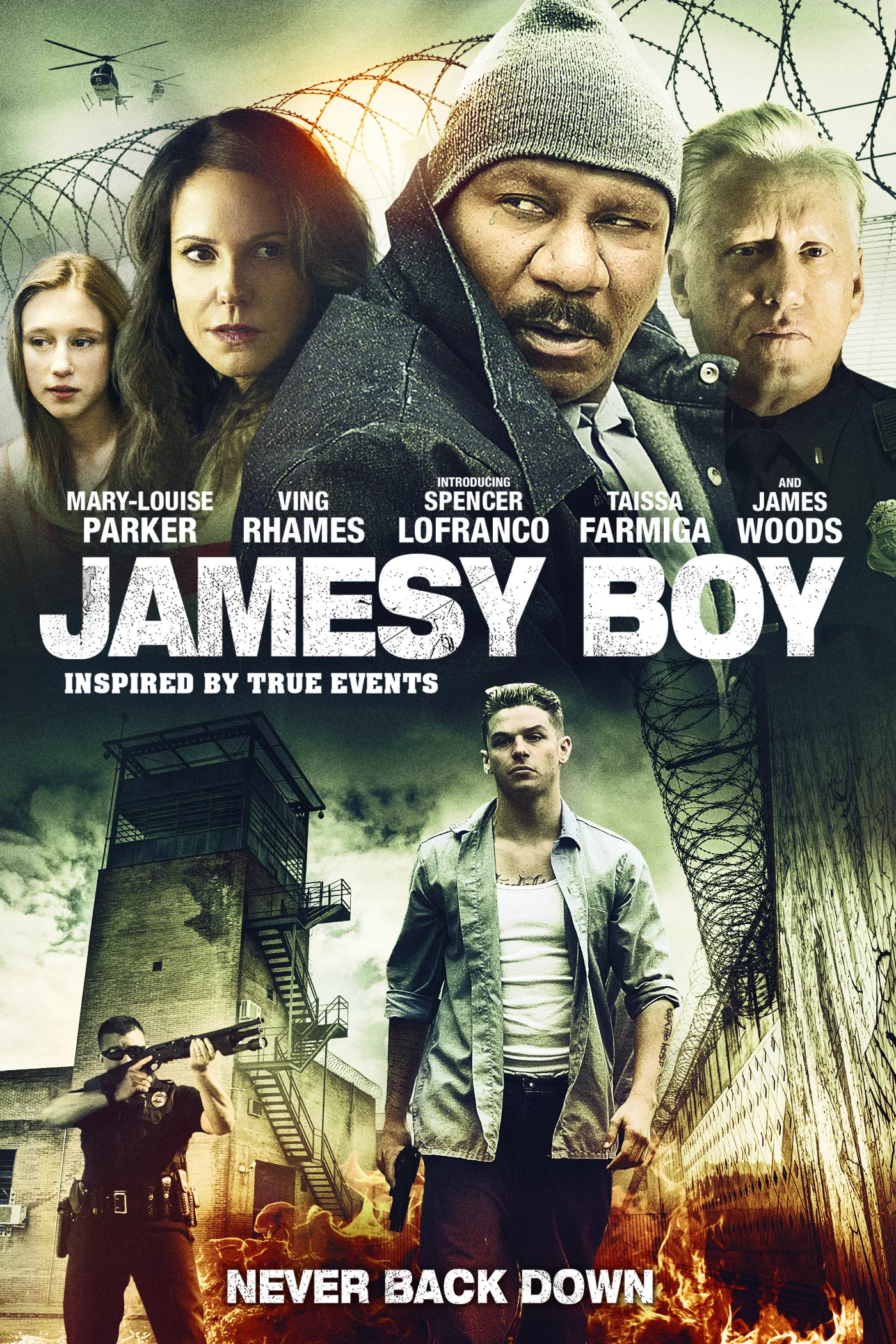

Trevor White shows some decent instincts and has assembled a impressive supporting cast (Ving Rhames, Mary-Louise Parker, Taissa Farmiga, James Woods). But he hits all the notes you’d expect in this type of uplifting tale: rebellion and debauchery, followed by run-ins with thugs and brushes with death, followed by time behind bars – where more run-ins with thugs and brushes with death await – and finally a chance to prove he can turn his life around. “Jamesy Boy” could play on a scared-straight double feature this week with the similarly formulaic “Life of a King,” starring Cuba Gooding Jr. as an ex-con who mentors wayward youth through chess.

The main problem, though—besides the obviousness of the trajectory—is that handsome, fresh-faced newcomer Spencer Lofranco is never terribly convincing when James is supposed to be at his most depraved and self-destructive. He’s got a bit of a young Tom Hardy to his look, and some young Mark Wahlberg to his tough-guy presence, but he’s not threatening or dangerous enough. He’s like a kid playing dress-up and doing the James Cagney, you-dirty-rat bit. (And the Toronto native’s Canadian accent too often betrays him.)

When we first see James, he’s lying face-down on the ground outside a prison bus while a corrections officer beats him in front of all the other inmates for picking a fight. “Jamesy Boy” then flashes back three years earlier, when he was only 14 and already wearing an ankle bracelet because of his long rap sheet. His single mother (an exasperated, straight-talking Parker) fights to place him in a public school, but administrators deem him too much of a risk.

In no time, he’s getting high, staying out late and robbing the nearby convenience store. Among his cohorts is the seductive bad-girl Crystal (Rosa Salazar), who introduces him to Roc (Michael Trotter), the local gang leader. The one positive force in his life is Farmiga’s Sarah, the daughter of the convenience store owner and its part-time clerk. Their quiet moments together are the film’s best. Their vulnerability with each other and their shared yearning to get the hell out of this nowhere town ring true.

“Jamesy Boy” jumps back and forth between James’ increasing presence and responsibility in Roc’s crew and his tutelage under the man who would become his role model behind bars: convicted murderer Conrad. Rhames’ character is so thinly drawn and is such a stock figure as the wise, quiet elder, he barely registers. And he’s perilously close to functioning as another stock figure: the Magical Black Man. James Woods doesn’t get much to do, either, as the stern, smart-ass warden.

Conrad dreams of fleeing the walls that hold him and traveling to Rio de Janeiro—that’s how he gets through each day. (Presumably, Zihuatenejo was booked.) James, meanwhile, finds his inner voice and strength by writing poetry. He scribbles a little bit in his pad, then looks off reflectively into the distance, then scribbles some more as inspiring music swells. But the poems—and the film as a whole—fail to flesh James out as a whole and complicated human being worth rooting for.