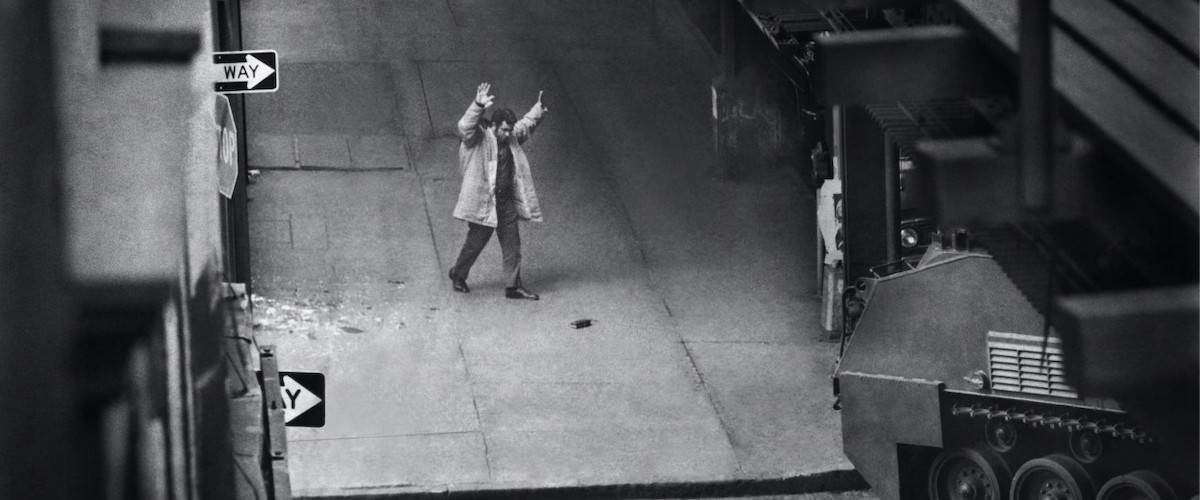

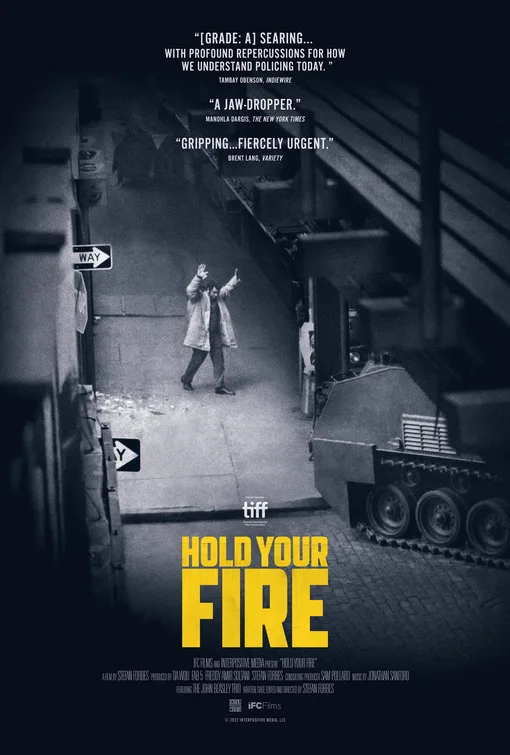

The excellent and infuriating “Hold Your Fire” has all the twists and turns of the best hostage movie thrillers. That it is a documentary supports the adage that truth is often stranger than fiction. Since the 1973 heist this film investigates was covered around the clock by New York City television stations and news outlets, writer/director/editor Stefan Forbes has a plethora of footage to carefully edit into a taut, intense 94 minutes. When we are not hearing from several of the participants in contemporary interviews, we’re thrust into the action courtesy of gorgeously shot real time footage. As policemen with itchy fingers wait to ambush the Black men who held up a sporting goods store, an increasingly larger crowd of pro-robber supporters grows behind them. Meanwhile, a negotiator races against time to avoid an impending massacre. Imagine if Sidney Lumet had been outside that Chase Bank in Brooklyn when the event that inspired “Dog Day Afternoon” was happening, and you have an idea of the level on which “Hold Your Fire” operates.

“Dog Day Afternoon” is mentioned by one interviewee because it depicted one of the two prior New York instances where there were negotiations between police and the men holding hostages. The other instance was the Attica Uprising, which Stanley Nelson chronicled in the superb, Oscar-nominated documentary, “Attica.” Attica ended with a raid by police that resulted in the killing of hostages and prisoners alike. Coincidentally, this is what Al Pacino’s character refers to when he screams “Attica! Attica” in Lumet’s film. The prison’s name had become a battle cry against police brutality in an era where law enforcement emulated the macho posturing of onscreen cops like Joe Friday, Dirty Harry and the NYPD’s own Popeye Doyle.

At least 30 minutes go by before one of the sparingly used onscreen intertitles announces that an explanation for the crime is forthcoming. The words “Why We Were There” appear onscreen before we return to Shu’aib Raheem, leader of the botched robbery. He and his cohorts, Dawud A. Rahman, Yusef Abdallah Almussadig, and Salih Ali Abdullah were all in their 20’s when they attempted to illegally procure guns from at John and Al’s Sporting Goods store in Williamsburg, Brooklyn on January 19, 1973. They were all Sunni Muslims, a rival group of the Nation of Islam. When Raheem became critical of the NOI, he is subjected to threats of violence he believes is coming from them. The 1973 Hanafi Muslim massacre, which occurred the day before, convinced him that his family was marked for death. “Had he gone to Nassau County,” says one of the talking heads, “he could have gotten a legal gun there. He had no criminal record.”

Jerry Riccio was behind the counter at John and Al’s when Raheem and his crew entered. Riccio is the most colorful character in “Hold Your Fire,” a no-nonsense New Yorker whose recounting of his ordeal has all the marks of a true storyteller. While Raheem rivets us with his explanations, feelings, fears and remorse, Riccio provides an equally engrossing counterpoint describing how he managed to escape with the hostages. He also describes the men, repeatedly referring to Dawud Rahman as “the little guy” who doesn’t say much and seemed to be actively fighting his own guilty feelings. Rahman is also interviewed, and he seems as soft spoken as Riccio described. When Riccio discovers Rahman is still in jail, his surprising response is one of empathy and concern.

“Hold Your Fire” examines the cop culture that equated masculinity with acts of violence and a lack of empathy by letting the cops who were there share their own thoughts. They’re split into two camps, one of which is led by the film’s hero, Harvey Schlossberg. Schlossberg was a traffic cop who had a Ph.D in psychology. Thanks to him, the NYPD became the first police force to have the modern era hostage negotiation department. Schlossberg was the negotiator on site who, along with future NYPD Commissioner Benjamin Ward (the first Black person to hold the title), tried to convince the force to try his nonviolent, psychologically based methodology. Behind a very cluttered desk, the negotiator cuts a very calming figure while explaining how he can hook the person on the other side of the phone. At one point, he gets Raheem’s mother to deliver a message from outside to him.

In the other camp are several officers who have no time for communicating with criminals. “Kill ‘em all, let God sort ‘em out,” says one. Schlossberg is referred to as “fruity,” “a pantywaist” and “a consummate Jew.” That last comment may have been some kind of compliment, but the former two are blatantly homophobic. Even worse, one officer says, with a straight face, that “there’s no racism in the police department.” Of course, he blows up his own argument by spouting some really racist bullshit immediately afterward. Forbes’ camera seems to brace for impact before this happens. Still, this is one side of the story and “Hold Your Fire” stands back so that it may be told.

The 1973 New York City Hostage Incident lasted 47 hours, which included multiple attempts at negotiating and numerous instances of gunfire that wounded Almussadig and killed an officer. It ended with the daring escape of the hostages and an at-the-time unprecedented peaceful surrender. Even the cops who thought Schlossberg was a wimp acknowledge on camera that they were surprised his plan worked. Capt. Al Baker notes “it was revolutionary. We started to transcend street justice … It’s an internal strength, the opposite of the eternal, explosive strength. That’s true manhood. Violence is a weakness.”

And yet, there was enough psychological damage to the hostages that they were permanently altered. We hear from hostage Rosemary Catalano, who watches footage of her escape with a stunned hesitance, and from Alice Buckner, who tells a heart-wrenching, sad story about her mother’s health decline before and after she escaped from the store with Catalano and Riccio. Forbes shows Raheem watching Buckner’s footage, and his reaction feels genuinely contrite. The interweaving of narratives is this film’s strongest asset. It also benefits from its quick pacing and the time capsule views of the New York City I knew as a kid, complete with WPLJ 95.5 ads on the sides of those ugly old MTA buses.

Like Garrett Bradley’s “Time,” “Hold Your Fire” does not let its subjects off the hook—they did the crimes for which they were arrested. However, both films cast a wider net to interrogate and even indict the systems that contributed to their downfall, systems that are still in place today. As in Nelson’s “Attica,” Forbes takes a look at the violent, racially tinged relationship between the police and the people they protect and serve. The mostly White officers have a pre-conceived notion of the Black people in their precincts, leading to massive distrust between the two parties that remains to this day. The most heartbreaking moment in the film is Mrs. Buckner’s refusal to be released early in the siege because she was more distrustful and afraid of the cops than the criminals who had her at gunpoint. By her rationale, she had less of a chance of getting shot if she stayed a hostage.

“Hold Your Fire” closes with a credit that says that Schlossberg’s methods are barely taught now, a sad coda that stings with a sense of regression. Forbes does leave us with some hope, showing that people on either side of the law can change themselves and the world around them for the better. My only complaint is that I wanted more scenes of the negotiation process itself, though I acknowledge I’m in the minority when it comes to enjoying that level of minutiae. Regardless, this is one of the year’s best films.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.