It was that legendary Chicago film exhibitor Oscar Brotman who gave me one of my most useful lessons in the art of film-watching. “In ninety-nine films out of a hundred,” Brotman told me, “if nothing has happened by the end of the first reel É nothing is going to happen.” This rule, he said, had saved him countless hours over the years because he had walked out of movies after the first uneventful reel.

I seem to remember arguing with him. There are some films, I said, in which nothing happens in the first reel because the director is trying to set up a universe of ennui and uneventfulness. Take a movie like Michelangelo Antonioni’s “L’Avventura,” for example.

“It closed in a week,” Brotman said.

“But, Oscar, it was voted one of the top ten greatest films of all time!”

“They must have all seen it in the first week.”

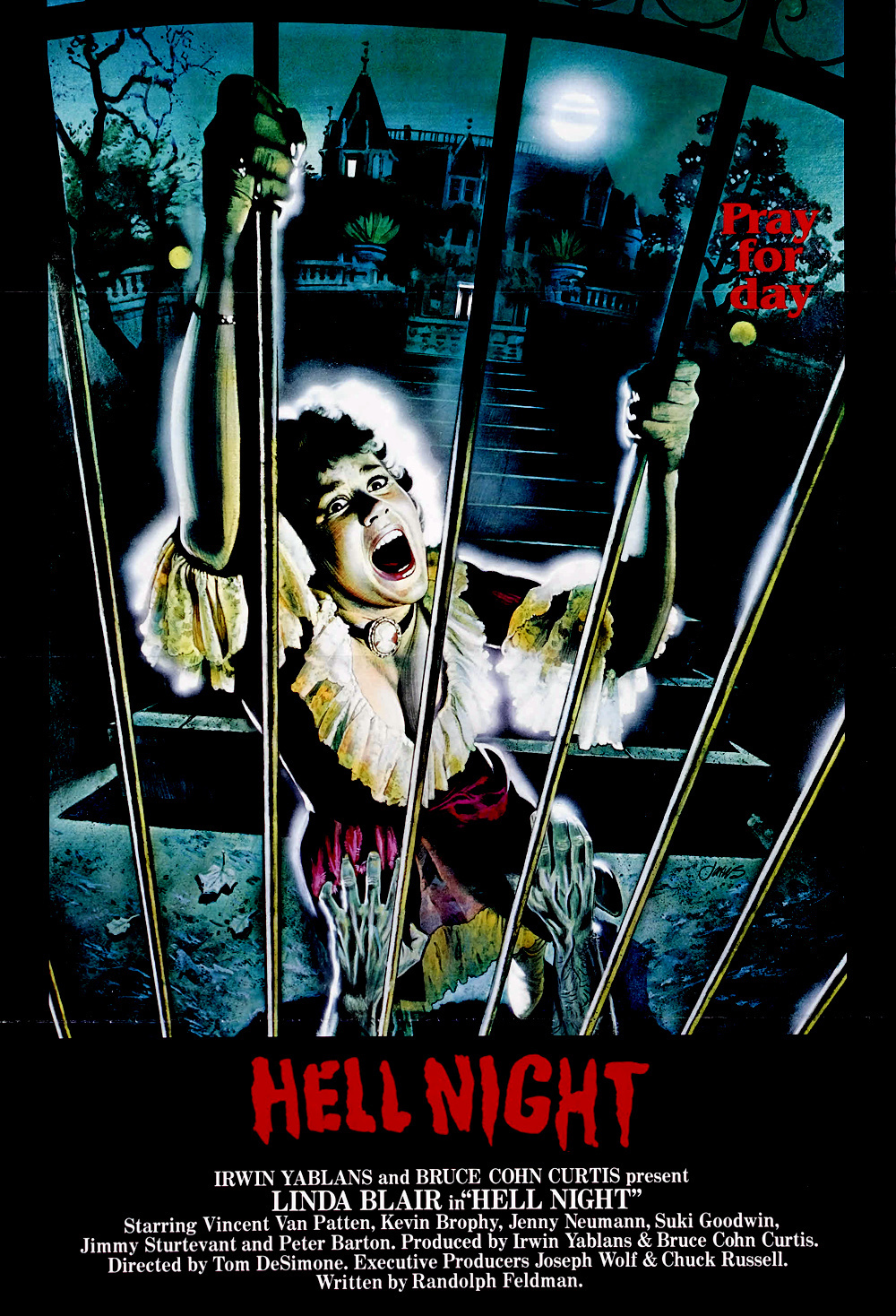

I was running this conversation through my memory while watching “Hell Night.” You know a movie is in trouble when what is happening on the screen inspires daydreams. I had lasted through the first reel, and nothing had happened. Now I was somewhere in the middle of the third reel, and still nothing had happened. By “nothing,” by the way, I mean nothing original, unexpected, well-crafted, interestingly acted, or even excitingly violent. “Hell Night” is a relentlessly lackluster example of the Dead Teenager Movie. The formula is always the same. A group of kids get together for some kind of adventure or forbidden ritual in a haunted house, summer camp, old school, etc. One of the kids tells a story about the horrible and gruesome murders that happened there years ago. He always ends the same way: “, and they say the killer never died and is still lurking here somewhere.” That was the formula of “The Burning” and the “Friday The 13th” movies, and it’s the formula again in “Hell Night.”

This time, the pretext is a fraternity-sorority initiation stunt. The venue is an old mansion. We learn that the hapless Garth family once lived there and had four deformed and handicapped children. The misfortunes of the children are described in great detail, with dialogue that’s in very bad taste. But then of course “Hell Night” is in bad taste. The only child that need concern us is the youngest Garth, who was named Andrew and was born, we are told, a “gork.” None of the dictionaries at my command include the word “gork,” but for the purposes of “Hell Night” we can define “gork” thus:

Gork (n.) Deformed, violent creature that lurks in horror movies, jumping out of basement shadows and decapitating screaming teenagers.

I have now of course, given away the plot of “Hell Night.” As the fraternity and sorority kids creep through passageways of the old house, their candle flames fluttering in the wind, Andrew the Gork picks them off, one by one, in scenes of bloody detail. Finally only Linda Blair is left. Why does she survive? Maybe because she’s a battle-hardened veteran, having previously more or less lived through “The Exorcist,” “Exorcist II: The Heretic,” and “Born Innocent.” At least in those movies, something happened in the first reel.