The argument could be made that all national borders are arbitrary. People have fought over them, and people have died for them, but—who made them? The power to concoct a line that keeps some inside and others outside is rare and rarified, and the inclusion vs. exclusion that is established by that geography has in turn shaped the world. A country can be a home, and a home can be erased, and the aching, lovely “Flee” trafficks in the space between belonging and wandering.

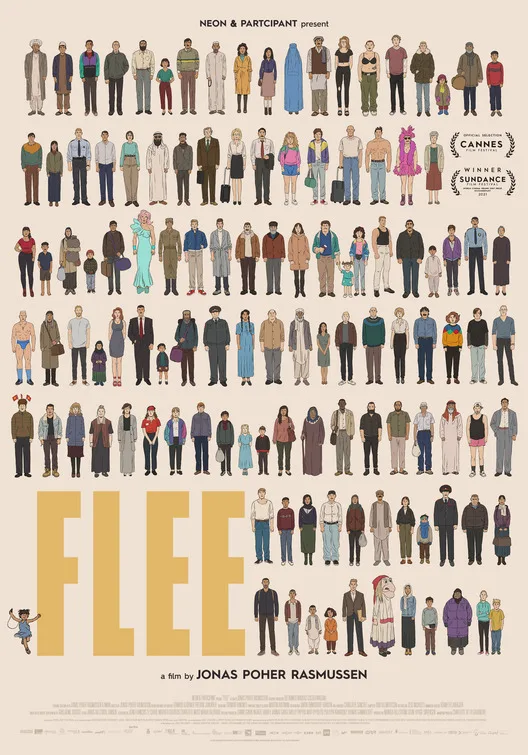

Evocatively animated in a style that is visually sparse but emotionally vibrant, with a strong sense of motion and interiority, “Flee” is written and directed by filmmaker Jonas Poher Rasmussen. As a teen growing up in Copenhagen, Denmark, Rasmussen became friends with a similarly aged Afghan refugee named Amin. Amin had fled Afghanistan after the Mujahideen grew more powerful during the First Afghan Civil War of the 1980s and 1990s, and arrived in Copenhagen alone. The two became friends, staying in touch as Rasmussen pursued filmmaking and as Amin pursued his doctoral degree. When they reconnect for the documentary “Flee,” it’s as adults ready to look back upon the past with a mixture of honesty, wistfulness, and resignation (from Amin) and curiosity and patience (Rasmussen). “This is a true story,” an intertitle states at the beginning, and the film honors the weight of that statement with an engrossing story that is as unflinching as it is—through a tremendous amount of human will—hopeful.

“Flee”‘s setup is straightforward, with Rasmussen guiding Amin forward in conversation, but the approach is never simplistic. The men’s friendship and familiarity with each other allows for a level of intimate expression that gives the film its simultaneous specificity and approachability. Scraps of memories are sometimes all we have of the people we loved and lost, and Amin compiles them together to speak about his deep bond with his family, his struggle to reconcile his sexuality with his conservative cultural background, and the trauma of being stateless. Each of his accounts starts the same way, with an animated version of Amin—brown-skinned, close-shaved, with a beard, a gold chain, and a world-weary look—laying down on a couch, staring ahead, and gazing directly toward us. That perspective of Amin looking up and us looking down creates a balance in which we’re an active participant, and as Amin slides into memory and transforms into a younger version of himself, we go too. (There are many reasons to pair “Flee” with this year’s other refugee-focused film “Limbo,” and their shared experimentation with the liminal quality of time is a primary one.)

Back to Afghanistan, where Amin’s happy childhood (flying kites with one of his brothers, spending time in the kitchen with his mother) is upended by civil war and by his father’s disappearance after being taken by the Mujahideen. The outlines of grey collapsing buildings and beige running civilians shift and melt while resistance fighters appear as solidly black, scratchily-shaded-in forms, both in contrast to Amin’s brightly dressed relatives and cozily decorated family home. To Russia, where Amin spent dreary, tedious years as a teenager: The color palette desaturated, the movement in these characters diminished, their facial expressions dampened. Back to present-day Copenhagen, where Amin’s boyfriend Kasper hits the walls and boundaries Amin has built around himself. And, slowly, to another version of Amin’s past that Rasmussen, through gently guiding questions, steadily unravels. “I just need to get one thing straight,” Rasmussen asks, and the pause he takes in between that statement and his following query is a whole world of poised possibility.

Where “Flee” then goes reveals a number of bleak truths about the gap between the “first” and “third” worlds and about the desperate measures people will risk for the chance at a “better” life. Refreshingly, “Flee” also makes space to consider what “better” means and by whose standards we assign that designation. What does living one’s truth matter if we’re all alone in the process? What vulnerability can we choose to allow ourselves, and what grace? A number of animated standout scenes drive these ideas home: a harried walk through a forest, its trees so tall they infringe upon the night sky; a claustrophobic, vertigo-inducing scene in a container truck, our perspective spinning around to survey the tight quarters; a meeting between a boat of refugees and a boat of tourists that is harrowing and heartbreaking in the contrasting expressions on these people’s faces. When “Flee” slips from animation to live action, it’s Rasmussen’s reminder of the reality of this story, and when he includes the arguments between himself and Amin about the direction of the documentary, that’s reality, too.

“We miscommunicate,” Amin says of a conversation he had in his adolescence with an Iranian man speaking Farsi while he, an Afghan, spoke Dari, but that statement is broader than two people and two languages. What are all the ways we fail to, or refuse to, understand another person? How does that decay into violence, into dehumanization, into negligence, into war? And when those gaps are fixed, what joy, what acceptance, and what love can be found? “Flee” asks those questions and then listens to their answers with open ears, open eyes, and an open heart, and the documentary is one of this year’s best.

Now playing in select theaters, with an expansion planned in January 2022.