“Islands in the Stream” is a big, strong, old-fashioned movie about that threatened species, the Hemingway Hero. It celebrates physical courage and boozing all night and the initiation of boys into manhood, and it has a fishing scene, a battle scene, a love scene and a whore with a heart of gold. Papa would have loved it, and no wonder: He wrote it, and in many ways it’s about him.

This was the posthumous Hemingway novel, assembled by his widow, Mary, from various drafts and stages of the work in progress. Its reviews weren’t particularly good, and there’s a possibility that Hemingway, had he lived, might have decided not to publish it. But it makes good movie material: The best movies somehow seem to come from second-rate books, while great literature resists translation into other forms.

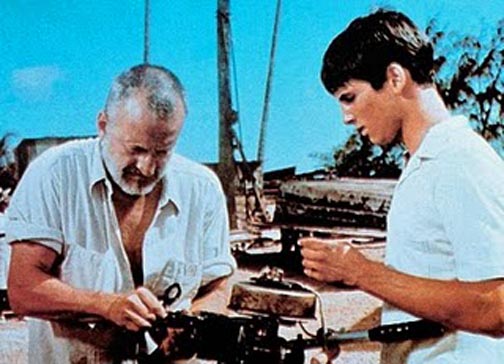

The story takes place in the late 1930s, with the war clouds of Europe showing over the horizon. George. C. Scott, as Thomas Hutson, bearded sculptor, twice-divorced, rugged individualist, patrols the beachfront of his Caribbean home. He has a beer gut but projects a lot of latent strength, and he’s clearly at home here. He inspects his boat, diagnoses his first mate’s nearly terminal hangover, and repairs to the local hotel for a drink and some repartee with his favorite hooker. It’s a big day: His three sons are coming for a visit.

We’ve already guessed that, because the first third of the film is boldly labeled “The Boys” (later we get “The Woman” and then “The Voyage” – nothing like your Hemingway story divisions written bold against the sunrise). The oldest boy, almost old enough to go off to war, is by his first wife and only true love; they were divorced because they hurt each other too much. The other two sons are by a second, less remarkable, former marriage.

The older boy is a good one, and Hutson loves him. The middle son is the problem: He remembers Hutson’s mistreatment of his mother, and hates and fears him. But his hatred is exorcised during a scene which is, at one level, pure Hemingway B.S., and at another level, remarkably exciting. The boy hooks a giant sport fish, and does battle with it for hour after hour in the blinding sun. His hands are bleeding, and his feet where they cut into the railing, but he won’t let anyone else handle the fish. And his struggle becomes an initiation into manhood: Somehow (the reasoning is a little murky), by proving himself a man he can confront his father as equal and so no longer needs to hate him.

The boys fly back to the states, where the oldest enlists in the Canadian Air Force, and Hutson’s life settles back into a routine of male camaraderie, drinking, sculpting, and frequenting the hotel. Then one day, unexpectedly, his first wife (Claire Bloom) arrives. They talk and remember and drink, and then, in one of those stunningly beautiful moments that can redeem any film, Hutson realizes why she has come. She has come to tell him that their son is dead.

Scott plays this scene with immense intelligence: The conversation meanders without building, and the hot day drones on, and his former wife asks for another drink just a little too urgently. His back is turned to us when the realization hits him. He reaches up and touches the back of his neck as if a ghost had breathed there, and somehow the way he stands there, the angle of his hand and head, tell us what he’s realized.

The film’s third movement is the least satisfactory: Jewish refugees arrive on the island, and Hutson, perhaps out of unresolved guilt about his son, engages to smuggle them into Cuba on his fishing boat. There are beautifully photographed scenes along an inland river, and some fighting and dying, but the film seems to have lost its touch right at the end. Overlit flashbacks and fantasies are supposed to represent a man’s dying thoughts but represent, instead, a last gasp of cinematic imagination.

The supporting performances are good (David Hemmings looks physically transformed as he sinks into the role of the alcoholic boat’s mate). The physical appearance of the film is stunning (the director, Franklin J. Schaffner, and the cinematographer, Fred Koenekamp, worked together with Scott on “Patton”). There are a few rough spots, especially with the ending and with some particularly phony special effects purporting to show burning ships. No matter; for most of the way, “Islands in the Stream” plays it well and good and honestly, as someone might once have said.