Somewhere in the woods is a lovely old country home, and somewhere in that home is an upper-middle class family that’s about to be tested, and have its hypocrisies called out and its secrets exposed. This could be a description of a lot of movies, but it just so happens that this time it’s of “Human Factors,” writer/director Ronny Trocker’s drama about a complacent bourgeoisie family that begins to unravel after their country home is invaded. Maybe “invaded” is too strong a word: the intruders were hiding somewhere inside the building and fled as soon as they were discovered. But the event is still enough to initiate a chain of disruptions and reckonings.

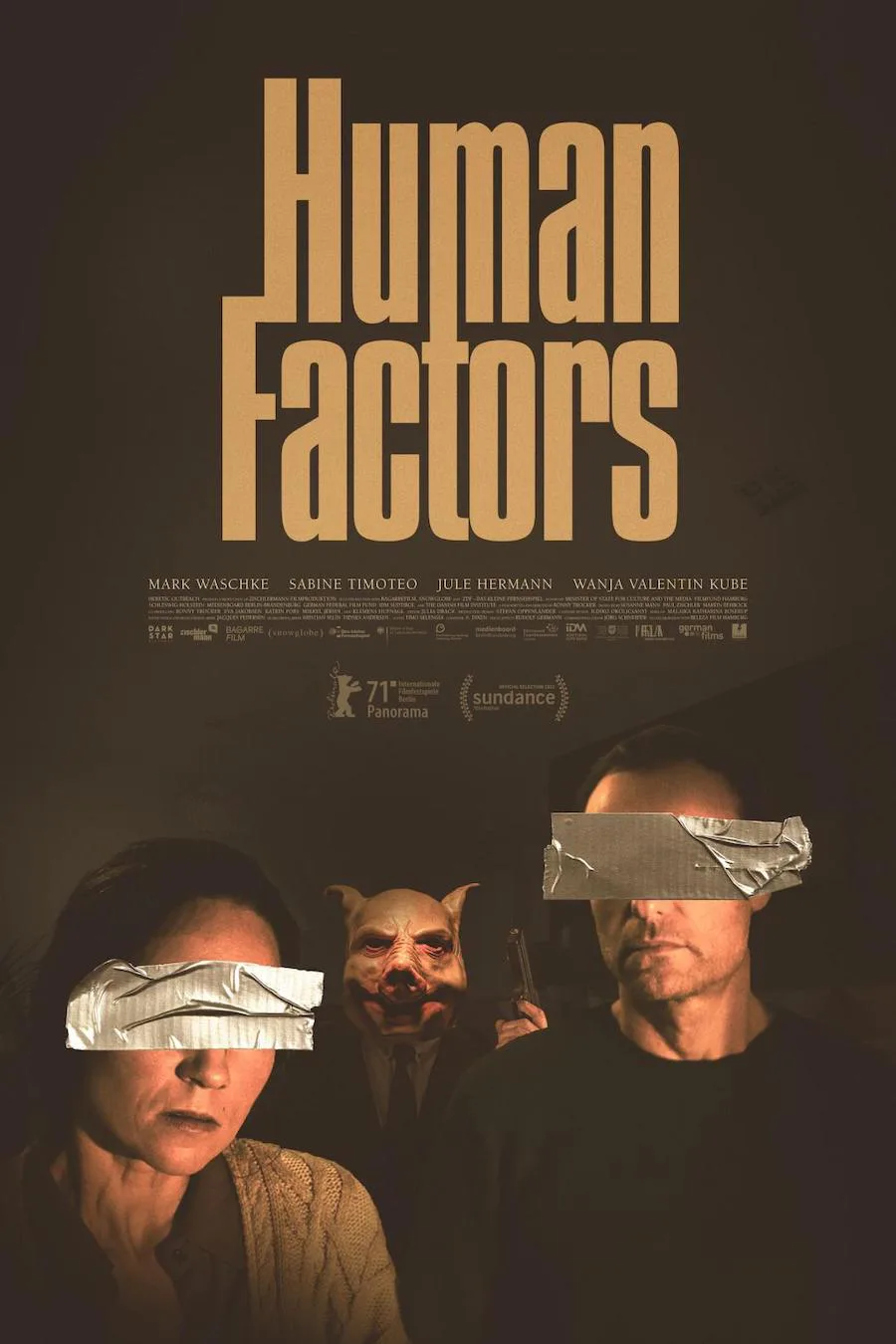

The family consists of a father, a mother, a teenaged daughter, and an elementary school-aged son. The father, Jan (Mark Waschke) and the mother, Nina (Sabine Timoteo), are founding partners at an advertising agency. They have a place in the city and a second home out in the woods, which is where much of the tale is set. Their teenage daughter, Emma (Jule Hermann), is a standard type for this kind of film: a smart, respectable girl who acts out a little bit, partly in protest of her parents’ hypocrisies, but seems too sensible to slide totally off the rails. The son, Max (Wanja Valentin Kube), is a sweet and adorable lad with an unspoiled imagination and loads of empathy (his first concern is his pet rat, who went missing during the intrusion).

Trocker is deft at creating situations that go right up to the edge of blatant symbolism or metaphor, bit resist the urge to pitch themselves over the brink and become blatant and simplistic. Consider the appearance of the intruders. It roughly coincides with Jan revealing to Nina that he landed a major political account without asking her permission or even warning her that it was in the works.

The problem is twofold. One, Jan and made a promise not to take political accounts. Two, the account Jan landed is a right-wing politician whose campaign is rooted in xenophobic and racist messages aimed at bigoted white natives. Jan justifies taking the account on grounds that it will enrich the agency’s bottom line. Then (perhaps intentionally) he misinterprets his wife’s distress, assuring her that the agency’s staff can handle the increased workload. When it becomes clear how shaken Nina is, Jan becomes blandly evasive. Nina’s shock, distress, and confusion at the new account (which her husband sought and accepted without consulting her; so much for his seemingly New Male sensitivity) is all bound up with her reaction to coming home to what she expected would be just another evening and finding masked individuals jumping out of hiding places and running away when confronted. There is speculation that the intruders were part of a protest aimed at people like Jan who are helping right-wing racists, but like almost everything else in the movie, this question is never settled.

The performances and direction in “Human Factors” are sensitive and intelligent. Many scenes are marked by a subdued filmmaking intelligence that has become increasingly rare, such as the way the camera adopts a voyeuristic perspective that’s not tied to any single person, or the way that Trocker times the appearance of trains and automobiles in the backgrounds of tracking shots so that they subtly mirror what’s happening in the family (a sudden event that feels like a shocking, disruptive surprise but that in retrospect arrived so predictably that you might say it was “on schedule”). The home intrusion is replayed from several perspectives that supply new bits of information not included in previous takes, while withholding data in such a way that we understand why that specific character would have had a different reaction than the rest. Some characters come off better in the retellings than others. Jan is the worst by far: there’s even an implication that he heard the break-in while taking a phone call on the perimeter of the property and declined to investigate even after hearing his wife’s cries of distress.

“Human Factors” is a sick-soul-of-the-bourgeoisie drama, a type of film with which English-language art house patrons are familiar. The main characters tend to be solidly upper-middle-class or rich (it can be hard to tell the difference; rich people who inherited their wealth rarely admit they’re rich). There tend to be fabulous, often bespoke cable-knit turtlenecks and pullovers everywhere you look, and beautiful people who should not be smoking bumming cigarettes off each other by the side entrances of posh restaurants, or in back of guest homes or boathouses. Sometimes these characters are single or divorced, but more often they’re part of a traditional “nuclear” family (although the father might be on his second marriage, with a former student or assistant or nanny).

From early classics like Luis Bunuel’s “The Exterminating Angel” and “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” through high-flown poetic exercises like the “Three Colors” trilogy, Michael Haneke’s thrillers “Cache” and “Funny Games,” and the domestic dramas “Human Resources” and “The Humans,” it’s an elastic format, united mainly by its emphasis on a narrow slice of economic reality. It probably goes without saying that the type of character/family/demographic showcased in such films is wildly overrepresented in cinema history, relative to the population of the planet, and all the configurations of human relationships that have yet to have had even one film made about them.

That having been said, “Human Factors” is a strong example of the form, even though it may overestimate some viewers’ desire to see the comparatively minor afflictions of the comfortable examined in detail, from multiple vantage points. The film’s mordant punchline sure does land, though, and it’s hard not to appreciate its candor: something like, “The next generation will rebel, probably for personal rather than ideological reasons, and end up replacing their parents, and the cycle will continue, and nothing will really change.”

We as a society still haven’t gotten the personal jetpacks promised to us by mid-twentieth century science fiction, but perhaps they will arrive eventually, and the well-off families in these movies will be wearing them, arguing about the larger significance of protocol infractions while hovering over Paris or Lisbon in fabulous sweaters.