I think the first time I saw Gilbert Gottfried was in 1980, on “Saturday Night Live.” I was 21 years old and I did not make a habit of watching “Saturday Night Live,” as cool New Wave 21-year-olds did not as a rule make a habit of staying in on Saturday nights, so I’m guessing I was watching because Captain Beefheart was the musical guest. Gottfried was on one of the Ur-“Weekend-Update” segments—good grief was it “The Rocket Report?”—and he was complaining about the (imagined) anti-Semitism of some of the other sketches on the show. Indignantly, he screeched, “Who writes this stuff—HITLER?” Instant catchphrase time. While I never became a devotee of comedy clubs, I’ve been a fan since.

So I expected to enjoy “Gilbert,” a documentary about Gottfried directed by Neil Berkeley, a lot more enthusiastically than I ended up doing. The linchpin of the film is the difference between Gilbert’s outrageous, boundary-testing (both in terms of material and delivery) comedy style, and his relatively stable, loving, and ostensibly unexpectedly wholesome home life, which he shares with his wife of ten years, Dara Kravitz, and their two small children.

Gottfried’s latter-day fame is two-fold. On the one hand, he is kind-of-beloved for his Disney work, playing the role of a wisecracking parrot in “Aladdin” and its various video and videogame spinoffs. And, of course, he was once the health-insurance hawking Aflac duck, until a series of supposedly insensitive jokes about the Japan tsunami of 2011 Gottfried posted on Twitter got him fired from that lucrative (and easy-sounding) gig. Speaking of insensitive jokes, the other prong of his celebrity stems from his making a 9/11 joke before people were even calling it “9/11,” in late September of 2001, at a roast for Hugh Hefner. Here the modern usage of “too soon” was coined, and Gottfried responded to the boos by breaking out the inside-comedy-baseball joke whose punchline is “The Aristocrats!” Said joke became the subject of a breathtakingly hilarious 2005 documentary, called of course “The Aristocrats.”

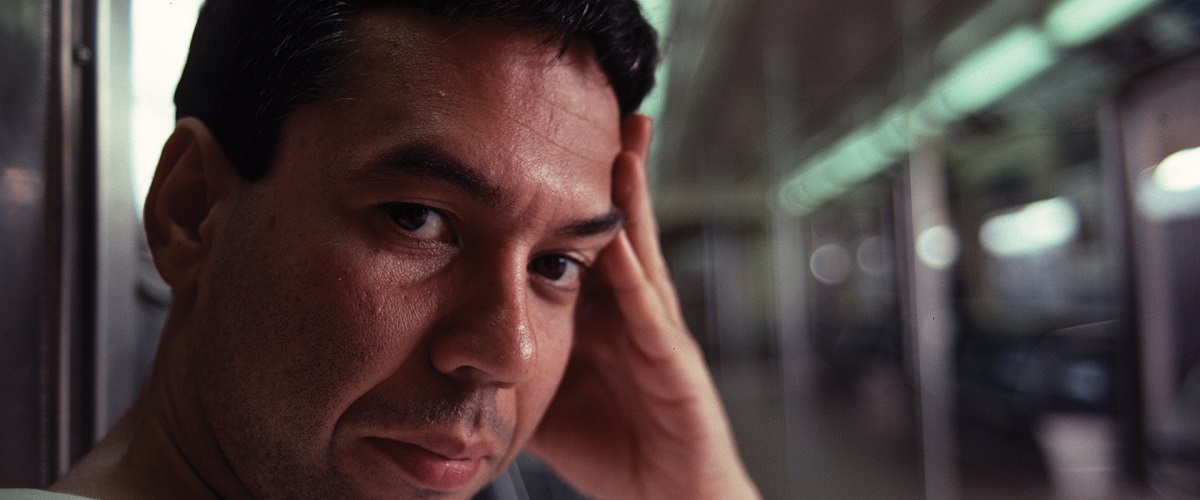

Gottfried’s comedy is often shocking. As in, it compels you to drop your jaw in disbelief. There’s a scene in this movie of him doing standup and he begins a bit by saying “I was reading a memoir by Mackenzie Philips,” and boy oh boy even if you think you know where he’s going with it, where he ends up is conceptually even worse. And yet, God help him and God help me, it’s funny. (Also funny: the snapshots of Gottfried from his pre-comedy years, when he was an avid yoga practitioner with a mustache. He looks like a nerdier Carlos Santana.)

Because of this, I suppose the viewer is supposed to be incredibly surprised to see his nice, orderly apartment, meet his kind, attractive, smart wife, see his well-mannered and well-dressed children. And maybe I would have been had I not already read more than one profile of Gottfried that described him speaking without the affectations he applies when performing, or noting that he has all these normal things in his life. Performers are different in real life than on stage. Even Andy Kaufman had to get up and brush his teeth in the morning.

The movie does give close scrutiny to some of Mr. Gottfried’s more authentic eccentricities. “He’s the cheapest comedian I’ve ever met,” says colleague Anthony Jeselnik, and there’s a funny sequence showing Gottfried waiting for a bus to take him to a gig out of state. He actually does some washing in his hotel sink. And he hoards hotel soap and deodorant, which I reckoned was the weirdest thing about him besides his imagination.

While the other stuff offered up by relatives and colleagues is not uninteresting, it’s also not uncommon. Comedians are damaged people, yes; they often come from homes where affection and respect was withheld, yes; doing standup is grueling work, yes. One of the on-screen interviewees, Paul Provenza, hits on something relevant when he says, “Who’s not from some kind of damaged background? Firemen are damaged people, too.”

That said, the insights offered from the almost two-dozen show biz luminaries are not always commonplace, and Gottfried is always an interesting screen presence, even when he’s far removed from his persona. And even when he IS far removed from his persona, he’s still a guy who’s likely to yell, or at least mutter, “Get off my lawn” at some unspecified point in the future. Probably when he buys a piece of property that has a lawn.