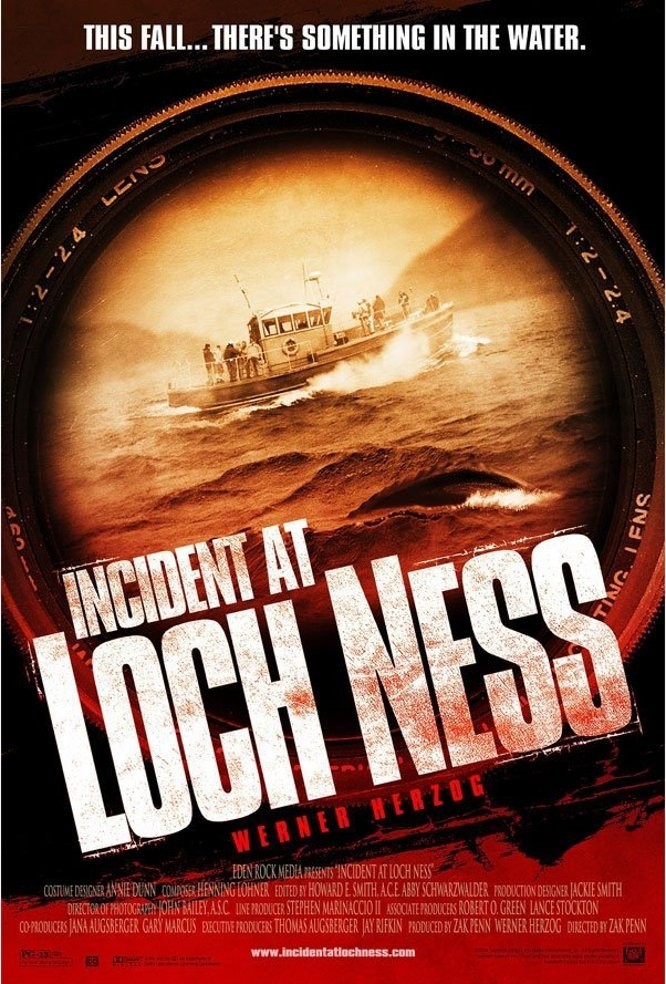

The story goes like this: Werner Herzog, the holy genius of the German New Wave, decides to make a documentary about the Loch Ness monster.

At the same time, a documentary is being made about Herzog by John Bailey, the famous cinematographer. Bailey and his crew follow Herzog and his crew to Loch Ness, where Herzog’s producer turns out to be a jerk who hires his girlfriend as the “sonar expert” and expects everyone to wear official matching jumpsuits “so it will look like a real expedition.” On the suits, he spells it expediition.

Herzog realizes he is in the hands of a charlatan. The “sonar expert” (Kitana Baker) explains that her professional experience includes modeling for Playboy and appearing in the Miller Lite cat-fight commercials. The producer (Zak Penn) also springs a “cryptozoologist” on Herzog, and we learn that cryptozoology is “the study of undiscovered animals.” The crypto guy produces a test tube containing a “mysterious” tentacle of which it can be said that it is definitely small. The sonar expert appears in an American flag bikini. Herzog is enraged that the producer has hired these people; the director should make such decisions.

They are all, meanwhile, on a boat named the Discovery IV; the producer liked the sound of that, despite the fact that there was no Discovery I, II or III. The captain, a grizzled old sea dog (or loch dog) named David A. Davidson, mutters darkly about it being bad luck to change the name of a boat. A miniature fake Loch Ness monster is produced, and Herzog, asked to photograph it, says it is “stupid” and tells Bailey’s doc camera: “I became aware that there was something seriously wrong.” But then something attacks the boat, a crew member is eaten, the producer makes off in the only lifeboat, the sonar expert reveals “I did study up a little” and tries to summon help on the radio, and Herzog dons a wet suit and announces plans to swim to shore for help.

This material falls somewhere between “This Is Spinal Tap” and “Burden of Dreams,” Les Blank’s (real) documentary about the filming of Herzog’s “Fitzcarraldo,” a movie shot deep in the Amazon jungles. There is even a moment when the producer pulls a gun on Herzog, echoing the story (inaccurate, Herzog says) that Herzog forced Klaus Kinski to act at gunpoint.

Is the film what it claims to be, or is it just a contrivance from beginning to end? It must be said that Herzog himself is always completely convincing, and everything he says and does seems authentic. But was he really going to make a documentary? Or is that merely the pretext for this film? Or is this film what emerged from the collision of Herzog’s failed film and Bailey’s documentary? Is there a point at which reality becomes fiction, and everybody redefines what they are really doing?

It’s intriguing to puzzle out such questions, while looking like a hawk for shots that betray themselves. There’s one where two characters go upstairs to have a secret conference, and Bailey’s camera sneaks up after them, and peeks through an open bedroom door and sees a crucial chart reflected in a mirror, and you know this shot didn’t just happen; it was a set-up.

On the other hand, an opening scene at Herzog’s home in Los Angeles seems manifestly real, as Herzog and his wife Lena Grohmann throw a dinner party for the crew of the film and some friends, including Jeff Goldblum and the magician Ricky Jay. It’s at this party that the producer wants to discuss the “lighting package” that the cinematographer, Gabriel Beristain, will be using, and Herzog declares that a documentary needs no lights. Beristain is a real figure, who photographed “K2” and “S.W.A.T.,” and indeed everyone we see is who they say they are (in one way or another), Penn, for example, is the writer of “Last Action Hero.”

Rather than say exactly what I think about the veracity of “Incident at Loch Ness,” let me tell you a story. A few years ago at the Telluride Film Festival, Herzog invited me to his hotel room to see videos of two of his new documentaries. One was about the Jesus figures of Russia, men who dress, act and speak like Jesus and walk through the land being supported by their disciples. The other was about a town whose citizens believe that a city of angels exists on the bottom of a deep lake and can be seen through the ice at the beginning of winter. Wait too long, and the ice is too thick to see through. Crawl onto the ice too soon, and you fall in.

Herzog has made many great documentaries in his career, and I was enthralled by both of these. He’s a master of the cinema, with an instinct for the bizarre and unexpected. After I saw the films, he said he only had one more thing to tell me: Both of the documentaries were complete fiction.

To what degree “Incident at Loch Ness” is truthful is something you will have to decide. Indeed, that’s part of the fun, since some scenes are either clearly real, or exactly the same as if they were. Watching the movie is an entertaining exercise in forensic viewing, and the insidious thing is, even if it is a con, who is the conner and who is the connee?

Author’s note: The Web site www.truthaboutlochness.com supplies a lot of information, speculation and gossip about the film, not all of it necessarily trustworthy.