Regaled for 50 years by the stupendous idiocy of the American version of “Godzilla,” audiences can now see the original Japanese version, which is equally idiotic, but, properly decoded, was the “Fahrenheit 9/11” of its time. Both films come after fearsome attacks on their nations, embody urgent warnings, and even incorporate similar dialogue, such as “The report is of such dire importance it must not be made public.” Is that from 1954 Tokyo or 2004 Washington?

The first “Godzilla” set box office records in Japan and inspired countless sequels, remakes and rip-offs. It was made shortly after an American H-bomb test in the Pacific contaminated a large area of ocean and gave radiation sickness to a boatload of Japanese fishermen. It refers repeatedly to Nagasaki, H-bombs and civilian casualties, and obviously embodies Japanese fears about American nuclear tests.

But that is not the movie you have seen. For one thing, it doesn’t star Raymond Burr as Steve Martin, intrepid American journalist, who helpfully explains, “I was headed for an assignment in Cairo when I dropped off for a social call in Tokyo.”

In the ’50s, the American producer Joseph E. Levine bought the Japanese film, cut it by 40 minutes, removed all of the political content, and awkwardly inserted Burr into scenes where he clearly did not fit. The hapless actor gives us reaction shots where he’s looking in the wrong direction, listens to Japanese actors dubbed into the American idiom (they always call him, “Steve Martin” or even “the famous Steve Martin”), and provides a reassuring conclusion in which Godzilla is seen as some kind of public health problem, or maybe just a malcontent.

The Japanese version, now in general U.S. release to mark the film’s 50th anniversary, is a bad film, but with an undeniable urgency. I learn from helpful notes by Mike Flores of the Psychotronic Film Society that the opening scenes, showing fishing boats disappearing as the sea boils up, would have been read by Japanese audiences as a coded version of U.S. underwater H-bomb tests. Much is made of a scientist named Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), who could destroy Godzilla with his secret weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer, but hesitates because he is afraid the weapon might fall into the wrong hands, just as H-bombs might, and have. The film’s ending warns that atomic tests may lead to more Godzillas. All cut from the U.S. version.

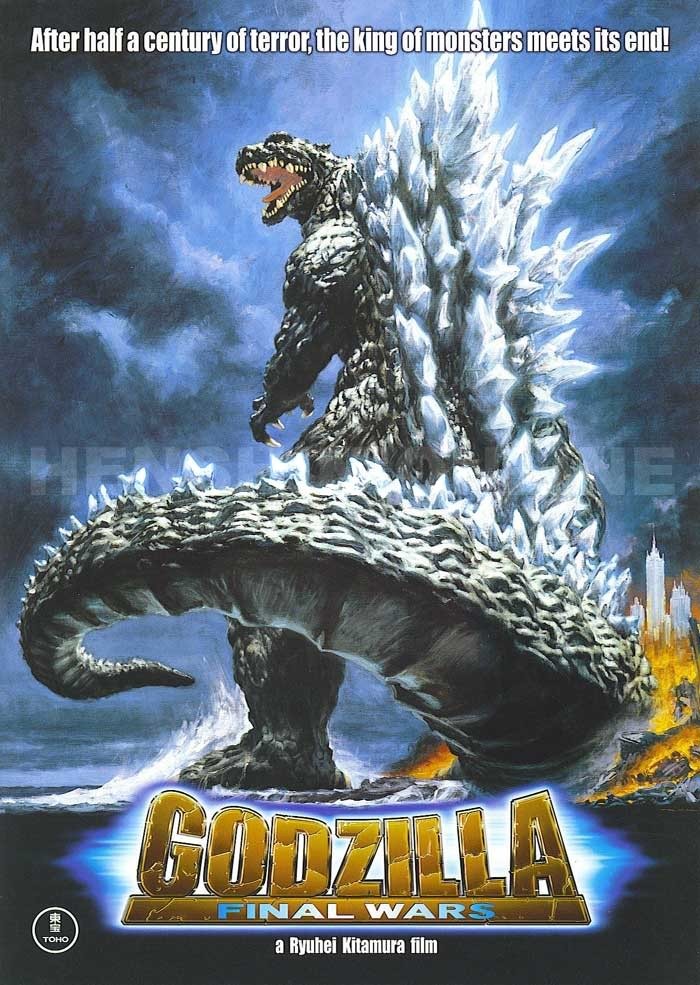

In these days of flawless special effects, Godzilla and the city he destroys are equally crude. Godzilla at times looks uncannily like a man in a lizard suit, stomping on cardboard sets, as indeed he was, and did. Other scenes show him as a stuffed, awkward animatronic model. This was not state of the art even at the time; “King Kong” (1933) was much more convincing.

When Dr. Serizawa demonstrates the Oxygen Destroyer to the fiancee of his son, the superweapon is somewhat anticlimactic. He drops a pill into a tank of tropical fish, the tank lights up, he shouts “stand back!,” the fiancee screams, and the fish go belly up. Yeah, that’ll stop Godzilla in his tracks.

Reporters covering Godzilla’s advance are rarely seen in the same shot with the monster. Instead, they look offscreen with horror; a TV reporter, broadcasting for some reason from his station’s tower, sees Godzilla looming nearby and signs off, “Sayonara, everyone!” Meanwhile, searchlights sweep the sky, in case Godzilla learns to fly.

The movie’s original Japanese dialogue, subtitled, is as harebrained as Burr’s dubbed lines. When the Japanese Parliament meets (in what looks like a high school home room), the dialogue is portentous but circular:

“The professor raises an interesting question! We need scientific research!”

“Yes, but at what cost?”

“Yes, that’s the question!”

Is there a reason to see the original “Godzilla”? Not because of its artistic stature, but perhaps because of the feeling we can sense in its parable about the monstrous threats unleashed by the atomic age. There are shots of Godzilla’s victims in hospitals, and they reminded me of documentaries of Japanese A-bomb victims. The incompetence of scientists, politicians and the military will ring a bell.

This is a bad movie, but it has earned its place in history, and the enduring popularity of Godzilla and other monsters shows that it struck a chord. Can it be a coincidence, in these years of trauma after 9/11, that in a 2005 remake, King Kong will march once again on New York?