Saints are a great inconvenience. They interfere with the plans of ordinary people. When a modern family finds itself with a saint in its midst, there is a tendency to send for the psychiatrist.

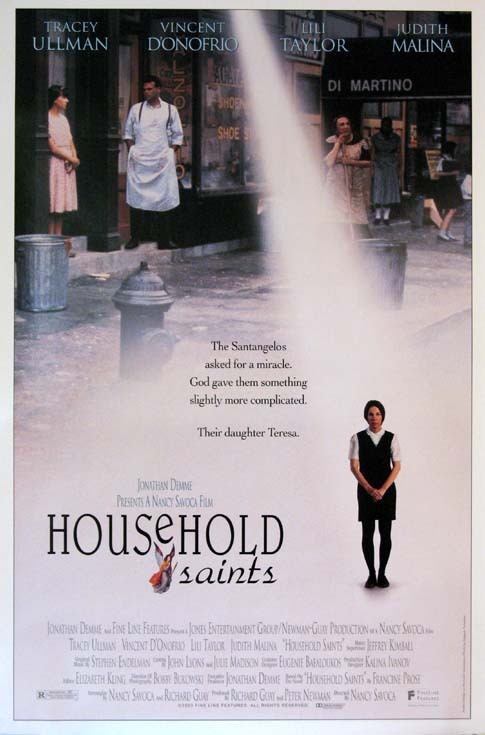

“Household Saints” is about Italian Americans in New York City who begin with a form of madness they are comfortable with, and end with a madness only a saint could understand.

Like many stories of miracles, this one begins with a pinochle game. The local butcher, Joseph Santangelo, has fallen in love with Catherine, the daughter of his card-playing buddy, Lino Falconetti (Victor Argo). The stakes in their game go higher and higher one night, until finally Joseph wants to play for the right to marry Catherine. Lino agrees, and loses, and goes home and orders his daughter to fix a nice dinner because the Santangelos are coming over.

“I want you to make a meal so good a man would get married to eat like that every night,” he says. “I got news for you,” she says. “Nobody gets married for the food.” And particularly not her cooking, which is so haphazard that Joseph’s mother insults the cooking right there at the table.

But Joseph (Vincent D'Onofrio) and Catherine (Tracey Ullman) do get married. And gradually they change. As young people they look like the “before” pictures in an ad for a beauty school. Catherine is particularly careless, with her lank hair and her tendency to spend the day locked up with a book. But eventually prosperity touches them. Joseph grows a mustache and goes to a better barber.

Catherine tints her hair and uses makeup.

It is a constant trial, living with Joseph’s shrill and hateful mother (Judith Malina), who spends Catherine’s first pregnancy pumping her full of horrifying old wive’s tales – superstitions about all the things that can lead to miscarriages or the birth of monsters. When Mrs. Santangelo finally dies, Catherine paints the dark old apartment in bright pastels and buys Tupperware, and the family enters the 20th century.

To them a daughter is born. Teresa (Lili Taylor) is a quiet, serious girl who grows up as a devout Catholic. She is attracted to that uncompromising thread of Catholicism that challenges her to become a saint. She prays, meditates and spends her days in penance and good works. She develops a special devotion to the her namesake, St. Teresa, known as the Little Flower of Jesus. She agrees with the saint that it is not necessary to do great things in the world to be holy; one can do God’s work anywhere, and there is grace to be won by scrubbing floors.

Teresa is a child who would be completely understood by her superstitious grandmother. Her parents have become modernized, however, and while of course they are Catholics, they don’t see any need to get carried away with things. When Teresa shyly announces her hope to enter the convent, her father explodes: “I don’t want no daughter of mine lining the pope’s pockets.” By now it is about 1970. Change is in the air. Teresa enrolls in college, where most students are on the floor in sit-ins, not prayer. She meets a young man named Leonard Villanova (Michael Imperioli), who explains that he has a Life Plan: “First, I get the St. John’s law degree. Then I want a Lincoln Continental. I want a family and a town house on the upper East Side, and I want membership in all those clubs that always turned up their noses to the Italians.” He plans a career in “television law.” Teresa is impressed: “You mean like Perry Mason?” “Household Saints” is a wonderful movie, without a second that isn’t blessed by the grace of its special humor and tenderness. But the closing scenes are transcendent, as Teresa drifts away from the Villanova Plan and into a plan of her own, for loving Jesus. The fact is that modern people do worship false gods and that a life devoted to getting a big car and a town house is seen as eminently more sane than a life devoted to God. You can decide for yourself whether Teresa goes mad. In an earlier age, people would have known how to think of her.

This warm-hearted jewel of a movie was directed by Nancy Savoca, whose previous films are “True Love” and “Dogfight” (which also starred the priceless Lili Taylor). She treasures eccentricity in people. Another director might have started right off with the story of Teresa. But Savoca’s subject is larger: She wants to show how, in only three generations, an Italian family that is comfortable with the mystical turns into an American family that is threatened by it. And she wants to explore the possibilities of sainthood in these secular days. That she sees great humor in her subject is perfect; it is always easier to find the truth through laughter.

Some people will question Teresa’s devotion to the Little Flower. For me, the movie rang one bell of memory after another. I went to Catholic school in the 1950s – that age of Latin, incense and mystery before Vatican II repainted the Church in politically correct pastels. I know this movie is closer to the literal truth of those days than many non-Catholics will believe. When was it, I wonder, that it became madness to want to be a saint?