John Singleton‘s “Four Brothers” is an urban Western, or maybe it’s an urban movie inspired by a Western; either way, it’s intended to be more mythic than realistic. It connects with underlying moral currents in the way Westerns used to, back before greed, fear, anger and “society” provided action movies with all the motivation they needed.

The movie opens with a sweet white-haired grandmother type who arrives at a Detroit convenience store late at night. Wrong store, wrong neighborhood, we’re thinking (was it only last week that somebody was gunned down in a store just like this in “November“?). But Evelyn Mercer (Fionnula Flanagan) has a reason to be there: A frightened young kid has been caught shop-lifting some candy, and she settles things with the store owner and puts the fear of God into the kid. Then two stickup guys walk into the store, and she is shot dead.

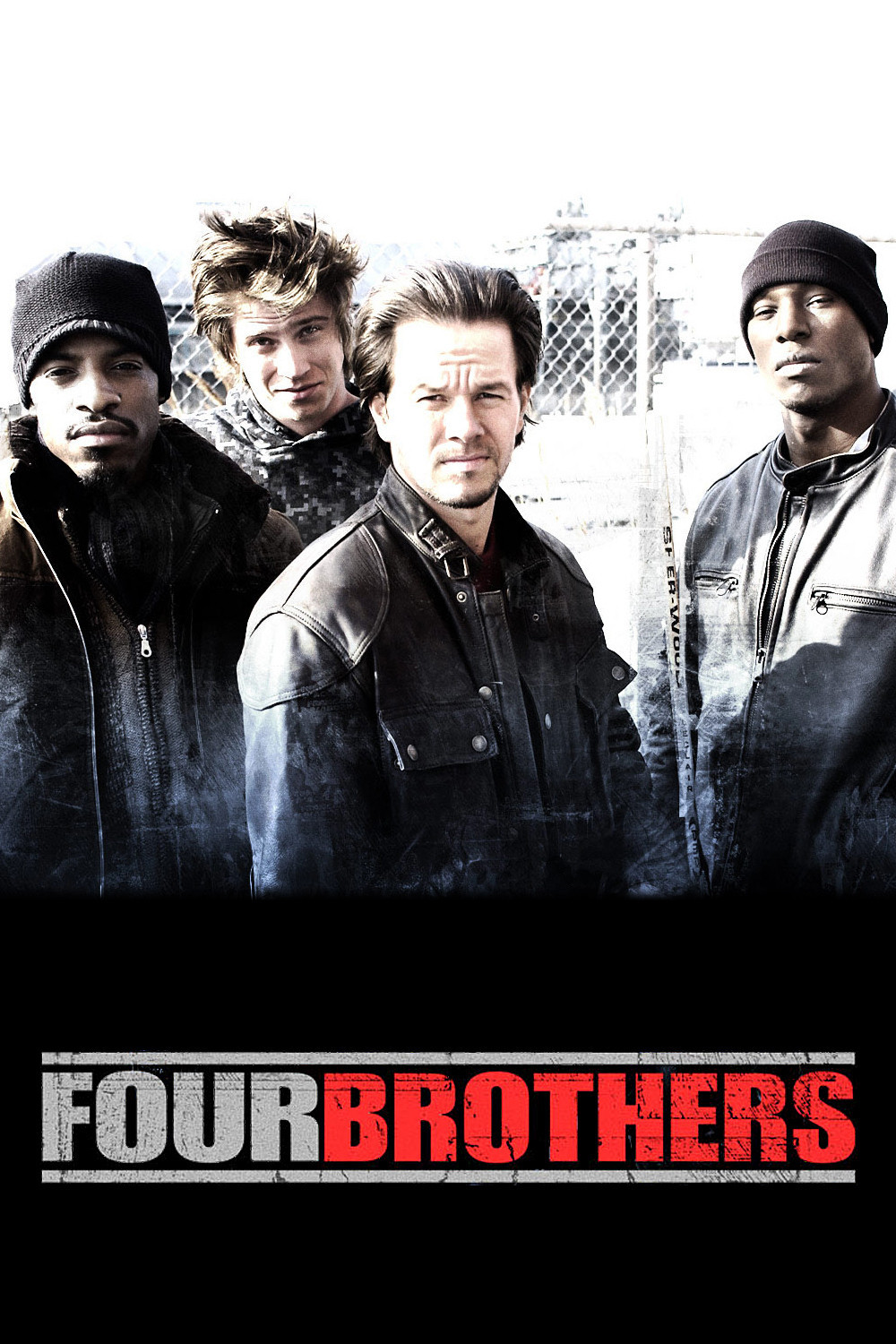

At the funeral, we meet her four adopted sons, two black, two white. She was a foster mother all of her life, and these were the only four she couldn’t find homes for: Bobby (Mark Wahlberg), Angel (Tyrese Gibson), Jeremiah (Andre Benjamin) and Jack (Garrett Hedlund). Bobby is the oldest, the natural leader, the one with a temper. Angel is the player with a hot babe (Sofi Vergara). Jeremiah is a success; he’s married (to Taraji P. Henson), has a family, is involved in real estate deals. Jack is a rock-and-roller.

They all have the name Mercer and they all consider Evelyn their mom, but they grew up on mean streets and have not spent a lot of time getting all sentimental about being “brothers.” That begins to change at the funeral, when they wordlessly agree that their mother’s death requires some kind of action. Jeremiah, the businessman, observes: “The people who did this are from the same streets we’re from. Mom would have been the first to forgive them.” True of Mom, not true of them.

This story is inspired by Henry Hathaway’s “The Sons of Katie Elder” (1965), unseen by me but cited by my fellow critic Emanuel Levy. (I am awed by the number of films I have seen, and awed by the number I have not seen.) At first it looks like an open-and-shut case: Witnesses saw two gang-bangers walk in and blast the store owner. Mom was a bystander, shot in cold blood. But as the brothers look at the tape from the security camera, they’re struck by how ruthlessly she was murdered; they turn up evidence suggesting maybe there was something more to this killing. As long as we’re talking about the influence of old movies, a crucial clue in “Four Brothers” involves when the lights are turned off on a basketball court; I was reminded of the almanac in John Ford’s “Young Mr. Lincoln” (1939) that provides the phases of the moon.

I won’t describe the rest of the plot, which unfolds like a police procedural, but I will note a nice touch involving the way Jeremiah looks guilty for a moment simply because he is successful and generous. And I’ll mention the key supporting characters. Terrence Howard and Josh Charles play the two cops on the case, and Chiwetel Ejiofor (“Dirty Pretty Things“), who is one of the nicest men alive, plays one of the meanest men in Detroit. He’s a crime boss whose methods for humbling his underlings pass beyond mere cruelty into demented ingenuity.

For John Singleton, the movie is a return to inner-city subjects after some fairly wide excursions (“Shaft,” “2 Fast 2 Furious“). In between those two he made the provocative “Baby Boy” (2001), which attacks some young black men who feel licensed to live at home with their mothers, thoughtlessly father children, avoid work, and perpetuate the cycle. That had the kind of critical insight into the kinds of realities that distinguish his first, and greatest, film, “Boyz N the Hood” (1991). (Singleton is also the producer of the current drama “Hustle & Flow,” a more ambitious and insightful urban film that also uses the talents of Terrence Howard and Taraji P. Henson.) “Four Brothers” wants basically to be an entertainment, although it deliberately makes the point that in an increasingly diverse society, people of different races may belong to the same family.

“Four Brothers” works as an urban thriller, if not precisely as a model of logic. There is, for example, a bloody and extended gun battle involving hundreds of rounds of machine-gun bullets and a stack of dead bodies, and afterwards a cop observes “it looks like self-defense.” Yes, but since that cop cannot make the point after the smoke clears, why is there no investigation to tidy up the carnage? I guess I shouldn’t ask questions like that in a Western, urban or otherwise; bad guys exist to get shot and good guys exist to shoot them, with a few key exceptions to keep things interesting. If you want to know how it all turned out, you need to get a transfer to the courtroom genre.