Frankie Wilde is the king of the club scene in Ibiza, a Mediterranean island where jumbo jets ferry in party animals on package tours. He stands like a colossus above the dance floor, vibrating in sympathy with his audience. Lately he’s even started to produce a few records. He has a big house, a beautiful wife, and a manager who worships him. What could go wrong?

Frankie goes deaf. Maybe it was the decibel level in his earphones, night after night. Maybe it’s a side-effect from his non-prescription drugs; given enough cocaine, he makes Al Pacino’s Scarface look laid back. Frankie (Paul Kaye) tries to fake it, but his sets become exercises in incompatible noise.

He and his manager Max (Mike Wilmot) share a painful truth: “Generally, the field of music, other than the obvious example, has been dominated by people who can hear.” (When I hear a line like that, I am divided between admiration for the writing, and concern for audience members who will be asking each other who the obvious example is.) Frankie goes berserk one night and is carried out of his club and out of his world.

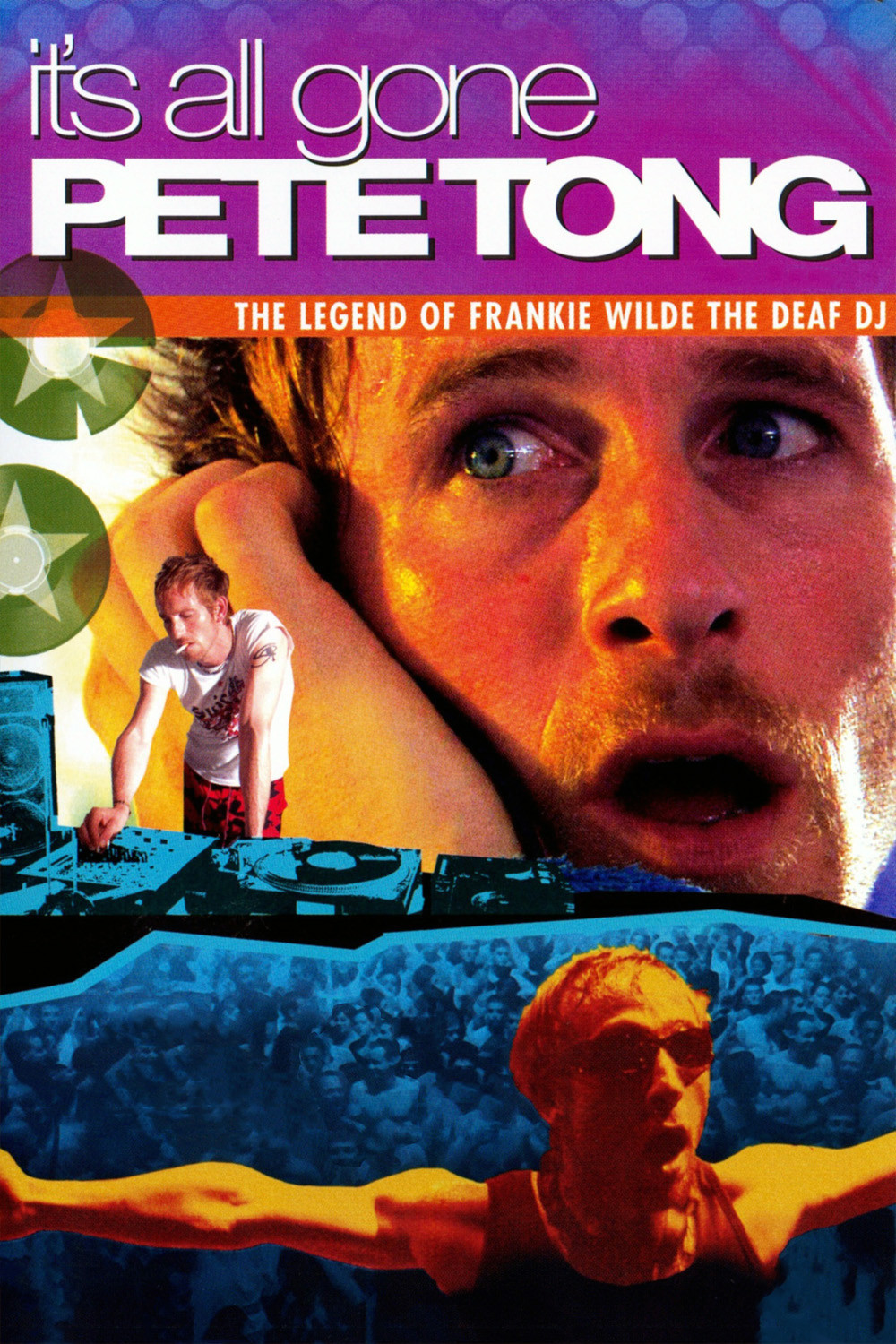

“It’s All Gone Pete Tong” presents Frankie’s story in mockumentary form. Like Werner Herzog and Zak Penn’s recent “Incident at Loch Ness,” it goes to some effort to blur the line between fact and fiction. It insists Frankie Wilde was an actual disk jockey and interviews “real” witnesses to his rise and fall; there are fake Web sites discussing his legend, but the movie is fiction. There really is a Pete Tong, however; he’s a British disc jockey who is seen interviewing Frankie in a doc-within-the-mock.

The title is real, too. “It’s All Gone Pete Tong” is Cockney rhyming slang for “It’s all gone wrong,” and that’s what it’s gone, all right, for Frankie Wilde. His wife and her son bail out, his manager despairs, and Frankie descends into a slough of despond, drink and cocaine. Occasionally he is attacked by a large hallucinatory stuffed bear, reminding me of the bats that attacked Hunter S. Thompson on the road to Vegas. There is a time when he has sticks of dynamite strapped like a crown to his head, but the movie was a little manic just at that moment and I am not completely sure if the dynamite was real, or a fantasy. Real, I think.

The downward arc of the first two acts of the movie is made harrowing and yet perversely amusing by the performance of Paul Kaye, a British comedian who sees Frankie as a clown who overacts even in despair. Then comes salvation in the form of a speech therapist named Penelope (Beatriz Batarda), who begins by teaching Frankie to lip-read and ends by saving his life and restoring him to happiness. Much of the solution involves Frankie’s discovery that he can feel the vibes of the music through the soles of his feet; the discovery comes because, as he claims at one point, he is “the Imelda Marcos of flip-flops.”

The movie works because of its heedless comic intensity; Kaye and his writer-director, Michael Dowse, chronicle the rise and fall of Frankie Wilde as other directors have dealt with emperors and kings. Frankie may not be living the most significant life of our times, but tell that to Frankie. There is a kind of desperation in any club scene (as “24-Hour Party People” memorably demonstrated); it can be exhausting, having a good time, and the relentless pursuit of happiness becomes an effort to recapture remembered bliss from the past.

Note: For me, a bonus was the island of Ibiza itself. It became famous in America in the early 1970s as the home of an author named Clifford Irving, who forged the memoirs of Howard Hughes and almost got away with it. In his defense let it be said that Irving probably did a better job on the book than Hughes would have, and that he gave to the world his mistress, Nina Van Pallandt, who starred in Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye” (1973) as a woman one would gladly forge for, and with.