If you wanted to make a movie about the life of Steven Russell, you might start with this question: Could we get Jim Carrey? You would need an actor who can seem both instantly lovable and always up to no good. That “I Love You, Phillip Morris” is based on a true story is relevant only because it is too preposterous to be fiction. Russell is a con man, and his lifelong con is selling himself to himself.

That process begins when he discovers he isn’t who he thought he was. His parents tell him he is adopted. My notion is that if you love your parents, and they tell you you’re adopted, you’d love them even more. It doesn’t work that way for Steven Russell. Once that rug has been pulled from beneath his feet, he sets about creating a new reality for himself. He becomes a police officer. He marries Debbie (Leslie Mann), as wholesome as a toothpaste model. They have two children. He plays the church organ. He is a poster boy for truth, justice and the American way.

Continuing to seek truth, he discovers the identity of his birth mother. Shall we say she is a disappointment. After a traumatic accident, he has time in the hospital to reflect that his entire life has been constructed out of other people’s spare parts. Who is he really? He decides he is gay. Not only gay but flamboyantly, stereotypically gay, and soon living with a Latin lover (Rodrigo Santoro) on Miami’s South Beach. He begins to pass checks and fraudulently use credit cards to finance their heady lifestyle.

Now when I wrote “he decides he is gay,” did some of you think you don’t “decide” to be gay — you simply are, or are not? I believe that’s the case almost all the time. I’m not completely sure about Steven Russell. The movie reveals him as an invention, an improvisation, constantly in rehearsal to mislead the world because he has a need to deceive. Who could be less like a church-going cop and family man than a South Beach playboy? Does he like gay sex? Yes, and very energetically, indeed. Does he like straight sex? You bet he does. He can sell himself on anything. I think gay sex is the easier sell here.

The method of “I Love You, Phillip Morris” provides great quantities of plot and then holds them at arm’s length. It isn’t really about plot. Plots are scenarios that characters are involved in. Steven Russell improvises his own scenario, so that most of what happens is his own handiwork in one way or another. Carrey makes the role seem effortless; he deceives as spontaneously as others breathe.

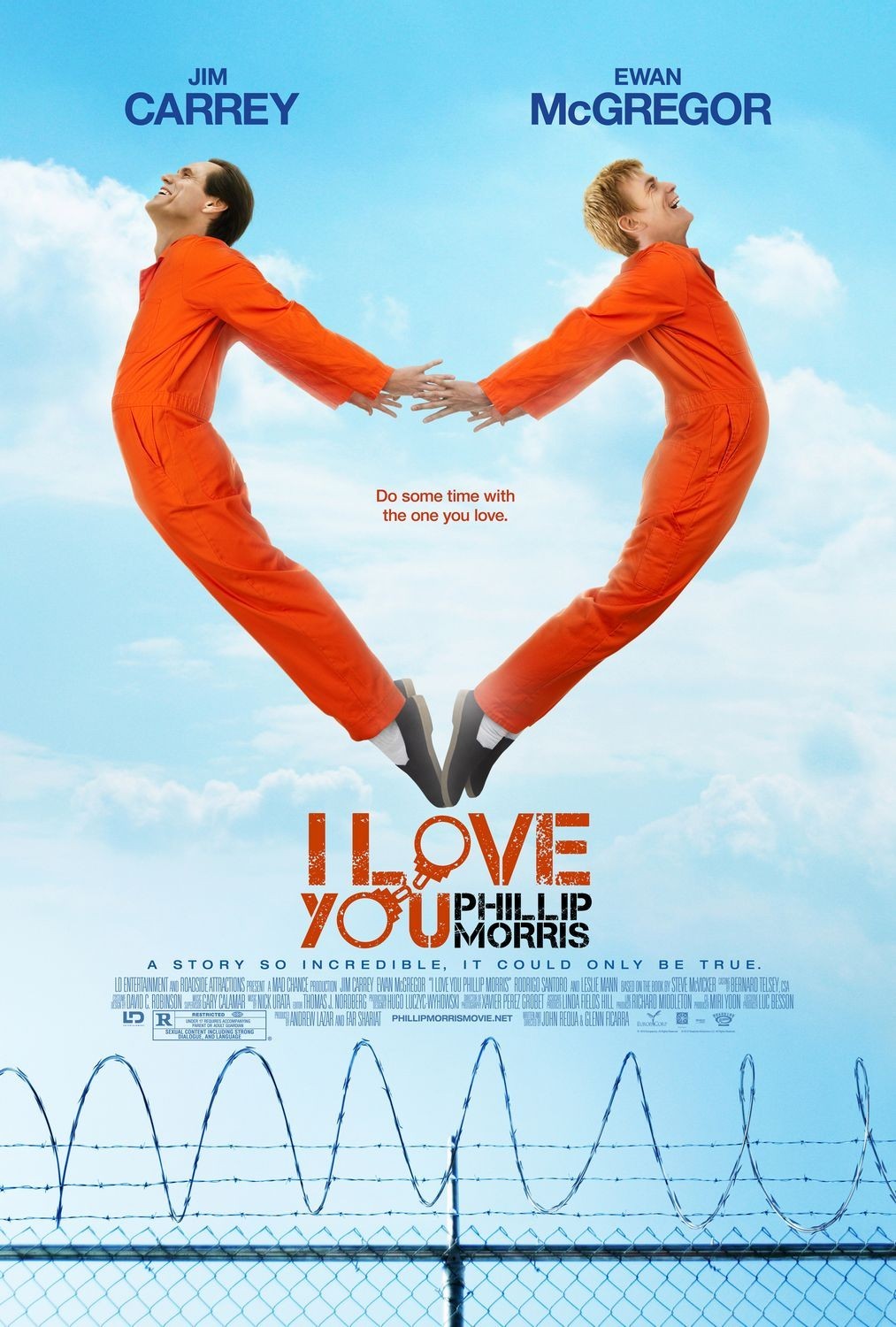

The authorities have a supporting role. He keeps breaking the law, and they keep arresting him. After he’s imprisoned for theft and fraud, life changes when he’s assigned a new cellmate: Phillip Morris (a blond Ewan McGregor as we’ve never seen him before). He falls in love. Or perhaps, as the song has it, he falls in love with love. After he’s released, he creates a new persona, a lawyer, and floats this deception with a single shred of proof to pull off a stunt that gets Phillip out of prison. McGregor rises to this occasion like a dazzled ingenue.

Phillip is in love with Steven; that’s not in doubt. But he is slow to understand the depth and complexity of Steven’s fabrications. He’s a sweet, naive kid with a Southern accent and not the brightest bulb on the tree. He’s a bystander as Steven steals a fortune from a health-care organization that has possibly never even employed him. Steven is soon back behind bars, and the movie unfolds into a series of increasingly audacious and labyrinthine confidence schemes.

All of this, as I said, is based on Russell’s own story, as written by Steve McVicker of the Houston Press. Russell impersonated doctors, lawyers, FBI agents and the CFO of a health-care company. He convinced prison officials he had died of AIDS and later successfully faked a heart attack. He escaped from jail four times (hint: always on a Friday the 13th). He is now serving 144 years in Texas in maximum security and solitary confinement, which seems a bit much for a man who never killed anyone and stole a lot less money than the officers of Enron.