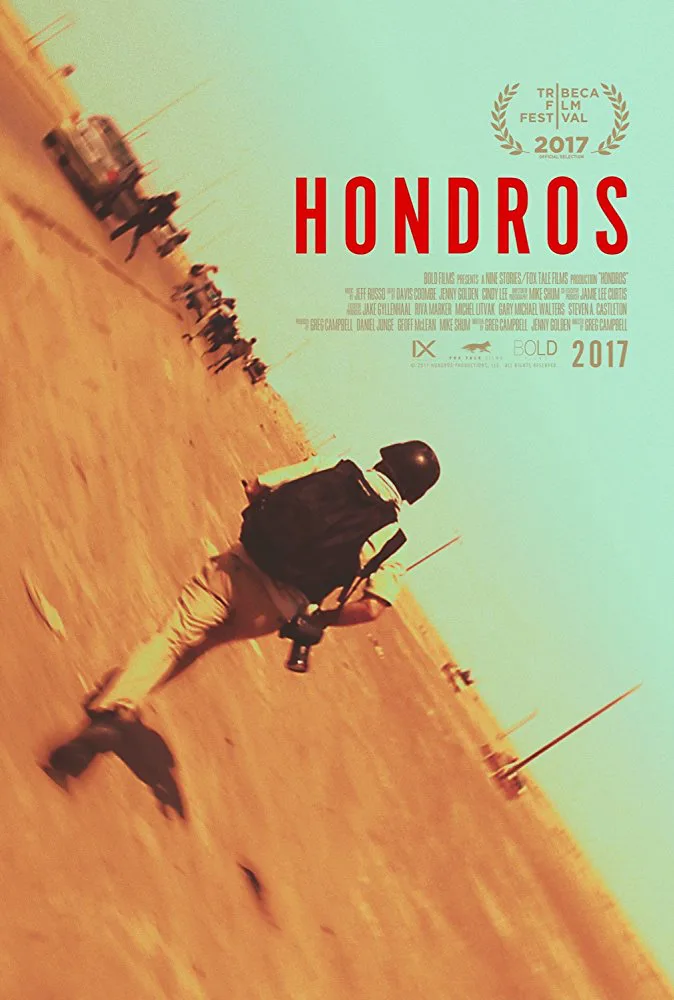

Bullets fill the air, cracking on the ground and fired from the unwise hands of child soldiers; explosions punctuate the anger in the latest battle within the world. In this moment, a young Liberian man on a bridge fires his RPG and hits his target, jumping for joy. The world would not have seen his unforgettable display of elation and aggression were it not for Chris Hondros and war photographers like him, who exhibit a profound dedication to capturing humanity and furthering journalism. This famous image of Hondros’ took on the significance of many others—a story—but is just one chapter that for a rich life, as lovingly and compellingly captured in this documentary by his best friend and fellow journalist, Greg Campbell.

Campbell vividly tells the story of Hondros’ life and of his art, focusing on the different violent conflicts he found himself at the center of (Liberia, Kosovo, Iraq, Lybia, for starters). Having died on the job in 2011, Hondros speaks in select talking-head footage, always with a stunning matter of fact nature about the awful, and wonderful things he has documented for the rest of the world to see. As “Hondros” recounts his life and revisits some of the people involved with them, there’s an exploratory nature: while Hondros was of little mystery to Campbell and to others, the movie seeks to comprehend the incredible empathy that inspired so many of his great photos, and sent him to the heart of so many hellholes on Earth.

Other bits of life are provided about Hondros, making him a most complicated man even if the documentary’s many memories of him taking care of others makes his compassion sound superhuman. But I was particularly touched by Hondros’ love for Bach’s cello suites, a kindred voice for Hondros’ work as a solitary voice, finding its way through beauty and tragedy in the world. There are also intimate but not overbearing images painted about him at home, like being a son (he didn’t tell his parents about the other two times he went to Kosovo), or a loving fiancee, after spending an incomprehensible time alone due to his passion.

Often labeled as a storyteller, Hondros captured a lot complicated definitions of the very broad term “the human experience.” The documentary celebrates that when interacting with people who were the subjects of his work, but also at the receiving end of his off-the-clock, seemingly unending compassion. With Campbell providing conclusions to some of these life stories, he gets excellent moments about the aftermath of war when talking to the man who fired that RPG, or later when addressing a young Iraqi woman who was the subject of one of Hondros’ famous pictures. Her reaction to an American soldier’s regret about the tragic moment in which they intersected is not one of love, and “Hondros” continues the theme of his work by having an unflinching take on complicated humanity.

“Hondros” is the type of movie where the praise on its subject becomes predictable; no one particularly criticizes him, especially as his cocky, secretive and in turn lonely nature inspires more admiration than frustration. But as much as “Hondros” does edge towards simplifying a man as being superhumanly compassionate, Campbell makes a strong case that someone who has experienced so many extraordinary events could indeed be extraordinary themselves.

While “Hondros” prevails with its intimate POV, it also makes for a wide-scope tribute to the very profession of photojournalism. Others chime in with their own experiences, as Campbell creates a rich idea of this working family that respected each other, their collective life experiences easily beyond those of most people on the planet. In turn, it becomes believable that Hondros was one of their very best, exemplifying the many values their profession touches upon. In further support of the photojournalists, Campbell highlights how the job is as significant to art as much as it is information.

The documentary is also a testament to the very act of being there itself. Seeing the photographs that Hondros captures is exhilarating, but that the doc is able to match them with footage of that particular event offers a unique spectacle. That’s in part thanks to Campbell, who filmed some of the heart-pounding footage himself; it neatly ties up the film’s delicate poetry about people who are connected by sharing the worst, and best, life experiences.