Accordion music makes me feel happy. Heaven, if I am given a choice, will include an Italian restaurant with an outdoor patio, shaded by a grape arbor, under which large plates of spaghetti are served while an accordion plays in the twilight (“Arrivederci Roma,” please).

There is a lot of accordion music in “Arizona Dream” – too much for most people, I suppose, especially since the song is usually “Besame Mucho,” played over and over, sometimes to turtles. But I am forgiving, especially since the accordion player is the irreplaceable Lili Taylor, with a cigarette stuck in her mug.

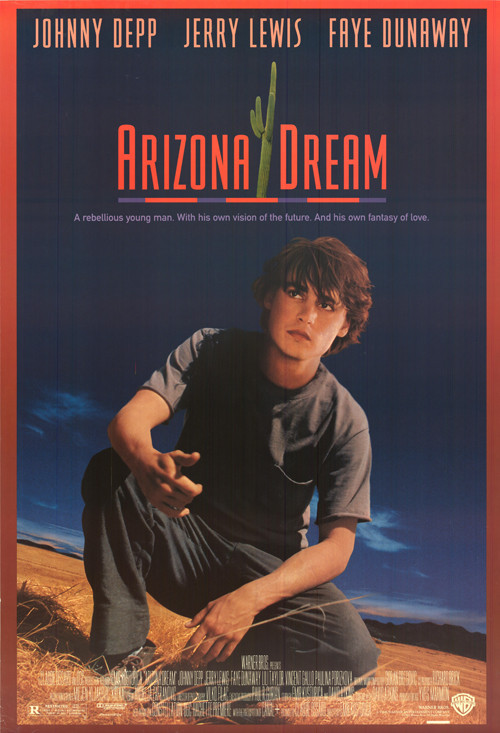

Here is a movie containing wonderful sights. Ambulances to the moon. Unsuccessful suicide by bungee cord. Johnny Depp. A dog saving a man from death in the Arctic. Faye Dunaway. Turtles crawling through meatballs. Jerry Lewis. A man who counts fish. Paulina Porizkova. Airplanes that look like they were borrowed from “Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines.” Michael J. Pollard.

Thunderstorms.

“Arizona Dream” is one of those movies that slips through the cracks. Hollywood bureaucracy has been established precisely to prevent films like this from being made. And yet it was made, and it is goofier than hell – you can’t stop watching because nobody in the audience, and possibly nobody on the screen, has any idea what’s going to happen next.

The movie was directed by Emir Kusturica, a Yugoslavian (if such a place still exists), whose “Time of the Gypsies” (1989) won the best director award at Cannes. In his world, strange magic happens. People want to fly, and sometimes they can. Eccentricity is prized. That earlier film followed a gypsy family as it traveled through Yugoslavia and Italy, taking its occult knowledge with it.

Now Kusturica has come to Arizona, which he sees as a similar land of enchantment.

The story involves Johnny Depp as a fish-counter who works in New York harbor: “Most people think I count fish, but I don’t. I listen to their dreams.” He is summoned west by an uncle (Jerry Lewis), who runs a Cadillac dealership near Tucson and wants his nephew to continue the family business. Depp arrives reluctantly, uninterested in cars, fascinated by the dreams of fish, to find his uncle preparing to wed a young girl (Candyce Mason). “He’s trying to teach me to stop crying,” she helpfully explains to Depp, during a fitting for a wedding gown.

Depp has never much liked his uncle (“He reminded me of the smell of car dealers’ cheap cologne; he always looked like a 10-year-old boy whose sleeves were too long”). But he decides to stay for a time, and one day an exotic sight appears at the car lot: Faye Dunaway, widow of a rich miner, with her stepdaughter, played by Lili Taylor. Depp and Dunaway immediately feel a deep gravitational pull, and Depp finds himself out at their ranch, engaged in torrid lust, while Taylor wanders in the yard, playing the accordion.

What happens next, involving airplanes and ambulances, turtles and yo-yo suicides, I dare not say. There is a talent show at which someone does a credible imitation of Cary Grant during the crop-dusting scene in “North by Northwest.” And strange scenes on rooftops and treetops in thunderstorms.

Needless to say, Warner Bros., having somehow made this film, is not going to encourage such a lapse by releasing it, and so it can only be seen on the specialized circuit. The version opening tonight at the Film Center of the Art Institute of Chicago is the director’s cut – some 20 minutes longer, I am told, than the version I saw in September at the Telluride Film Festival. I could not tell you which 20 minutes have been added, but at 142 minutes one does not long for it to be longer.

What we are dealing with here is a filmmaker who has his own peculiar vision of the world, and it does not correspond to the weary write-by-numbers formulas of standard screenplays. If he has a guide, it might be his fellow Yugoslavian Dusan Makavejev, whose own films show a similar cheerful mix of odd people and strange inventions. The movie is completely batty, and better suited probably to a giggly 1960s audience than to today’s grim seekers after cinematic value for money.