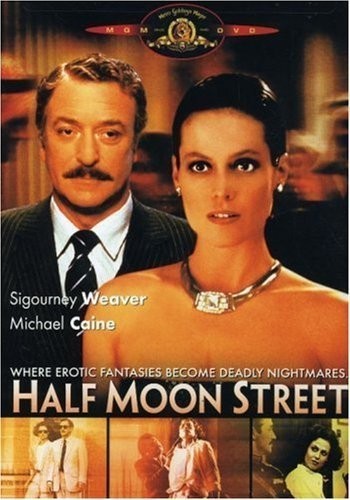

I was reflecting, as the lights went down before “Half Moon Street,” that I could not recall a single bad performance by either of the stars, Michael Caine and Sigourney Weaver. Caine’s record is all the more remarkable because he has emerged untouched from some of the worst movies of the last 20 years with his unshakable self-confidence and quiet good humor. In a certain sense, it didn’t even matter what “Half Moon Street” was about, or whether it was much good, because I was so curious to see what Caine and Weaver would be like together.

The movie stars Weaver as the wonderfully named Dr. Lauren Slaughter, an American academician who specializes in China and works for a cold-war think tank in London. She is tall, smart, calculating and concerned with her own advantage. When she writes an article for the potty general who runs her organization and it turns up in the Spectator under his name, she doesn’t go along with the program: She lets him know he’s a spineless pig. And when she reflects that she is doing the work of her inferiors for starvation wages, she takes action.

It happens this way: She meets a man at a party, and he sends her a videotape documentary about a high-priced call-girl agency. She looks at the tape, considers the possibilities and goes to interview for a job. She is completely open about the whole thing. She entertains clients using her real name, and when she is asked at an academic gathering what she does with her evenings, she replies that she has dinner with rich men.

One night she recognizes one of her clients. He tries to introduce himself as Sam Weller, but she has read her Dickens, smiles at that and calls him by his name – Lord Bulbeck. He is a government spokesman on defense in the House of Lords and a lonely man who lives alone in a large house and says he doesn’t have the time to find sex and companionship through the ordinary channels.

That’s fine with her. They make love, start talking, begin to like one another and before long, they have crossed over that great divide between asking each other what they like in bed and asking each other how they like their omelets. There is a certain instant compatibility between them. They are both friendly and outgoing people with something cold at their cores, and the device of the escort agency rather suits them: It provides a reason why they are in bed that does not involve such complicated issues as love and affection.

Slaughter meets other clients, including rich Middle Easterners who set her up in an expensive flat in Mayfair. She continues to work at the think tank, where she doesn’t much mind that certain people know about her moonlighting. Bulbeck gets involved in tricky negotiations involving a Middle East peace settlement, and of course the Special Branch monitors all of his activities. It checks out Slaughter and eavesdrops on his private moments, and that is as it should be.

What makes “Half Moon Street” so intriguing up to this point is the literal and almost offhand honesty that grows between the Weaver and Caine characters. Their feelings are clear, their motives are clear, and with their eyes wide open they’re falling in love.

This whole aspect of the movie is essentially the contribution of the director, Bob Swaim, and his co-writer, Edward Behr. In Paul Theroux’s original novel, Doctor Slaughter, Bulbeck was older and less amusing, and Slaughter was very alone in the world she had made for herself. The love that grows between the bright young woman and the gentle middle-aged man provides a subject that wasn’t there in the Theroux version, and so it’s sort of a shock when the plot reintroduces itself.

The plot has to do with Middle Eastern intrigues, spy rings, terrorists and plans to sabotage Bulbeck’s peace initiative. And it leads to the movie’s closing sequences, in which we lose the particular charms of the growing romance and find ourselves back in those familiar movie cliches where everything is settled with violence. God, it’s boring to have to wait through an obligatory series of scenes until all of the right people have been killed and the movie can be over.

The last scene in “Half Moon Street” is particularly unconvincing, because for a long time this movie seemed so unorthodox that I expected a tough and realistic ending in which at least one of the wrong people would get killed. No such luck. And so I was right: The movie is interesting primarily because of the interaction between Weaver and Caine. Swaim deserves credit for the intelligence and wit of the first 80 or 90 minutes, but must also take the blame for the ending, which is a complete surrender to generic conventions.