“We don’t always choose our adventures,” wrote Barry Corbet. “Adventures often befall us.” He advised readers to “see everything as an adventure.” And he urged them to give to the world “extravagantly.”

This advice comes at the end of his 1980 book, Options: Spinal Cord Injury and the Future. When he wrote it, Corbet thought of his life in two chapters. In chapter one, he was in the first team of Americans to climb Mount Everest, made the first ascents of Antarctica’s highest and second-highest peaks, and set many other records in mountain climbing. His second chapter followed a helicopter accident in 1968, which left him with a severe spinal injury.

At that time, just 50 years after sulfa drugs and antibiotics first made it possible for people with lower body paralysis to survive more than a few months, before the Americans with Disabilities Act and more recent developments in physical therapy and rehabilitation, Corbet was released from the hospital without any plan for occupational therapy or anyone suggesting he might find his way to a meaningful life. The most touching parts of this documentary are learning how Corbet, who died in 2004, gave others what he was not given: a road map for moving forward after spinal injury, physically, emotionally, and, at least for some, spiritually. At his life’s end, Corbet realized it was all one chapter.

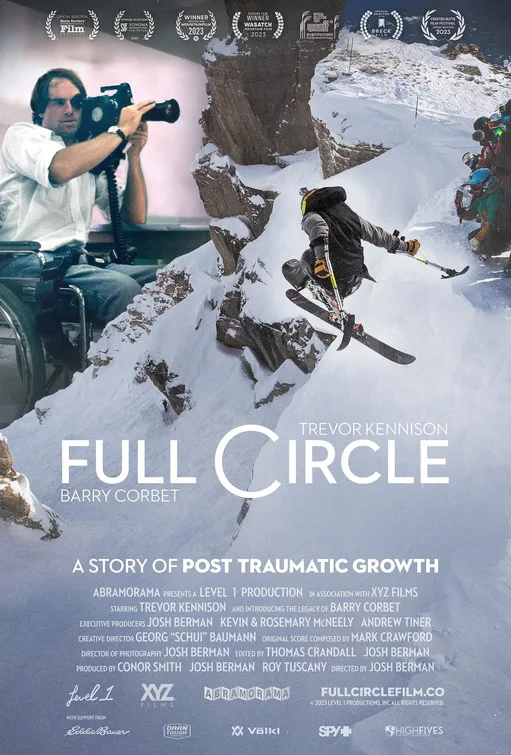

“Full Circle” twins Corbet’s story with that of Trevor Kennison, who injured his spine attempting a 40-foot ski jump in 2014. Kennison is the beneficiary of the efforts by Corbet and others to give those with severe spinal injuries opportunities to make the most of their abilities and their lives. Kennison learns to develop satisfying goals and set new records. He plans for a spectacular stunt at the location of his accident. We see how the two core principles of his previous life–determination, and daredevil risk–continue to be his foundation. Most people with major spine trauma initially focus on walking as a goal because it would be a return to what they could do before. But we learn, as Trevor does, that when that is not possible, other goals, some exceeding what they considered possible before, can be even more satisfying.

Kennison wants to exceed what anyone considered possible for any athlete, even fully abled. The thought of being the first sit-skier to do a double-back flip off a ski jump makes him feel alive and powerful. In Corbet’s words, “What was impossible yesterday is today’s absolute limit and tomorrow’s commonplace.” Kennison is not a disabled athlete; he is just an athlete. Before his accident, he was a plumber who loved to snowboard. Afterward, he became something beyond his imagination before the accident, a full-time athlete with sponsors.

The film begins with the overlap of our two lead characters as Kennison is about to compete on one of the most difficult ski runs in North America, if not the world. The run, a steep, narrow chute that drops nearly 30 feet straight down, is named for the person who discovered it: Barry Corbet. The event is called Kings and Queens of Corbet’s. It is a rare competition founded, run, and judged by athletes. We hear those in charge describe its dangers: “Almost everybody [who looks down the steep gully of Corbet’s Couloir] is like, ‘No, I’m good.’” They tell us their concerns about a sit-skier participating: “Was I going to allow him into the competition to watch him die?” But they decide it is more important to boost his confidence by telling him they believe in him, with “See you on the other side of this paradigm-shifting thing you are about to do.”

The film’s two stories are not always smoothly integrated because the two men are so different, and their connection is tenuous. The mix of styles onscreen works better. Some sections of the film have a handmade, home movie feel, with the GoPro shots from Kennison’s helmet camera and intimate footage of private moments, including his adaptations for bathroom and sexual functions. The audio in the GoPro footage includes Kennison’s jubilant scream at completing his double spins, a sound so visceral and pure it coveys even more than the image. In other scenes, the quiet grandeur of the mountain settings emphasizes the challenges for an athlete creating stunts that feel like winning a competition with nature.

Colorado’s Craig Rehabilitation Hospital, specializing in people with spinal injuries and featured in the film, has a motto: “Redefining possible.” But the most significant redefined word in the film is replacing “disabled,” with its focus on what cannot be done, with “adaptive,” and its sense of unlimited possibilities.

Now playing in theaters.