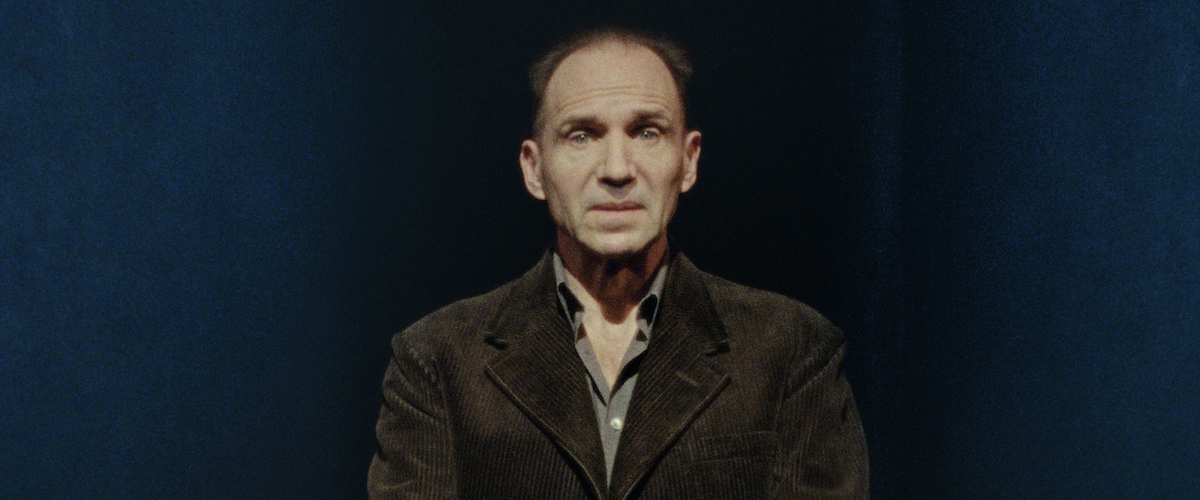

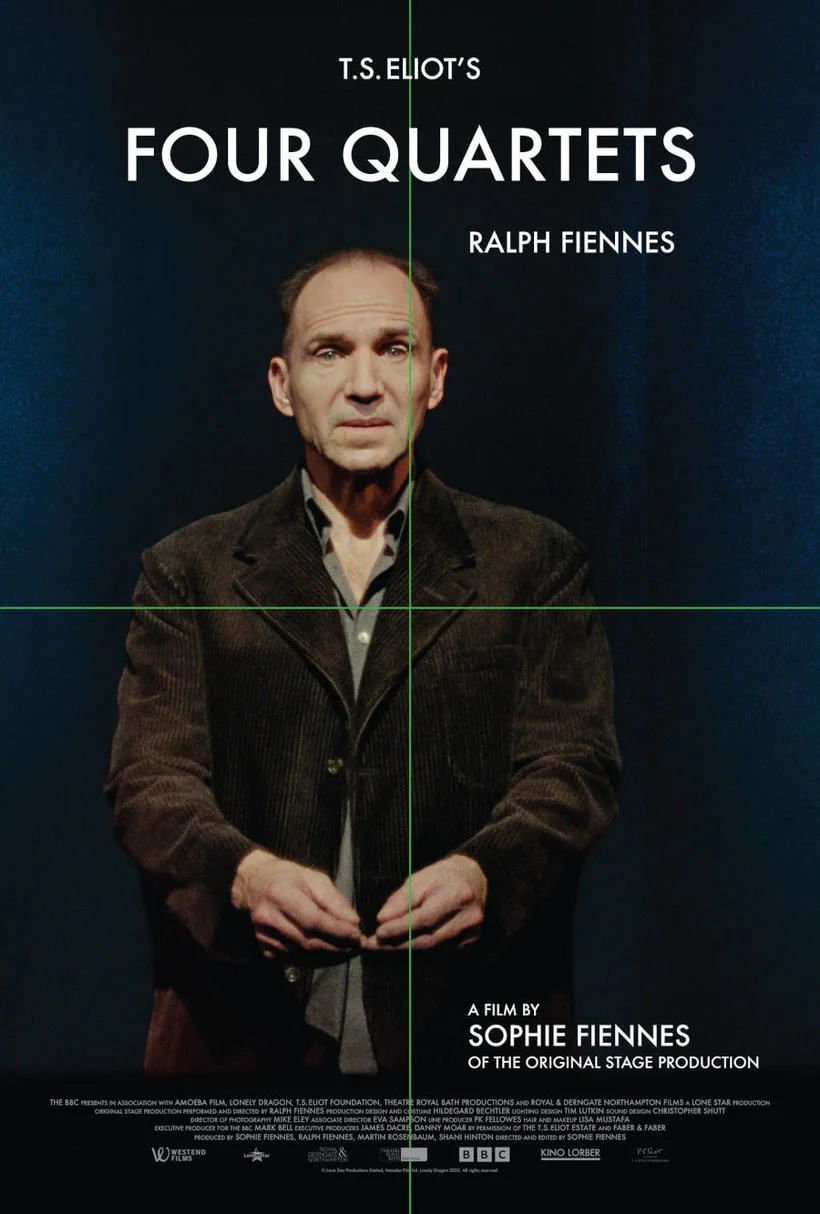

Conceptually ambitious, lyrically dazzling, and famously opaque, T.S. Eliot’s poem Four Quartets challenges us from the very beginning with quotes from Heraclitus – in Greek. Ralph Fiennes recited the entire poem in a one-man stage show, directing himself. His sister, Sophie Fiennes, directs the film version. It is still very much a theater piece, presented simply. Except for a few brief glimpses of the outdoors, it is just an actor speaking from a stage. He is plainly dressed and barefoot. There is a chair and a table. And Eliot’s words in Fiennes’ classically trained voice.

Let’s start with the poem. I’ve got good news for you, if struggled with it in school or on your own because it’s considered one of the most significant literary works of the 20th Century or maybe just because you liked Cats and thought you’d like to see what else Eliot has to say, without the Andrew Lloyd Webber music and sinuous dance numbers. It’s not just you. Four Quartets was not initially conceived or published as one poem, and indeed some of its language was originally written for earlier drafts of other works. It is very abstract, but there are specific references to specific places and events.

The four sections are each named for real places. The first one is named for Burnt Norton, a home with a garden that inspired some of the first stanza’s images. In my opinion, based on my extensive experience in literary critique in a couple of semesters in college, this poem has some spectacularly beautiful language and some arresting concepts, but let’s be honest, some of it would not make it as a fortune cookie, including our friend Heraclitus, whose quote Eliot uses as an epigraph: “The way up and the way down are one and the same.” Eliot continues in this vein with lines like, “The way up is the way down. The way forward is the way back.” “In my end is my beginning.” If you are confused, just think of it as one of those dishes made from leftovers that are not enough for a meal but could be combined into something else.

The poem considers eternal themes of time, meaning, and the divine, but should be read in the context of its era, the separate parts written from 1935-1944, as war loomed and then raged over Europe. That is the background of the poem’s agonizing grappling with existential worry. In one segment, we are reminded of that when Fiennes sits at a 1940s microphone as though he is speaking on the radio, in the background a strain of music from that era. While it suggests more than once that time and space can be an illusion, there is also a yearning for a future in the midst of dire peril. And there is also the possibility of gaining understanding. One of the most famous lines from the poem is near the end: “We shall not cease from exploration/And the end of all our exploring/Will be to arrive where we started/And know the place for the first time.”

Next, consider the performance. Throughout the film, as Fiennes speaks, he cajoles, urges, explains, teaches, asks, and prays. He stands. He sits on the chair. He sits cross-legged on the floor. He gestures. He dances, stomping on the stage. We may sometimes feel lost with the poem’s language, shifting from elliptical to impenetrable, mixing gorgeous lyricism with zen-like aphorisms. We may not understand it, but Fiennes persuades us that he does. He is utterly immersed in the poem, and he beckons us to join him there.

And now, consider it as a film. The sound design, with subtle sounds of waves and birds, enhances the mood, but some of the stage lighting effects might have been more effective in the theater than on the screen, and the brief cutaways to scenes of nature are more distracting than illuminating. We often hear people say about actors with beautiful diction that we would be willing to hear them read the phone book. I’d be willing to hear Ralph Fiennes read the phone book, but it is much, much better to hear him challenge us with these words. Poems should be alive, and listened to, not just confined to a page. And that is reason enough for Sophie and Ralph Fiennes to make this film and for people who love language and literature to see it.

That does not mean it is intended for everyone. I admit I broke the rules of movie-watching by keeping a copy of the poem on my lap, and now and then, I stopped the film to replay a line. I would recommend the same to anyone unfamiliar with the poem. For those who are open to its challenges, it is a meditation on time, loss, and connection, and almost a century later, those themes are just as vital as they were when Eliot wrote them.

Now playing in theaters.