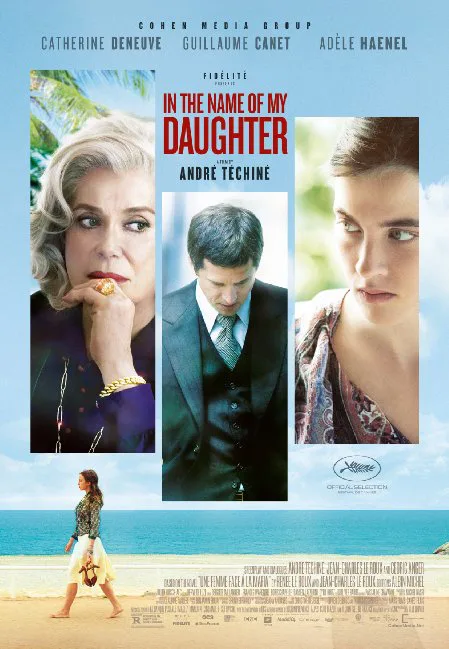

“In the Name of My Daughter” is the seventh André Téchiné film to star French legend Catherine Deneuve. Deneuve shares top billing, but she’s really a supporting character in this drama based on the book written by the real-life casino boss she plays, Renée Le Roux. Le Roux was the mother of Agnes Le Roux (Adèle Haenel), a twentysomething divorcee and heiress who may have been murdered by Maurice Agnelet (Guillaume Canet). The film barely seems to care about Agnes’s disappearance and the ensuing criminal trials, squeezing them into the shortest of its three acts. Those looking for a courtroom drama or the emotional tugging that might result from a mother’s 30-year fight to get justice for her daughter will find little to chew on here.

Instead, we’re primarily privy to a power struggle between Renée and Fratoni (Jean Corso), a fellow casino boss with Mafia ties who wants to take over her casino, and Agnes’s doomed love story. Both of these plotlines have Agnelet in a prominent role. While serving as Renée’s lawyer, he advises her to serve as the new president of her casino in the hopes of riding her coattails to a high position within the organization. When that fails, he goads the smitten Agnes into colluding with her mother’s enemy to wrest away control of the casino.

Renée and Agnes have a frayed relationship, made even more troubled by Renée’s refusal to give Agnes her inheritance money. Agnes is at first depicted as independent, opening her own bookstore and taking the initiative in how she paces her relationship with Agnelet. As the film progresses, however, she becomes stereotypically dependent and unhinged, stalking a man who clearly does not love her and writing pages upon pages of florid diary entries. Haenel gives her performance more shadings than one might expect—her sense of guilt as she betrays her mother is superbly underplayed—but her multiple scenes of obsession become redundant.

Agnelet is the kind of creep women in movies fall for all the time. He’s upfront about his commitment phobia, blatantly juggling multiple women at once, yet everyone he screws goes mad for him, hoping he’ll surrender to their eventual pleas for monogamy. One of his current friends-with-benefits, Françoise (Judith Chemla), warns Agnes about Agnelet’s player tendencies before Agnes gets involved. Later, during her court testimony, Françoise evokes that dreadful scene in Minnelli’s “Gigi” where the old French women reminisce about their first suicide attempts over a man. “Every woman has tried to kill herself over Maurice,” she says nonchalantly. “Even me.” Honey, he is not all that.

Despite the real-life outcome of the four trials (the last of which is being appealed) Téchiné has said he didn’t want to make a film passing judgment on Agnelet. However, Canet doesn’t play him as anything but varying shades of guilty. That’s actually refreshing, as it forces you to focus on everything else, from his actions to the people with whom he interacts. He convinces Agnes to open two joint bank accounts to deposit Fratoni’s bribe money, then when Agnes disappears, he transfers all the money to his account solely and runs off to Panama. He remains there for 30 years until he voluntarily returns to face charges brought against him by a distraught and determined Renée.

Deneuve is in command of the first act of “In the Name of My Daughter,” where she deals with the problems faced by her crumbling casino empire. Renée is powerful and committed, driven in ways Deneuve hasn’t been in her other Téchiné roles. She disappears for much of the love story, but her courtroom speech at the film’s end is so good it almost makes up for the rushed, haphazard way the film handles its third act. Agnes disappears 20 minutes before the closing credits, and the ensuing courtroom scenes feel tacked on to the point where you wish the movie had just ended with her disappearance and some title cards describing what happened next.

While not entirely successful, “In the Name of My Daughter” does have some standalone sequences that are quite good. An impromptu sing-along in the car between Renée and her devoted Italian chauffeur Mario (Mauro Conte) is framed to capture both the gorgeous scenery and Deneuve’s joy in singing “Stand By Me” in French. Agnes’s nude inspection in the mirror before sleeping with Agnelet is an all-too-rare moment showing a female character’s satisfaction with her own body image. And the aged Agnelet’s giddy barroom response after one of his acquittals has a chilling amorality.

Since Agnes’s body was never found, we may never know what happened to her. “In The Name of My Daughter” refuses to speculate, which is fine, but I still wish it had given me a bigger peek into the struggle that gives the film its title. Instead, we’re left with Mafiosi and l’amour fou, neither of which is as compelling as a mother’s love.