Jean-Paul Sartre’s play “No Exit” premiered in May 1944, while his beloved Paris was under Nazi occupation. To skirt the occupiers’ curfews, the play is just one act, in which three characters find themselves in a very different version of hell than they expected. Each character watches the events following their death in the world they left behind, observing his or her memory blink out on earth, as those who knew them gradually forget. They’d died once, deceased and mourned, but now they’re truly dead—as if they’d never existed.

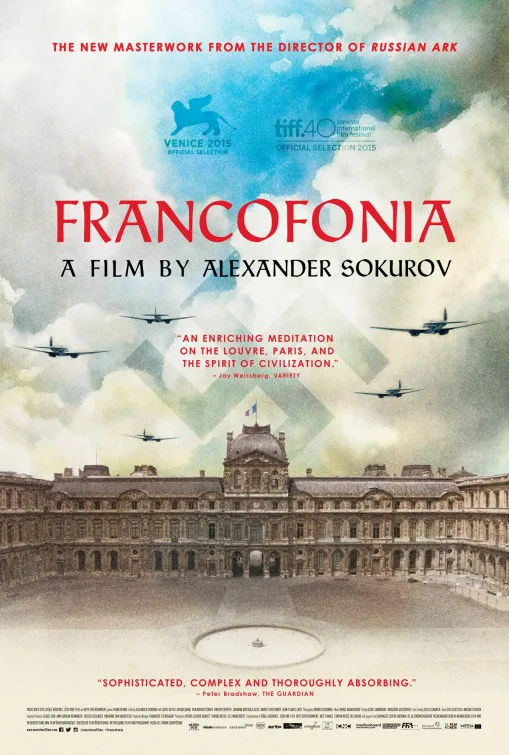

While Sartre wrote plays and books and argued with his circle of buddies at Le Dôme Café in occupied Paris, a great deal of human culture was in danger of both kinds of death. After all, if London can be bombed, so can Paris—home of the Louvre, the massive treasure trove of culture from Europe, Greece, Rome, and the ancient Near East. That weight of history and the danger we all narrowly escaped when Paris was occupied is Alexander Sokurov’s main interest in “Francofonia”—even more than the beauty contained in the Louvre, upon which any filmmaker would be excused for fixating.

Sokurov’s 2002 film “Russian Ark,” shot in one 96-minute Steadicam sequence, was similarly interested in the history of the Winter Palace (now part of St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum) and so it collapsed its long-past events and characters into one continuous take of the building. For “Francofonia,” Sokurov returns to the art museum, but perhaps taking a cue from its Parisian setting, this film wanders like a flâneur between past and present, traversing space and history, crossing from fiction to nonfiction and back. The Louvre is both a warehouse for culture—including the spoils of war—and an artifact of its own long history, and that’s the subject of reverence: a record of humankind’s efforts to imprint itself upon time. So Sokurov takes a similar approach. He treats the screen like a canvas, splitting it in half, playing with shadows and colors on old photographs, gliding along the long Louvre hallways, changing film stock and color gradations, dropping representation out altogether to let colors fade into one another.

As World War II loomed, many of the paintings were removed from the Louvre and squirreled away in various châteaux, far from likely sites of destruction and out of the reach of roving bands of Nazi soldiers. The empty frames and sculptures were all that remained. Sokurov shows photos to us of that strange empty Louvre—or perhaps depicts what it would have looked like; it’s hard to tell when the image on screen is an original and when it’s a recreation, created since (as he points out) archival footage and photographs “can conceal the improper behavior of power and people.” In footage from that time, everyone looks happy. The real story is in what we can’t see.

If you just watch the masses of tourists wandering beneath the giant glassy pyramid that sits above the Louvre’s central, most of whom are headed for the Mona Lisa, you forget that the Louvre was once a palace, built to be a fortress in the late 12th century. In a signature bit of camera trickery, at one point Sokurov puts us on a tower high above the museum and makes a full rotation, erasing the present and giving us the long-distant past: forests, trees, a few rudimentary buildings. Eventually, we see the palace spring up and change shape in its frequent alterations, eventually giving way to the more familiar courtyard and palace. Sokurov is the film’s narrator (mostly in Russian), but to accompany us down the corridors of the empty museum, he conjures two ghosts: Vincent Nemeth’s comical Napoléon Bonaparte (under whose rule the Louvre’s collection dramatically increased), who declares “c’est moi!” to us no matter what painting he’s pointing at; and Joanna Korthals Altes’ Marianne, symbol of the French Republic, clad in a Greek chiton and a red Phrygian cap, who whispers “Liberte! Fraternite! Equalite!” as she glides down hallways.

Sokoruv bends the film around the Louvre’s most recent period of peril, the Nazi occupation of 1940-1944. But nothing went quite as expected. Paris was not bombed. The Louvre was, in fact, preserved. It seems at least part of the reason is the unlikely partnership that sprung up between Jacques Jaujard (played in the film by Louis-Do de Lencquesaing), director of the Louvre and all national museums, and the German officer Count Franziskus Wolff-Metternich (Benjamin Utzerath). Both men were nearly the same age, and as dramatized in “Francofonia,” they worked together to ensure that the treasures were treated with respect—and so we encounter the unlikely sight of Nazi soldiers looking at sculptures in the museum’s grand hallways, and even a bomber plane, in what must be an imagined moment, flying through the Cour Marly.

True, the preservation of art was partly a play for power, a gratuitous display of benevolence by an occupying force, even if it was spearheaded by a man who seems to have been uncommonly sensitive to aesthetics and history. But even with Jaujard and Wolff-Metternich’s efforts, some art was lost. Bearing precious art as cargo, some ships sank to the bottom of their trade routes. Sokurov uses this fact to bookend the film, because his central interest is not the grand events of history, but the humans fixed in it, given some measure of immortality in the faces of paintings, sculptures, and photographs—the “human stock of Europe,” as he puts it. “What would have happened to the history of Europe if portraiture had not appeared?” he asks. At the Louvre and in “Francofonia,” we are always looking into the faces and eyes of the long-dead, not just of Europe but of other civilizations, too (the recently restored 2nd-century Greek “Winged Victory of Samothrace,” which lacks a head but projects enormous presence nonetheless, makes an appearance).

Last summer, during a six-week stay in Paris, I went frequently to the Louvre, my lengthy sojourn providing the unusual luxury of sitting in one gallery for a long time and watching the visitors without worrying about missing anything. When you’re not moving with the crowd, you can watch them, and I watched faces: small children looking up at the giant paintings in wonder, bored couples grimly stalking through the halls because a guidebook told them to go, art students and elderly novices sketching sculptures. The largest group of visitors was comprised of enthusiastic tourists on a headlong rush through the corridors, holding up iPhones and not bothering to look at individual works for even a second before snapping pictures of everything.

I confess that I felt annoyed and smug about their Philistinism, but watching “Francofonia” it occurred to me that their masses of digital photographs are a way of preserving faces and history, and whether or not they ever look at them again (the likelihood is very low), they’ve preserved the faces. History has been replicated. As long as those photos remain, the old history never blinks out of memory entirely, as if it never existed, with no one to remember it. Near the film’s end, Sokurov-as-narrator breaks the fourth wall and tells Wolff-Metternich and Jaujard what the events of their futures will be—both of them fated to eventual obscurity and basically forgotten, at least until Sokurov revived them here. “Time is a tight knot,” he says. It is at least one duty of art to make sure it doesn’t unravel.