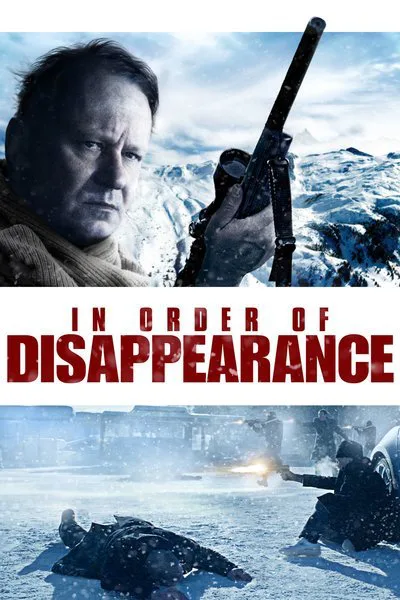

The body count that Stellan Skarsgård’s taciturn snowplow-operating Nils Dickman racks up in Hans Petter Moland’s revenge-thriller-comedy “In Order of Disappearance” almost makes Dirty Harry look like a softie. Liam Neeson wreaking havoc around the world after his daughter is kidnapped yet again in the “Taken” franchise seems like a slacker in comparison. Nils is a gloomy civil servant just voted “Citizen of the Year” for his tireless devotion to keeping the roads clear. When his son turns up dead from an apparent drug overdose, he knows it was murder, and, in trying to track down who did the deed, unveils a web of international drug-runners operating out of the tiny nearby airport in the isolated snowy middle of nowhere. Nils sets out to kill whoever was responsible. He is as unstoppable as his snowplow.

As Nils discovers the scope of this thing, he works his way to the top, because whoever is at the top is the one who really needs to pay. Each person who dies gets their own little epitaph screen, operating like a cynical little chuckle as Nils checks the name off the list. Maybe the cynical chuckle is Moland’s. It’s a fun device the first three or four times it occurs, but the joke becomes increasingly rote as it goes on.

The fun of the film (and it is often fun) is in the complexities of interconnections, and the sheer number of criminals raging through this tiny area, outnumbering the upstanding citizens by the looks of it. All of the secondary characters, the bumbling cops, the warring drug dealers, their families, their rivals, are all broad caricatures played by a very funny cast of character actors. Somebody is killing them all off one by one and everyone points the finger at everyone else, never once suspecting that that hunched-over guy at the wheel of the snowplow is the murderous maniac responsible. The head honcho in the area is Greven (Pål Sverre Hagen). Greven is a flamboyant villain, a childish psychopath who also happens to be a ponytail-wearing militant vegan. He is sure that it’s the Serbians doing the killings (he keeps referring to them as Albanians, and is enraged when corrected). Greven has his goons go after the Serbians, the Serbians retaliate, the epitaph credit-screens pile up. Some of the “bits” in the film are full-on farcical, and some have a wintry dry wit. Others feel improvisational, like Greven spluttering at his wife: “You think you know me! But you don’t fool me, with your fucking hipster mittens!”

Cinematographer Philip Øgaard captures the white-out conditions of “In Order of Disappearance” in ways haunting and eerie. He has a good eye for the weird and specific: the gravestones jutting up out of the endless expanse of white, the blue-white snow at night with Nils’ snowplow light cutting its way through the darkness, plumes of snow billowing off to the side. “Fargo” might come to mind, but this snowy wilderness is different, harsher. Nils wraps the dead bodies in chicken wire and dumps them over a roaring waterfall plunging into an icy river below.

This is Skarsgård’s third collaboration with Moland (“Aberdeen,” and “A Somewhat Gentle Man” being the other two), and he’s really not given much to do. He’s a blank-faced killing machine. Nils remains a completely undeveloped character, although character development is clearly not what Moland was after. Moland was after the humor concept of a bunch of drug lords fighting over who gets to deliver cocaine to a tiny patch of snow. It’s as if Quentin Tarantino went to the Arctic Circle. The character of Nils certainly can’t compete with the eccentric secondary characters, the Serbian goombahs snarling with rage over the battle of Kosovo (which went down in 1389) and Greven downing a vegan smoothie as he screams at his second-in-command. The killings are creative and brutal, but eventually, the whole structure of it, with the epitaphs announcing the deaths “in order of disappearance”—becomes an empty and slick exercise in style.